Review | Richard Branson’s latest memoir reveals perhaps more than the Virgin emperor intended

A fun romp brimming with anecdotes from the eccentric British billionaire’s extraordinary life

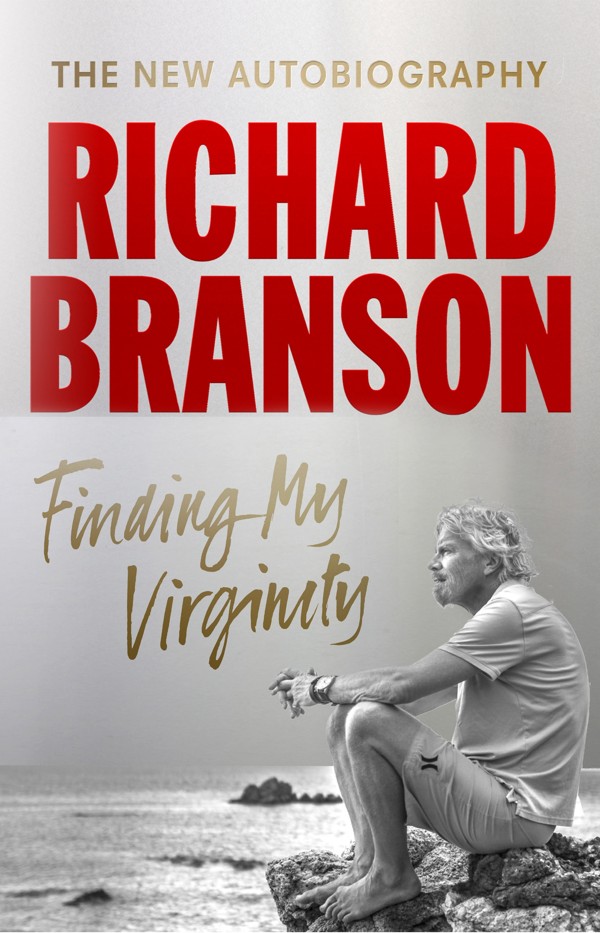

Finding My Virginity

by Richard Branson

Virgin Books

Some people have the good fortune to be high achievers in multiple fields. As well as being an extraordinary poet, Philip Larkin was a noted university librarian and a fine jazz and book reviewer. Great Britain’s wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, was a gifted oil painter and productive writer. Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates is perhaps this century’s most generous philanthropist.

This is understandable: some people are born with remarkable drive and intelligence, and apply those attributes to their various interests. In Richard Branson’s second volume of memoirs, Finding My Virginity, we learn much about a man who refuses to be hemmed in.

All are major success stories – and that’s before we even mention Virgin Rail, Virgin Books or fleeting efforts such as Virgin Vodka and Virgin Cola (there were even Virgin condoms).

Branson clearly knows what he is good at and when to delegate. This is why the chapters of Finding My Virginity in which he discusses overcoming difficulties and besting competitors are gripping. These include the court case that Branson insisted upon when Virgin Rail was denied Britain’s west coast route after what the High Court eventually agreed was an inferior bid from National Express.

Virgin rarely gets involved in the heavy lifting of research and development when getting a company up and running, but takes advantage of failing early entrants into the market. This low-cost strategy depends heavily on brand differentiation and customer focus – areas in which Virgin does seem to perform very well.

Branson also revels in Virgin’s irreverent approach to doing business and cheeky ribbing of the competition (when there were problems erecting the British Airways-sponsored London Eye Ferris wheel in 1999, for example, a blimp was sent up to hover over the site, its side emblazoned with the words, “BA CAN’T GET IT UP”). Similarly, Branson enjoys his informal, fun-loving image, relating how he literally cut off the tie of Delta Air Lines chief executive Richard Anderson.

Business takes up about one-third of the book, the billionaire’s toys take up perhaps another third, and Branson’s political activism and philanthropy the remainder. While raising his family is mentioned, Branson’s passion for space travel gets major play (he established Virgin Galactic with the goal of making space travel available to customers paying a US$200,000 deposit), but the gee-whizz talk on terminal velocities and space-age materials won’t excite every reader.

He writes of his experiences in assembling a team of statesmen dubbed The Elders, to advise world leaders. These have included Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Jimmy Carter, among others. It’s a ludicrous idea, of course, without political accountability or administrative logic (nobody likes a back-seat driver, after all), but he gets his chosen ones on board, showing perhaps the vanity of age.

Elsewhere, Branson claims to have sought to prevent the Iraq war, only to be foiled by then United States president George W. Bush’s early launch of hostilities. This section is eyebrow-raising, to say the least.

There is no doubt that the 67-year-old has lived a remarkable life, and his relish for living makes Finding

My Virginity an enjoyable romp: there’s no diffidence, fake humility or irony, whether he’s describing Necker, his astonishing home in the British Virgin Islands, mocking Donald Trump or shamelessly name-dropping.

Arranged in bite-size chapters, Finding My Virginity is matey and almost winsome, though its prose is functional at best. In this, it’s similar to Tony Blair’s A Journey (2010), which – though rich with political insight – lacked the elegance and irony of precursors by Roy Jenkins and Denis Healey.

Branson’s previous volume, Losing My Virginity, sold an impressive 350,000 copies, demonstrating his connection with the public (he is the most followed person on LinkedIn). He takes care to embellish his persona – amid the lunches with Barack Obama and friendship with Mandela – with tales of getting drunk and chatting up Jenson Button’s wife, and of working nine to five at Virgin Records: “9pm to 5am that is!” His insistence on being a “grand-dude” rather than a grandfather is emblematic of the ageing baby-boomer, reluctant to let go of his cool. He still wants to be thought of as a hippy.

Finding My Virginity is thus a mixed bag, with insight and innocence, shrewdness and vanity, glories and failures strewn liberally throughout. As such, it is unusually soul-bearing – in ways which Branson perhaps did not quite intend – once you read between the lines.