Photo Kathmandu adopts an artistic approach to Nepal’s post-conflict, earthquake revival

Exhibitions are hoped to show the country in a new light

Photos of the mighty Himalayas and mythical temples and monasteries that dot the once forbidden kingdom have long encouraged thousands of thrill-seeking and soul-searching tourists to make a pilgrimage to Nepal. When the country opened to tourists in the 1950s, early photographers documented everything from mountains and mountaineers to Hindu monks and Western hippies mingling euphorically during the height of Kathmandu’s hippie days in the 1960s.

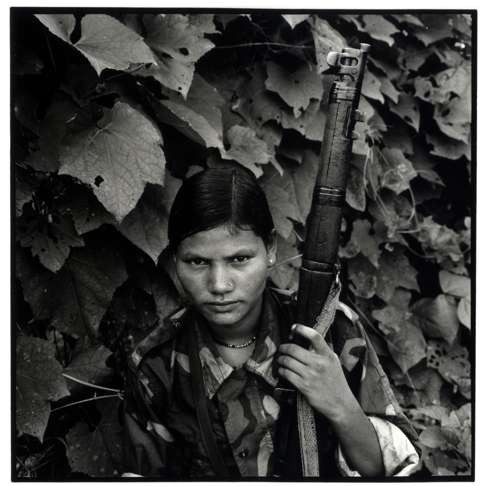

In later decades, photos of the armed conflict between the government and Maoist guerrillas contrasted with pictures that imagined Nepal as a Shangri-La-like destination.

But amid the rubble, a group of young Nepalis including Nayantara Gurung Kakshapati aim to reconstruct Nepal’s image using the same medium that showed the disastrous aftermath of Nepal’s biggest tragedies since the 1934 earthquake.

The event was planned before the quake, she says, but was later focused to help put Nepal back on the tourist map.