Breast cancer survivor on folly of ‘Asian way’ of hiding illnesses after aunts failed to share own diagnoses

- Kim Li was furious none of her father’s sisters shared an important detail of her family’s medical history that could have spared her much suffering

- She says hiding your illness because of shame might be the Asian way, but it could mean a missed opportunity to save a loved one

On a sunny afternoon in October last year, Hong Kong-born Kim Li could not have anticipated how her world would be turned upside down when her 14-year-old daughter Priya came home from school in tears, having discovered her school friend had just found a lump in her breast.

Li, a former science teacher at Hong Kong’s King George V School who was now teaching at Northampton High School in the UK, was used to dealing with teenage upsets. But as she tried to comfort her daughter, Li couldn’t shake the nagging worry about the lump in her own breast, which she had been ignoring for over a month.

That same evening while chatting in bed, Li asked her physician husband Bharath Lakkappa to feel the lump. She knew he would put her mind at ease if he said it was nothing. After he felt it, however, her husband became quiet. He turned off the light and said: “We need to ring the GP tomorrow.”

The following morning the doctor made a referral for Li to see a specialist, and on November 13 she went to the breast screening department at Northampton Hospital. Within minutes of his examination the specialist said he was “highly suspicious” and Li was sent to have a mammogram and breast ultrasound, where a biopsy was taken.

“I remember lying on the hospital bed, staring at the dark blob as the radiographer rolled the scanner over my breast to measure the size of my lump. It was big and alien-looking. Every muscle in my body was tense and I was filled with dread.”

Li was crushed, knowing she wouldn’t be able to return to work or have a normal life for the next six months, and the fear of what might come after was too much to bear.

“I burst into tears once we got into the car, though I tried to stay stoic for the sake of my family. I wasn’t ready to die, wanting to see my children graduate, get their first jobs, get married and have children. I felt angry that cancer had chosen me and felt life was horribly unfair.”

Li considered her family to be close and broke the news to her parents and siblings together. She wanted to include them in her fight against cancer so they wouldn’t be scared in case it ever happened to them or someone they knew.

It was then that Li got the biggest shock of all: three of her father’s sisters had been diagnosed and treated for breast cancer. But because of their conservative Asian upbringing, where illness is often associated with shame, none of them had shared this information with the family.

“I learned far too late that I had the BRCA1 gene [one of two major genes linked to breast cancer risk] on my paternal side. I was furious that none of my aunts had shared this important detail of our family’s medical history,” Li says.

“Being a scientist and having a physician husband, I would have been far more vigilant in regular screening as the genetic risk of cancer is much higher when two members from the family have it, and early detection is key for a high survival rate.”

Li was especially upset with her cousin, who is a nurse and chose to have a double mastectomy despite screening negative for the gene, but kept this information to herself. It didn’t occur to her that Li’s side of the family was just as much at risk as her.

“This is a massive misconception about cancer – that only girls can carry and pass down the gene. In my case, my father was the carrier and unknowingly passed it on to me. My poor dad felt so guilty and ashamed that he hadn’t somehow protected me. Of course I didn’t blame him. Just like me, he didn’t know we carried the gene.

“Chinese people and Asians in general, especially the older generation, don’t like sharing [about] illnesses or bad news because it is associated with bad luck and shame,” Li adds. “But they don’t realise that by sharing, we can be more aware and possibly save lives. I’m not blaming them for having outdated views. They haven’t had our education. But for their own sake, we need to help them understand.”

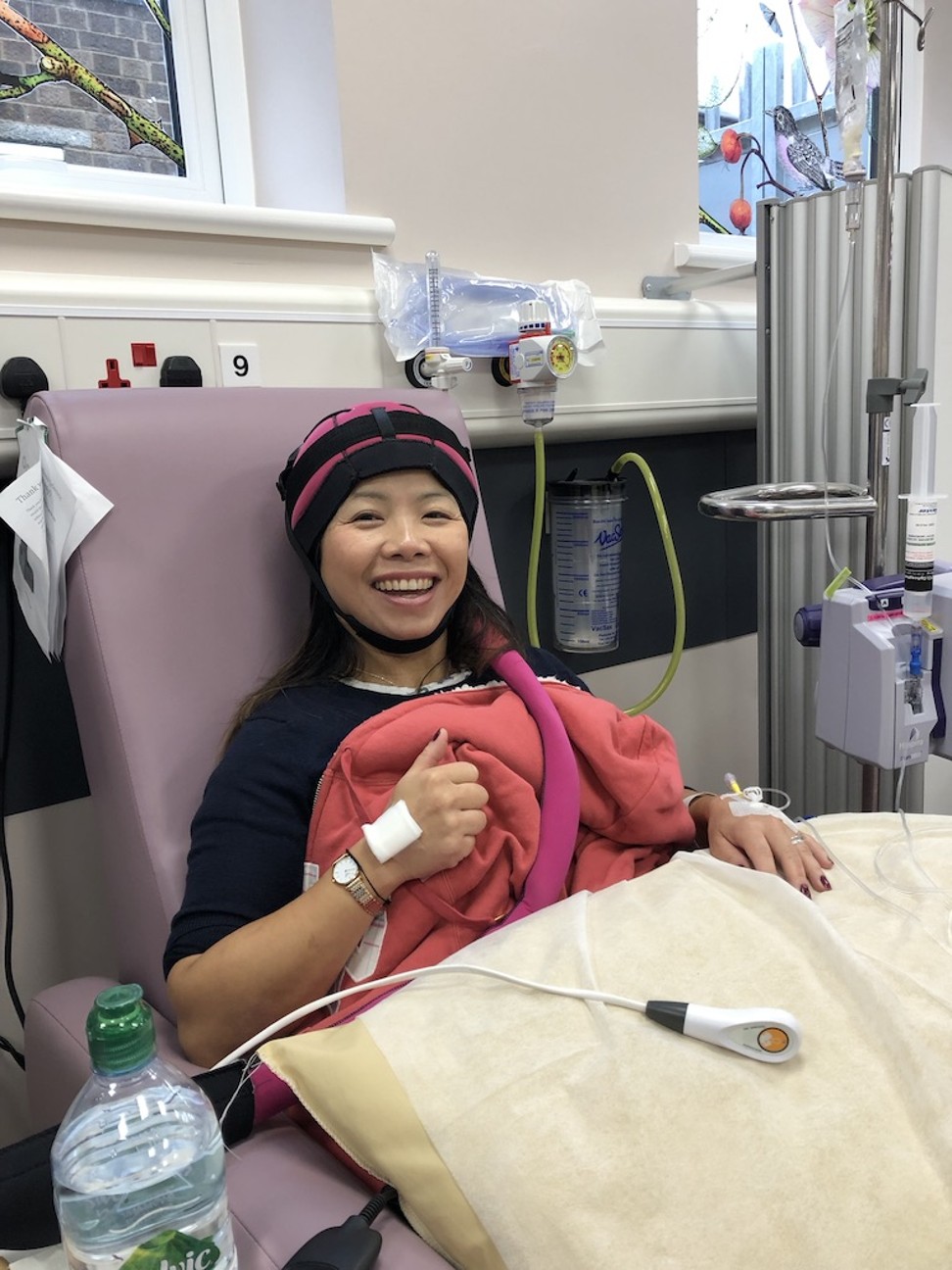

Li was determined to make her journey through chemotherapy and the double mastectomy as public as possible on social media so that she could help others and raise awareness of breast cancer. She shared the highs and vulnerable lows with a supportive community that has grown around her on a public Facebook page.

More than anything, people need to know that cancer doesn’t have to equal death if you’re vigilant with screening. Catch it early and act fast

Her support group joined her in mourning the loss of her beautiful hair and watching her nails go black, and encouraged her when she was no longer able to taste food. They helped her endure months of excruciating pain, having to resign from her teaching job and, after her double mastectomy, the dread of waking up to the ugly scar across her chest each morning.

“The impact on my family was traumatic,” Li says. “Bharath watched me transform from a happy wife to depressed zombie, and the saddest part for him was that despite being a doctor, there was nothing he could do to ease my pain and suffering. Our children also had to grow up far too quickly, bearing heavy responsibilities and heartache. It was especially difficult for my son Krishna, who was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes on top of everything else.”

On May 16, Li was preparing herself to begin radiotherapy treatment. Instead, she was given miraculous news: the biopsy results from the breast tissues and lymph nodes taken during her operation had come back negative. She was told she didn’t need further treatment and could go home.

“I was euphoric. It was the best feeling ever. I was free. Bharath’s face lit up and that sense of relief was just incredible. We had been given a second chance.”

Through Li’s episode, her parents have opened up about their feelings and adopted a healthier, more empathetic approach towards the ill. Before, they judged cancer patients as those who ate too many preservatives or lacked exercise. Sadly, this type of stereotyping is still common among Asian families today.

Now in remission and after being given the all clear, Li continues to use her situation to help others. She raised money for Macmillan Cancer Support by taking part in a 26-mile hike across Britain’s Wye Valley with a group of keen supporters, which took place on September 6.

“I was grateful to the Macmillan nurse who looked after me when I lost all my hair,” Li says. “They gave me a free wig and provided a free make-up workshop to regain my confidence and self-esteem. We’ve raised over £10,000 [US$12,500] so far and continue to welcome contributions through [the website JustGiving].”

As luck would have it, Priya’s school friend’s lump was found to be benign and has since been removed. Had she not discovered it, however, and had Priya not been so distressed about it on that sunny day in October, Li might not be alive today.

Li’s message after surviving cancer is that hiding your illness, especially from relatives, might be the Asian way, but it could mean a missed opportunity to help a loved one. She also believes that knowing what predisposed genes you have can save your life.

“More than anything, people need to know that cancer doesn’t have to equal death if you’re vigilant with screening. Catch it early and act fast.”