Profile | ‘I have two brains’: Hong Kong artist Eddie Lui on his rational and sensual sides, his struggles in the city, and dealing with angry triads

- An ex-banker who held his first solo art exhibition in 1973, Eddie Lui Fung-ngar spent two years bedridden as a child after a herbalist dislocated his hip joint

- As a planning director for the Hong Kong Jockey Club he oversaw the conversion of a nine-storey industrial building into the city’s first artist studio centre

My father was from a humble peasant family and my mother from a wealthy family. Her parents weren’t happy about the marriage.

They moved to Hong Kong in the 1940s, the first generation of immigrants from Haifeng county, in Guangdong province, and settled in Sam Sup Kan, which translates as 30 houses and was directly behind what is now PMQ, in Central.

Legend has it that a rich man built the houses to accommodate the new arrivals, but it was overrun in a short time and more tong lau (tenements) were built.

My father set up a teahouse on Kwong Hon Terrace serving the coolies and rickshaw pullers. I was born in Hong Kong in 1947 and had a brother who was 12 years my senior. When I was two years old, my father contracted tuberculosis, and we moved to my parents’ hometown, a poor and backward fishing village.

Quack remedy

My father died a couple of years after we moved to China. My mother’s family was no longer rich, the Communists had confiscated everything, even our papers, and they took over the big family house and gave us a small hut to live in.

One rainy day I hurt my ankle and my mother took me to a herbalist who did a painful manipulation and dislocated my hip joint, which meant that my femur bone started growing outside the socket. I was bedridden for two years with the inflammation. I couldn’t walk and had to be carried around.

My mother persuaded the Communists to let her search the warehouse where they stored the confiscated goods and look for my birth certificate. She found it, proving that I was born in Hong Kong, and they agreed to let her take me to Canton. We stayed there for nine months and in 1956 she managed to buy our way out.

One angry man

My brother was already in Hong Kong and in a joint venture with an uncle running a small rice shop on Ma Tau Wai Road, in Hung Hom. I went to a private primary school on a rooftop in Hung Hom. There was a cement factory nearby and it was a dusty and smoky area.

I was several years older than the other students and walked with a bad limp, with one hand on my knee to support myself. One day, walking to school, I came across an angry man who was annoyed with me for being in his way and he punched me in the stomach.

‘Being Chinese is so important’: how bullies helped him embrace his culture

From that day on, I walked with a less obvious limp, that was how I began my Hong Kong struggle. As I grew, my right leg became longer and my left leg was dangling, shorter than the other. Because of my condition, I usually sat out of sports lessons, but my reward was that I became a silent observer and came to see the world in great detail.

Discovering art

I was fortunate enough to be accepted into Hung Hom Government Primary School, it cost HK$5 a month. It was a new school and the facilities were first class, with an art room and a carpentry room, and there was a portrait of Queen Elizabeth in all the classrooms.

It was there that I discovered my talent for drawing. Whenever there was a celebration in the school, they always asked me to do a drawing. My mother didn’t want me to become an artist, she thought I’d starve, and told me to focus on my regular subjects.

We were allocated a housing unit in So Uk Estate, in Sham Shui Po. My brother quit the rice shop and became a policeman and my mother took over the shop, but because of the debt she inherited with it she was thrown into jail for about a year.

When I was 12, I was accepted at the Moral Training English College, in Kowloon Tong, where the teachers were expats and most of the classes were in English.

Night classes

When I was 20, I met Patsy in a youth group at Caritas Creative Art Centre, and we got married the following year and had two sons. Through my brother’s introduction, I got a job as a book-keeper in a local family-run bank, Liu Chong Hing Bank, in 1968.

I was really interested in becoming an artist and was doing a lot of life drawings. I applied to the art and design programme offered by the Department of Extra-Mural Studies at Hong Kong University; it was the only proper visual arts training in Hong Kong at the time.

It was a well-designed, three-year certificate course – we learned everything from ink and brush painting to sculpture and ceramics. We had excellent teachers including the sculptor Cheung Yee and architect Tao Ho.

It was an evening school. I’d leave the bank just after 5pm and get to class at 6pm with a bowl of noodles in my stomach. The classes ran until 10pm five nights a week; it was a challenge to do it with a full-time job. It was good training in time management.

Take it to the bank

Before I finished the course, I had my first solo exhibition, in 1973, at the Goethe-Institut, under the aegis of the Hong Kong Arts Centre. I am now recognised as one of the early artists to engage in what the art world normally refers to as contemporary ink painting in Hong Kong.

I consider myself fortunate to have been raised at a meeting point between East and West. Nigel Cameron, a South China Morning Post art critic, bought two of my paintings and wrote a very flattering article about me, which helped boost my career.

In my first exhibition I sold four pieces, which was worth more than my banking clerk’s salary. I was overjoyed, but it didn’t last long because there was no market for art.

It so happened that retail banking was on the way up. I moved to electronic data processing and then joined Grindlays Dao Heng Bank. I joined as a systems analyst and was then made the consumer operations manager because of my systematic approach in running a unit. My banking career began to flourish.

I was the first Chinese manager mandated to come up with a set of operating procedures and responsible for the implementation of the Consumer Banking Operations Manual, a bilingual manual in seven volumes.

To Calgary and back

In 1989, worried about the return of Hong Kong to China, I moved to Calgary, Canada, with my wife and young children. Calgary was peaceful, we had a huge bungalow, a long driveway and a big basement that served as my studio. I started an art business, selling my collection. It barely paid the rent.

I was introduced to a shop space by Winnie Mak. She was a big-shot realtor who was very interested in visual arts and had learned painting from ex-Hong Kong artists in Calgary. We had a common language.

A headhunter approached me for a risk management job, and I was relocated back to Hong Kong at the end of 1992. I lived with my mum, who was very ill at the time; I’m glad I got to have those 18 months with her before she passed away.

By that time, I’d divorced. Winnie had moved to Hong Kong and we married. I was managing the bad loans of a couple of banks; it was a couple of scary years for me because the debtors could get very angry, some were triads. In 1995, I quit banking entirely.

Winnie was interested in art and I was also fully devoted to art; the next stop was full-time art making. We began to look for jobs with the Arts Development Council (ADC) as a consultant. The first paper I wrote for ADC was “Survival Training for the Visual Artist”.

Later on, I taught survival training – how to write an artist statement, do a portfolio presentation, get funding, deal with galleries and a legal framework – to students at Chinese University’s Fine Arts Department for a couple of semesters.

The man with two brains

From 1995 onwards, Winnie and I ran art classes for kids in North Point. We were doing pretty well and then moved to Golden Dragon Industrial Centre (in Kwai Fong) and set up a studio.

I have two brains – one is more rational, for computers and business administration, and the other side, luckily, is focused on sensual and artistic things. I think it was this mix that got me the job as the planning director of the JCCAC (Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre). The position was to oversee the conversion of a nine-storey industrial building into Hong Kong’s first artist studio centre.

I ran the space for two years and when I had produced a balanced budget, I left and went into full-time art alongside Winnie. We share a studio. I’ve had regular exhibitions since 1988 and in the past five years have had one every year.

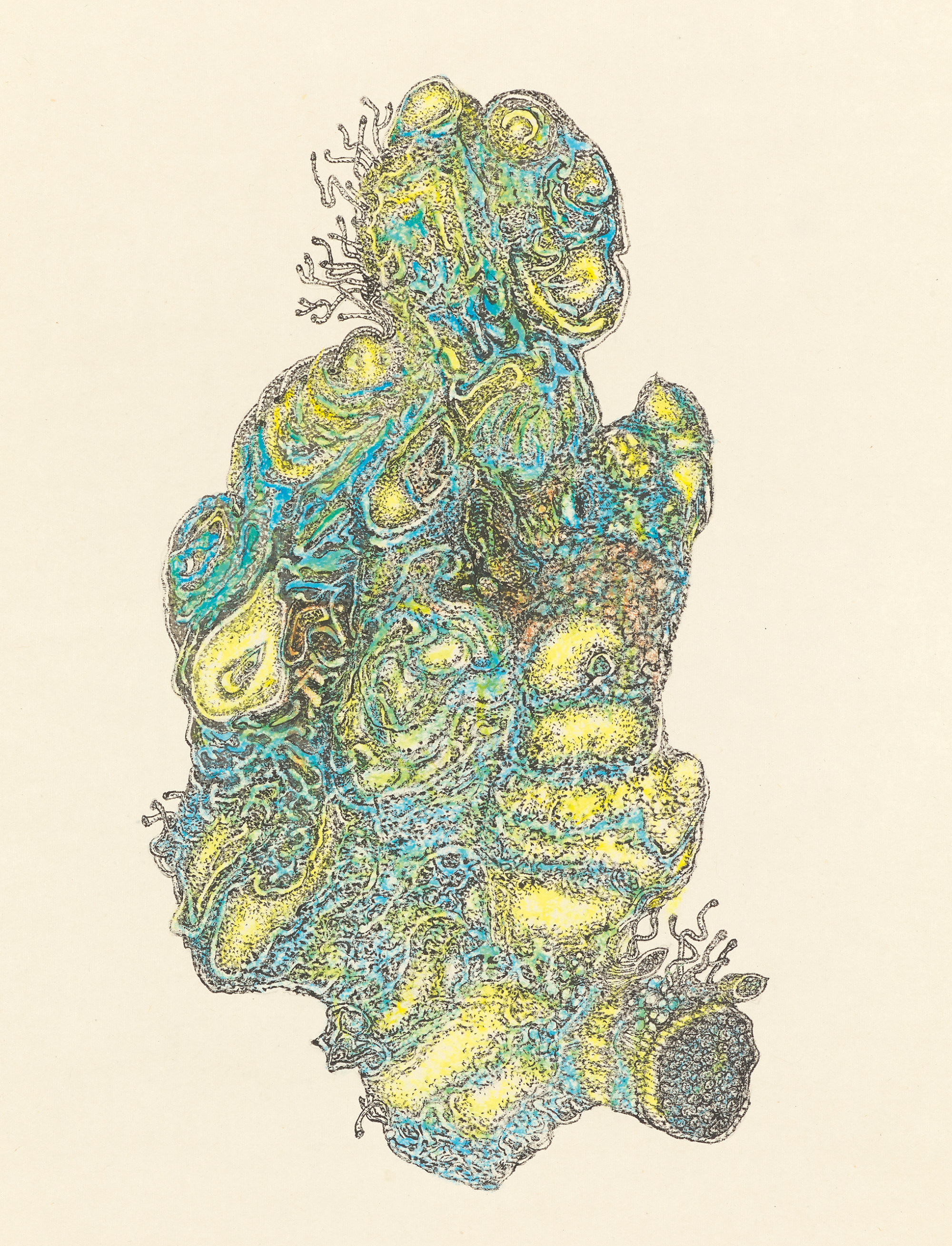

My most recent exhibition opened at the end of October in Taipei – I couldn’t make it because I’m recovering from an operation, the result of a fall last year (2021). When I was recovering, I was confined to a room and began drawing a lot of vegetables and fruits.

At the time I was thinking a lot about Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. I drew a piece of ginger, which has blues and yellows, and when you stand it up, it looks like a heroic President (Volodymyr) Zelensky. Ginger in Chinese herbal medicine is to get rid of a cold and keep your immunity strong, so I drew inspiration from there.

I always try to say something in my work. I never copy myself, never repeat my ideas.