Review | Peter Carey tackles Australia’s racial history in new book

The two-time Booker Prize-winning novelist embraces the road-race genre as he ventures into territory he has managed to avoid thus far

A Long Way from Home

by Peter Carey

Hamish Hamilton

Back in the mists of time – well, the late 1960s to the early 80s – there was a golden age of the cinematic genre called, for want of a better phrase, the road race movie. Various teams of colourfully eccentric characters drive various colourfully eccentric cars around various colourfully exotic locations.

The attraction for both filmmakers and film-goers is not hard to see. Straightforward, but gripping plots (who will win?), fast or at least interesting cars and maximum potential for ensemble casts: hunky leading men, glamorous leading ladies and all manner of comic turns.

Most of these advantages are present in the masterpieces of the genre. From 1969 there’s Monte Carlo or Bust, which whizzed Hollywood royalty such as Tony Curtis, the cream of British comedy including Peter Cook and Dudley Moore, not forgetting Susan Hampshire, around Paris, Rome, Monaco as well as the titular principality.

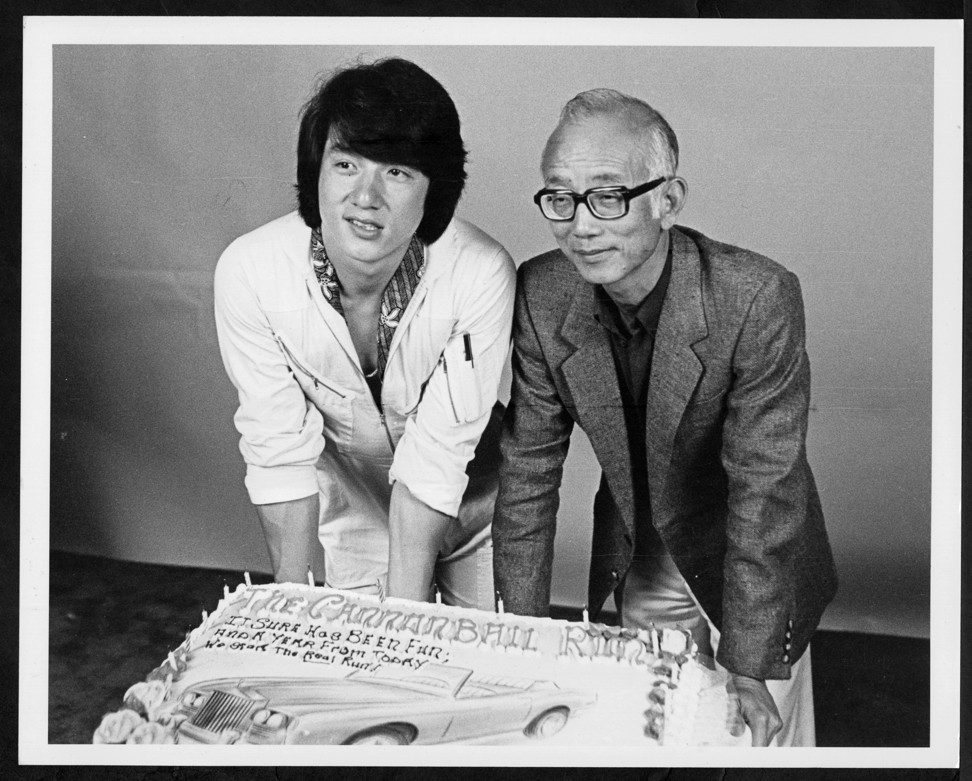

Arguably the most famous example is The Cannonball Run (1981), produced by Hong Kong’s Golden Harvest Films. Rougher and readier than Monte Carlo or Bust, it starred Jackie Chan, Burt Reynolds, Michael Hui Koon-man, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jnr, Roger Moore and Farrah Fawcett racing through Midwestern America.

The genre proved both successful and surprisingly diverse: the tone extends from the dark, satirical Death Race 2000 (1975) to the series of comic children’s movies starring Herbie the Volkswagen “love bug”. While the road race movie eventually crashed and burned, it didn’t take long for its ride to be pimped for the 21st century, most obviously with the massively popular Fast and Furious franchise.

I have no idea whether Peter Carey, two-time winner of the Man Booker Prize, with Oscar and Lucinda (1988) and True History of the Kelly Gang (2001), is a fan of Herbie Goes Bananas or Steve McQueen’s 1971 ego-vehicle Le Mans, but his latest novel, A Long Way from Home, extends the genre’s narrative possibilities.

There is, as most races demand, a beginning, a middle and an end, but none of these are quite what they seem, as Carey zooms backwards and forwards in time and place thanks to narrators who know how parts of their story turn out: “How could I predict […] what sort of life my heart’s desire would lead me to?” wonders our heroine, Irene Bobs, simultaneously looking back in time to look forward through her life.

“Our dad was still alive on the day I first set eyes on Titch. My babies were not yet born. I couldn’t drive a car […] There was not even a Redex Around Australia Reliability Trial although that, the greatest Australian car race of the century, is the story I will get to in the end.”

By a similar token, “road” hardly describes the perilous and heavily metaphorical terrain the cars had to overcome around the continent: “Then a talcum dustbowl. Then a switch of soil. We cut between grey banks. We banged over baked clay, into long ruts spiked with rocks and roots. It was said the real Australia is beautiful, but not by me.”

As this suggests, Carey is encapsulating a nation and its history, which means by extension its people. His cast of outlaws, outsiders, drifters and ambitious failures undercuts the Redex’s public claim on moderation as successfully as the course: “As for the police themselves, they hated us. They knew what the rule book would not admit, that the drivers were all maniacs, gathered to race, to burn each other off, to ‘do the ton’, to get ahead, to make up time, to sometimes create breathing space for adjustments and repairs but always, no matter what they said in interviews, to make the other fellow ‘eat my dust’.”

Carey’s cast is essentially a trio. Our first of two narrators is the stylish, if stylised storyteller Irene Bobs, who hitches her wagon to Titch Bobs, a diminutive, strong and charismatic car salesman, who has claims on being the best in southeastern Australia. Irene and her two children are not the only forces shaping Titch’s destiny. The others are his quenchless desire to open a Ford car dealership and his father, Dangerous Dan, whose bullying, abusive parenting style drives Irene to despair, but is endlessly forgiven by Titch himself.

For Irene, Titch’s superficial cheery matiness and his near-desperation to make others laugh, compensate for formative cruelty: “He wore long-sleeved shirts, always buttoned, to hide his scars. Cigarette burns. These were for me to see, to cry on for our wedding night. So this is why he shines, I realised then. So this is why he jokes. I held his perfect head against my breast, and had no clue about the damage.”

Irene effectively funds Titch’s tilt at the Redex: he was meant to spend the money on securing a dealership with Ford’s rivals, General Motors, but gambles the lot on the promise of fame and improved prospects that victory will bring.

Enter the third side of the triangle, Willie Bachhuber, who will navigate the Bobses’ car around Australia. Unlike Dangerous Dan Bobs (born Daniel Bobst), Willie does not attempt to hide the Germanic origins of his name. Yet this honesty is deceptive as he has more skeletons in his closet than even Titch. We quickly learn he has left his wife and young son after, so he claims, being cuckolded by a former friend. Fleeing to Bacchus Marsh, where he will meet the Bobses, he tames the worst class in the local school only to crash once more when he dangles one of his troublesome charges out of a window. The cause of the scandal – an argument over the pejorative term for refugees – haunts the novel.

Carey pulls few punches when Willie and Irene discover the skeletons of a murdered Aboriginal family: a child’s small skull has a bullet hole. The passage’s political symbolism is crudely effective: Irene stumbles upon the graves while emptying her bowels

Willie fills his days by competing as the reigning champion on a fake local radio quiz show, with ambitions to go national in the near-future. His erotic passions are secretive, too: first for his long-running rival in radio trivia, Clover, and then for Irene herself.

Willie’s impact on the story lends powerful emphasis to the idea of “race”. Set less than a decade after the second world war, his German roots (his father is a pastor who fled Adolf Hitler) carry discomforting accents for many Australians who defended the empire in the conflict. Yet it is Australia’s disquieting relationship with its own racial history that absorbs Carey.

The Redex brings Willie and Irene into face-to-face contact with the country’s Aboriginal people for the first time. Willie’s sensitivity when reading about the violence done to the native population intensifies with his actual encounters. Carey pulls few punches when Willie and Irene discover the skeletons of a murdered Aboriginal family: a child’s small skull has a bullet hole. The passage’s political symbolism is crudely effective: Irene stumbles upon the graves while emptying her bowels.

The shocking insights into Australia’s origins (Irene wonders how this savagery is possible in the “modern” world) run parallel with revelations about Willie’s own background, and set off earthquakes beneath Carey’s title.

Whose home is Australia anyway? In a country where almost everyone has adopted it to some extent, who exactly is Australian? By presenting these questions of national identity in the form of a race – where money, fame, acceptance and lives are literally on the line – Carey demands that we consider who the winners and losers are.

Of course, one challenge of a circumnavigational contest is you end up pretty much where you started. Viewed in terms of cultural and social progression, this paints a bleak picture: the more things change, the more they stay the same, especially for dispossessed and abused indigenous people. But then this is a road race movie scripted by Peter Carey. It is enjoyable, vibrant but deeply sobering.