Review | James Joyce-like novel about Japanese genocide of Taiwan tribes is a tough read, but worth the effort

Award-winning Remains of Life, written without chapters or paragraphs, is a technically daunting account of a terrible event from Taiwan’s occupation that has taken 18 years to publish in English, and it’s not hard to see why

by Wu He

Columbia University Press

It’s taken 18 years for Wu He’s critically lauded Remains of Life to appear in English translation, and a glance at the text readily explains this delay.

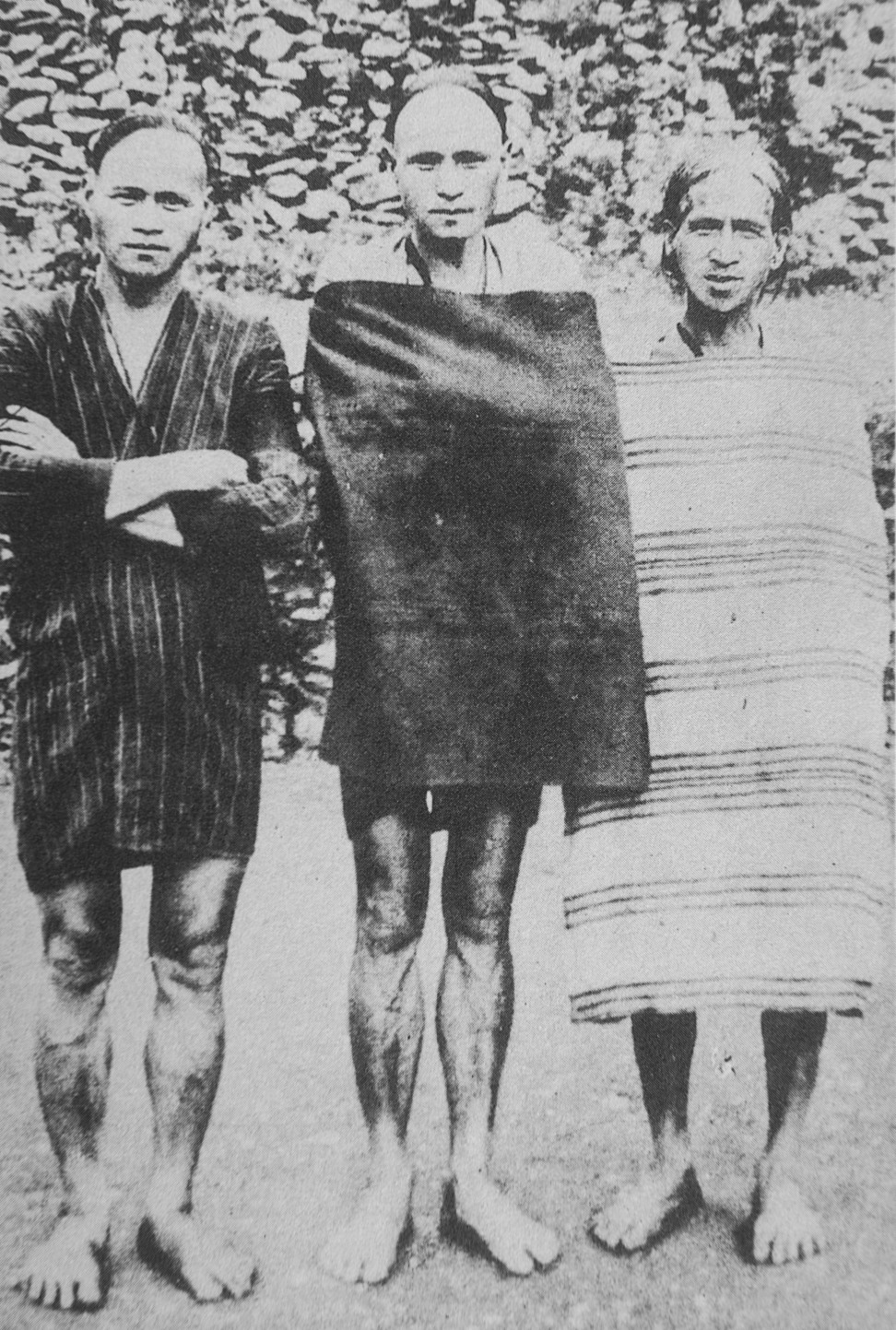

This is an avowedly experimental novel that revolves around one dreadful event. On October 27, 1930, at a sports meeting at Musha Elementary School, on an aboriginal reservation in the mountains of Taiwan, a bloody uprising took place against the Japanese. By noon, the headhunting ritual had left 134 of the occupiers decapitated. The colonial power’s response was to mobilise a 3,000-strong militia, roll out the heavy artillery, put planes in the air and deploy poisonous gas in a ferocious act of genocide that saw the near extermination of the Seediq tribes.

The Musha Incident, as it came to be known, had been forgotten by many Taiwanese, but the book led to a resurgence in interest, and a new evaluation of its significance.

Remains of Life has little concern for orderly narratives or neat conclusions: it has no chapters or paragraph breaks, and few full sentences. It combines a historical study of the Musha Incident, the Seediq and surviving tribe members (the “remains of life”), philosophical ruminations on time, the human condition, history, sexuality and violence, and sudden lurches into fantasy and even metafiction.

The book is also largely about Wu He’s writing of the novel, his stay in the reservation, his relations and interactions with surviving members of the tribe and his analysis of the incident.

This metafictional strategy allows the narrator/author to circle around the Incident, to fictionalise his experiences and reflections, rather than going for conventional fictional narrative or realistically (if artificially) documenting his experiences. One could almost call it gonzo, though the book has none of Hunter S. Thompson’s frenzied, bitter prose.

None of the radical, experimental techniques deployed by Wu He are unique, but as the reader is so strongly aware of them, they deserve consideration.

The most obvious is the endless stream of uninterrupted prose, with perhaps 20 sentences in the entire book. This has some antecedents: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) was famously written single-spaced and without paragraphs on a single 120-foot typewriter roll that he had glued together, the better to capture a spontaneity analogous to improvisational jazz. Scottish author James Kelman likewise has produced a number of short stories without paragraph breaks, in an attempt to convey the unrelenting quality of the protagonist’s misfortunes and misery. In both cases, the continuous prose conveys an inexorable energy or force.

Remains of Life is challenging but not unrewarding, and it is, of course, politically and historically important

This is less apparent in Remains of Life, which can veer from poetic to banal in a few short lines. At one point, we read “Old Daya thanked Young Wolf for his hard work taking care of the inn, he knew enough to preserve the original look of the first floor, the hot springs tubs on the second floor were all kept clean and the comforters were all properly folded neat and tidy”, but shortly afterwards are flabbergasted: “this was a time that many of the Mhebu mothers displayed the great courage of Atayal women, for some reason many of them hanged their children from the trees [and] throwing their children from the high cliffs as they passed by Valleystream”. Banality and horror coexist, as in life.

Wu He – “Dancing Crane” – is the pen name of Chen Guocheng, and his use of names is important. Characters have somewhat cartoonish or emblematic names, such as Girl, Nun, Deformo and Drifter. This technique, too, has been used elsewhere, from William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch (1959), the cast of which includes The Sailor and The Buyer, to Irvine Welsh, who helpfully names characters such things as Sick Boy and The Victim. Similarly, Taiwan is referred to as “island nation” and the Chinese as “People from the Plains”.

This makes the cast feel archetypal: Girl becomes representative of all women on the reservation, perhaps even of all womankind, and Taiwan emblematic of all islands dominated by “the mainland”. Though the details are intensely local, this technique attempts to universalise the lessons and details of the Incident. It doesn’t always work – what feels innate for someone Chinese does not always transfer outside of that mindset – but it’s a significant move by Wu He.

His ruminations are frequently superb – passionate, insightful and earthy. Consider this, on the dehumanising effects of colonisation on the indigenous tribes: “[…] in 1911 a war broke out resisting the Japanese order for tribesmen to turn over their rifles because rifles were the most prized possession for heroic hunters, how could they possibly hand them over because of some ‘political’ excuse the government came up with, this continued until the Japanese bombs ended up on their doorsteps and they finally unwillingly handed over their rifles, but ever since that time the tribal hunters’ ‘dignity’ suffered a terrible blow, the same year they also resisted the order to hand over their collections of human skulls, because they were important sacrificial objects in their rituals […] giving them up was like handing over their dignity, and once it was later forbidden to display their skull racks there wasn’t even a place to put their ‘dignity’ anymore, tattooing was prohibited in 1917 and the following year they started instituting short hair for men and outlawed the practice of otching, a tribal rite that disfigured the front teeth, after all of this that and the other the Japanese may as well have dictated the length of the tribespeople’s ass hair […]”. One does not have to look far to find modern equivalents, such as the ban on religious names and “abnormal” beards in Xinjiang.

Remains of Life is challenging but not unrewarding, and it is, of course, politically and historically important. While some literary techniques become mainstream, others remain experimental for a reason. The absence of chapters, paragraphs and sentences make Remains of Life a daunting tombstone.

Yet it has moments of solemn tragedy and deep pathos, of fiery passion and humane insight, which keep you turning the pages. Some may enjoy the disruptive effects of its style, or the tale of a man haunted by history, or Wu He’s attempts to remember a forgotten people and to understand dreadful events. Remains of Life has all that, and more.