How to live your best life: ideas from history’s greatest philosophers, from Socrates and Aristotle to René Descartes, Jean-Paul Sartre and Lao Tzu

- Modern philosopher Peter Cave explains the arguments of seven of history’s most famous and sheds light on their ideas for living life to the full

- Lao Tzu accepted that what will be will be; Aristotle urged to find a ‘happy mean’; while Schopenhauer believed that we should rid ourselves of desires

Philosophy is often thought of as being detached from “real life”. The greatest philosophers, though, sought to grasp the nature of human beings and their place in the universe, and gave guidance on how best to live one’s life to the fullest.

In his 2023 book How to Think Like a Philosopher: Scholars, Dreamers and Sages Who Can Teach Us How to Live, modern philosopher Peter Cave sets out the key arguments of the major philosophers, as well as those of thinkers such as writer Samuel Beckett.

Cave – who is based in London in the UK and read philosophy at University College London and King’s College Cambridge – shows what we can learn from their theories, and also from some quirky details about their lives.

Cave spoke with the Post about some of the philosophers he writes about in his book.

Want to help others and yourself? The mental health benefits of volunteering

1. Lao Tzu (born circa 6th century BC)

A Chinese master philosopher and the father of Taoism, Lao Tzu seems to accept that the reason for our existence will forever remain a mystery and we should not expect to find the answers to life’s big questions. This is a form of “quietism”, an acceptance of the way that things are.

Cave believes this is useful – to a point.

“To live well, we need to resist deceiving ourselves that all is clear or that ultimately all can be clear,” he says. “But although what will be will be, that does not mean that what will be must be. It does not mean that what we do will make no difference. We need to avoid being in denial of our responsibilities.”

There is doubt, however, that Lao Tzu was a real person. The most famous work attributed to him – the esoteric Tao Te Ching, a key text in the Taoist religion – is quite possibly a collection of insights by many thinkers, credited to a single author for cultural and political reasons at the time.

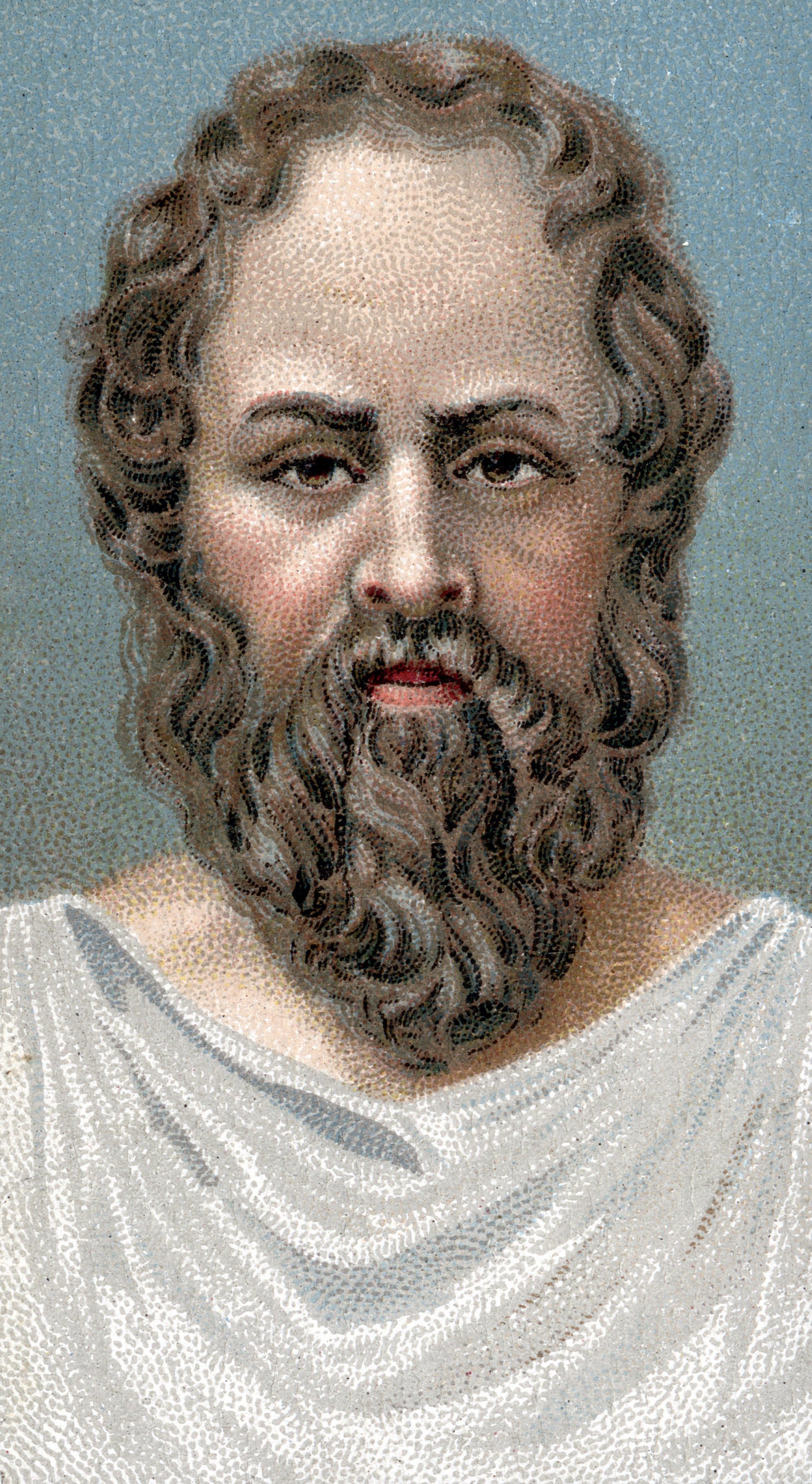

2. Socrates (469BC-399BC)

Socrates never wrote a word – his ideas were written down by Plato, who is himself one of the greatest of all the Western philosophers.

Socrates used careful and systematic face-to-face questioning to bring out inconsistencies in people’s thinking, with the aim of arriving at the truth. He often challenged widely held assumptions, and his legacy underscores the significance of critical thinking, as well as the pursuit of self-awareness.

“Socrates famously said that the unexamined life is not worth living,” Cave says. “Socrates’ urgings are in line with the fact that we human beings do reflect on our lives, on how to flourish and how we ought to live – although that doesn’t mean that we should always be reflecting.”

Socrates chose to die rather than renege on his principles. He was convicted of impiety and corrupting the young, and ordered to kill himself by ingesting hemlock, a poisonous plant.

He was given the chance to suggest an alternative sentence, but felt his beliefs obliged him to abide by the court’s lawful decision.

“Socratic questioning ended up with Socrates being condemned to death,” Cave says. “That wasn’t so bad for Socrates – he viewed death as finally freeing him from the distractions of biology, of desires for sex, food and status. He could then reflect on abstract forms of truth, beauty and justice unencumbered.”

3. Aristotle (384BC-322BC)

Aristotle was also one of the most influential Western philosophers and his inquiries spanned many fields.

Aristotle brought philosophy down to earth by emphasising the practical over the “abstract true reality” that beguiled Plato.

“Socrates was caricatured by the playwright Aristophanes as ‘having his head in the clouds’ – and that image has been much applied to philosophers,” Cave says. “The philosopher most associated with this is Plato, who is rightly considered to be one of the very greatest of philosophers. Aristotle was a devoted admirer of Plato, but brought Plato down to earth.”

Aristotle urges us to navigate life’s uncertainties by finding a “happy mean” – that is, embracing compromise and recognising that our values are matters of degree and depend on context.

“We have to live in the physical and psychological world of compromise, unclarities and conflicts. Aristotle recognises those features,” Cave says.

Aristotle’s insights encourage us to “muddle through” life’s complexities, Cave adds.

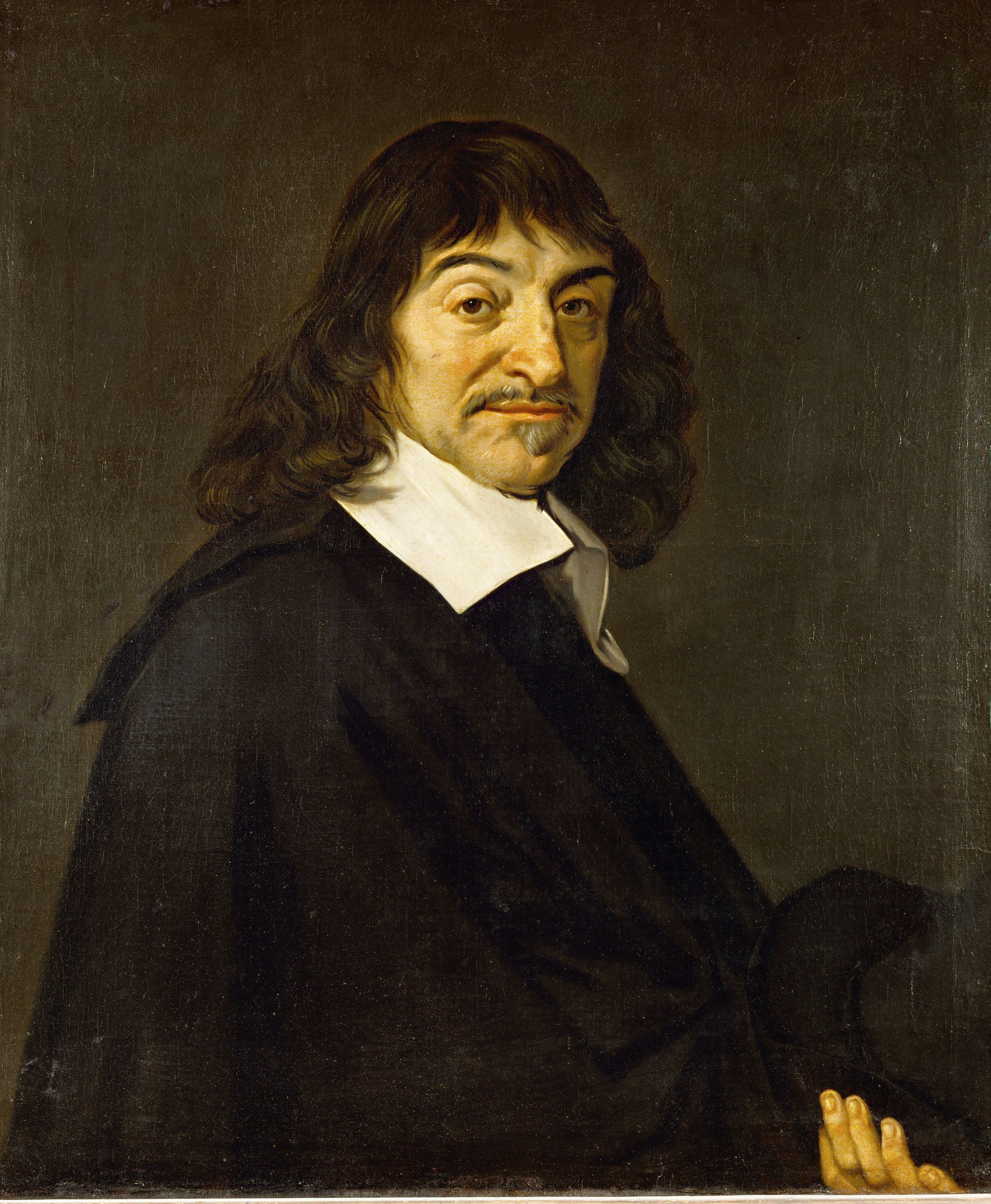

4. René Descartes (1596-1650)

Descartes thought that life’s mysteries could be solved by rational thought.

“Descartes is seeking to prove that the world around us can be understood through our reasoning, through mathematics – for our senses often mislead us,” Cave says.

Descartes achieved this via his “Method of Doubt”, a mind game in which he must doubt that everything exists until he can prove otherwise.

When he was engaging in the doubting, he realised that some entity must exist to be doing that doubting – it couldn’t occur on its own. This led to the famous “cogito”, his conclusion that “I think, therefore I am.”

Descartes believed that reason could help us make good choices and decisions, and live a life free of error. He argues, as Cave puts it, that proper reasoning leads us to see that even amid the saddest disasters and most bitter pains, we can always be content.

“We should grasp, for example, that contentment can be achieved by not dwelling on disasters, by not seeking what cannot be obtained,” Cave adds.

Descartes’ “cogito” led him to see that mind and body are distinct – this is known as “Cartesian Dualism”. A person is essentially a mind, but connected to their body during their lifetime. How this works has plagued philosophers and psychologists ever since.

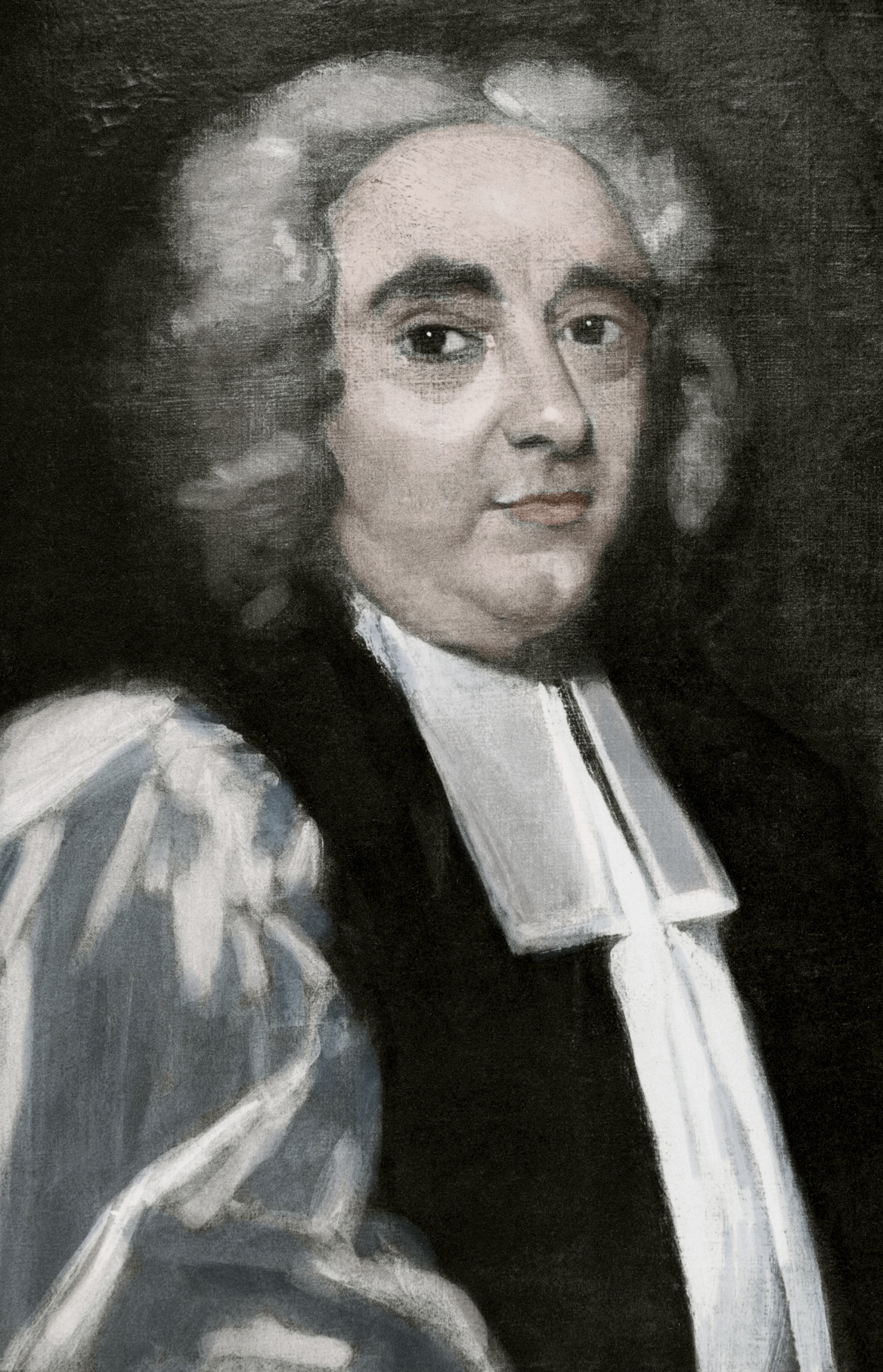

5. Bishop Berkeley (1685-1753)

George Berkeley, also known as Bishop Berkeley or the Bishop of Cloyne, was an Anglo-Irish philosopher. He asked us to consider the role of our sense perceptions in the way we shape reality. His proposition, “to be is to be perceived”, forces us to reflect on our own experiences.

Berkeley questioned whether the world actually exists outside ourselves, as all that we can be sure of is that we have sense perceptions. What if those sense perceptions are simply hallucinations, and there is nothing – no tables, chairs, cars, houses and hills – behind them?

Everything that we know about the world rests on our perceptions, Berkeley argues, and our perceptions might be the only things that exist.

“We have sensations of touch, sounds, sights, smells and so forth. Nothing can exist without our perceiving ‘it’- and so ‘it’ is nothing but our perceptions,” Cave says of how the argument goes.

If Berkeley is right, it would mean that if no one is seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling or touching an object, it would cease to exist until someone turned up and sensed it. It would simply disappear until that happened.

Berkeley, who was a Christian bishop, explained that odd situation by saying that an omnipresent god is always there to perceive everything – so things don’t actually disappear when we turn our backs on them.

Berkeley’s “god argument” has never sat well with other philosophers. But he did teach us to take our own experiences of the world seriously.

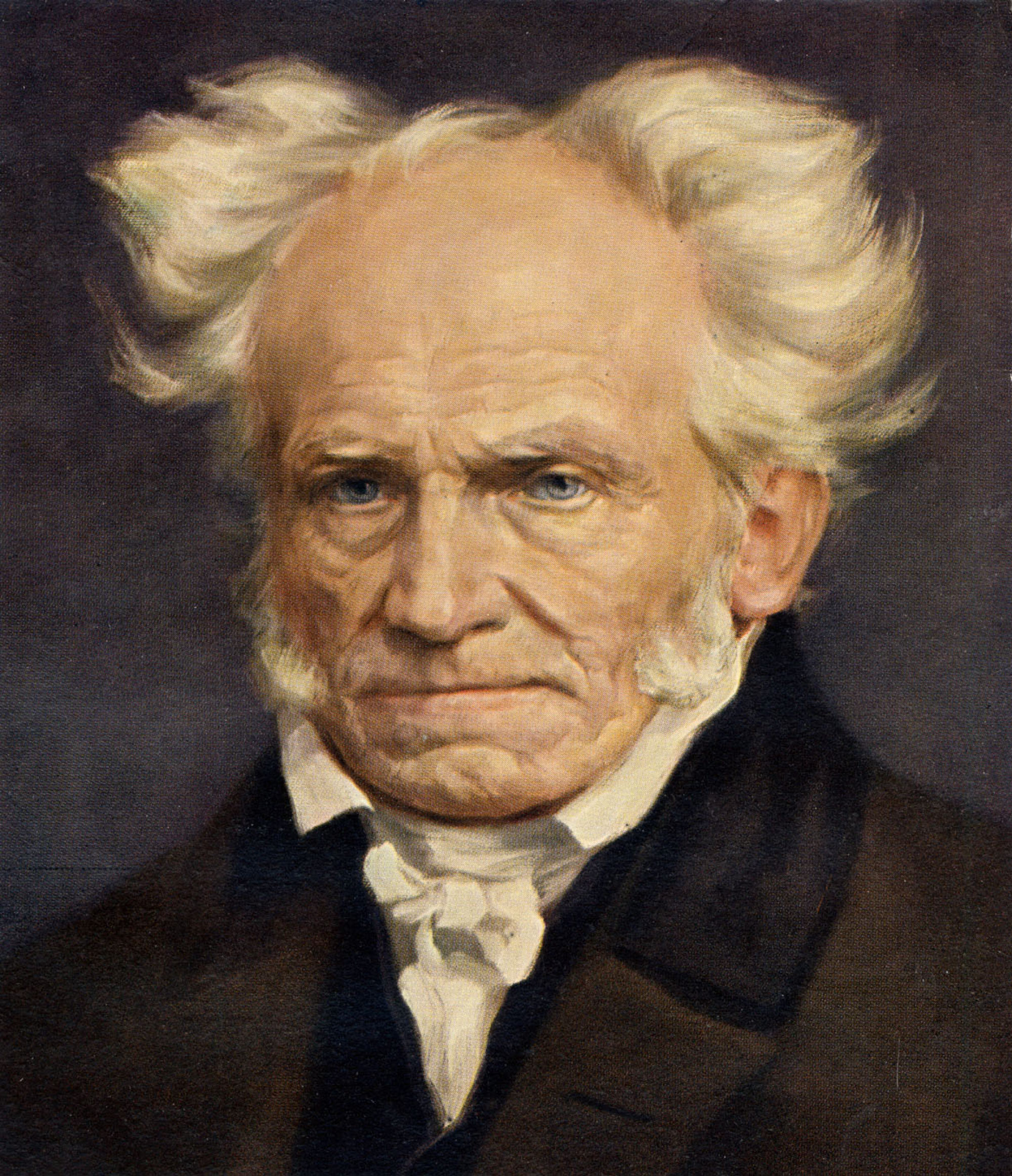

6. Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860)

Schopenhauer is often called a pessimist. He felt that life was irrational – a meaningless struggle in which the best we can do is minimise our pain by limiting our desires.

“There is the constant urging to have aspirations, to compete and acquire more than others – be it to acquire bigger cars, more exotic holidays or higher status,” Cave says of Schopenhauer’s ideas.

“We desire to achieve things – and while doing so we are suffering, for we don’t yet have what we are trying to secure. But then either we fail, and so [experience] the resultant suffering of disappointment, or we succeed, and hence boredom steps in and we set off trying to achieve something else – and so, more suffering.”

Is there any escape from this pain in Schopenhauer’s philosophy?

“He pointed out how we can sometimes lose ourselves – lose the will, the self – in the arts, particularly in music,” Cave says, noting that he endorses that position himself.

7. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980)

At the heart of Sartre’s existentialist philosophy is the idea that we have the capacity to invent ourselves.

Sartre said that there is “nothingness” at our core, and we are therefore free to choose how to interpret and develop our lives.

“Many items have been built with a purpose or function or essence in mind – the inkwell, the staircase, the bottle opener,” Cave says.

“Aristotle wrote of natural items having different functions. The one clarity to be found in Sartre is that you and I are so very different from items with a function. A ‘nothingness’ is our being, in that we are free to choose.”

What to do with that freedom is a problem we must all struggle with, Cave notes.