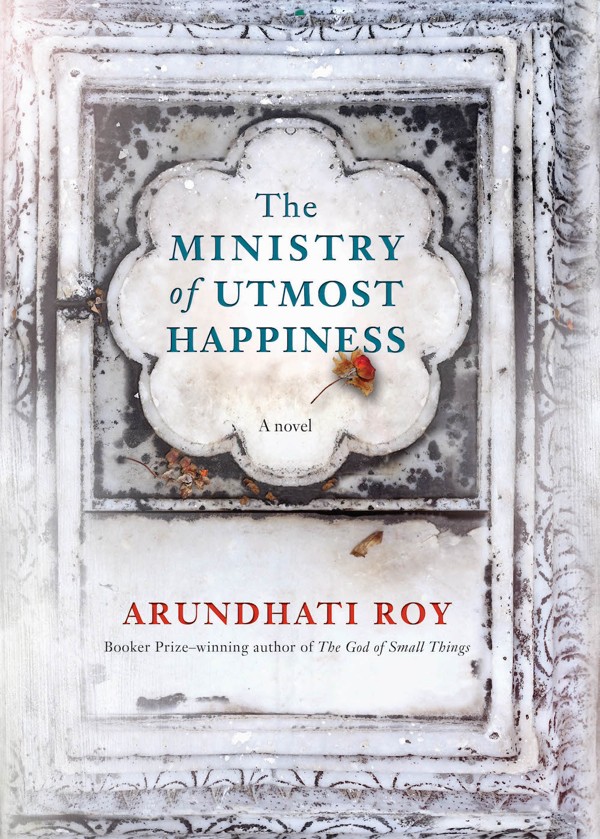

Review | Arundhati Roy’s first novel in 20 years, although not a complete success, shows she’s no one-hit wonder

The Booker Prize winner returns to fiction with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, a story of religious and political violence full of lush prose but spoiled in places by expository detail that becomes overwhelming

by Arundhati Roy

Hamish Hamilton

When India became independent in 1947 alongside newly created, Muslim-majority Pakistan, Saadat Hasan Manto, arguably the greatest South Asian writer of the 20th century, remarked that Indians and Pakistanis might be politically free, but they remained the “slave of prejudice … slave of religious fanaticism … slave of barbarity and inhumanity”.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, the first novel in two decades by celebrated Indian writer and political activist Arundhati Roy does plenty to suggest that, 70 years after the end of British colonial rule in India, Manto’s insight remains true.

Islamic extremism has all but torn Pakistan apart. In India, meanwhile, a growing list of atrocities against Muslims by supporters of the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) could be a blueprint for the horrors being inflicted on innocents by the Islamic State in its pursuit of a new caliphate.

Early on in Roy’s novel, her protagonist, Anjum, watches as the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York unfold on television. “Tiny people jumped out of the tall buildings and floated down like flecks of ash,” observes Roy in the omniscient voice with which she narrates most of the novel. “Even the dust looked different – clean and foreign.”

Anjum, who resides in the medieval walled city of Delhi, next to the Indian capital, is Muslim. It doesn’t help that she’s also a hermaphrodite – or a sexually impotent hijra, the Urdu word for women who feel trapped in a male body and who live on the margins of Indian society.

While travelling in Gujarat, Anjum finds herself caught in a pogrom of Muslims by the Organisation’s supporters. (The incident is based on the 2002 Gujarat riots, in which thousands were killed.) A mob looking for survivors among heaps of dead Muslims finds Anjum. Her life is spared – not as an act of mercy, but because her assailants believe killing hermaphrodites brings bad luck.

Grief-stricken, Anjum takes refuge in a desolate graveyard, where she gradually recovers with the help of friends. Roy, who likens Anjum to an ancient tree, describes her life in the graveyard in elegiac prose that characterises the novel’s first 100-odd pages, lending them a fairy-tale quality: “At dawn she saw the crows off and welcomed the bats home. At dusk she did the opposite. Between shifts she conferred with the ghosts of vultures that loomed in her high branches.”

It’s not long before Anjum transforms the graveyard into a sanctuary for social outcasts like herself. She even opens a funeral parlour, strictly for the downtrodden, who otherwise have nowhere to go for their last rites. Anjum, whose voice and idealism seem unmistakably to be Roy’s, calls the place Jannat Guest House and Funeral Services. Jannat, the Urdu word for “paradise”, is exactly what Anjum’s safe haven means to its guests.

The graveyard enterprise also explains the book’s somewhat surreal title: shared humanity – not economic growth and disposable incomes – is essential for there to be happiness. Unfortunately, the idea that social solidarity can bring happiness doesn’t become evident until much later in the story. To get there, the reader must struggle through several plot lines linked to an elusive, obstinate woman and three men who loved her in college.

S. Tilottama, nicknamed Tilo, and her admirers, including a Kashmiri militant named Musa, make their first appearance about a third of the way into Ministry. Suddenly the novel lurches into much more overtly political territory.

The reader is transported from the scorching plains of Delhi and Gujarat to the one-time Himalayan kingdom of Kashmir. One of India’s Mughal emperors famously described Kashmir as “paradise on Earth” – this at least partially explains why India and Pakistan claim the territory, which has been the focus of a separatist rebellion since 1989.

Tilo appears to be modelled on Roy. Like the author, she was raised by a single mother who was a teacher. Tilo is a social rebel and risk-taker who studied architecture in college in the 1980s – just like Roy.

These two storylines are so disparate they might have come from separate novels. Roy eventually merges them by bringing Tilo and Anjum together in the graveyard, which has expanded to include “a Noah’s Ark of injured animals”.

There, the two characters minister to each other while finding solace among a collection of social misfits, including a cross-dresser who has lost “her mind as well as her memory” but who knows everything there is to know about government schemes for minorities.

Moreover, Roy, who is something of a poster girl for Kashmir’s independence from both Indian and Pakistani rule, does not do enough to illuminate the Kashmir section of her novel.

Instead of focusing on her otherwise captivating characters, especially the long-running relationship between Tilo and Musa, Roy introduces the reader to Kashmir as a journalist might in a long, tedious magazine article. And the author zooms in on characters whose only purpose is to point to the brutality of India’s policies.

Roy’s 444-page novel may be ambitious and big-hearted, but it is also too long and lacking in clarity. And given the author’s approach, readers may find it a challenge to appreciate many of the story’s historical and cultural references.