Review | Talk Art: Russell Tovey and Robert Diament attempt to make contemporary art more accessible

- A spin-off from the popular podcast of the same name, Talk Art is unashamed to address any question, however naive

- The authors insist that collecting contemporary art need not be an expensive hobby, with a vast variety of art available on a budget of £500 (US$700)

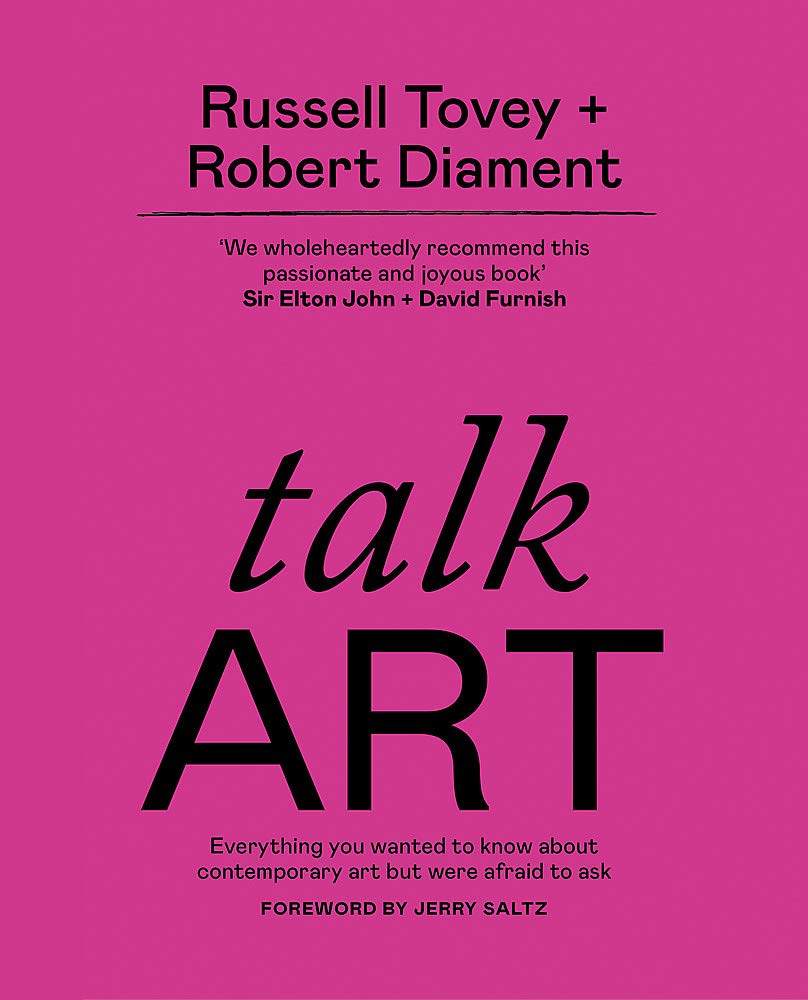

Talk Art – Everything You Wanted to Know About Contemporary Art but Were Afraid to Ask by Russell Tovey and Robert Diament. Ilex Press

Contemporary art, in the view of Russell Tovey and Robert Diament, authors of Talk Art, is seen as a forbidden topic of conversation. The well-illustrated book, a spin-off from the wildly popular podcast of the same name, is subtitled “Everything You Wanted to Know About Contemporary Art but Were Afraid to Ask”.

“Over the years,” they write, “we’ve all been taught to follow the rule: don’t ever consider discussing religion and politics when under the influence of alcohol.”

They have omitted the long-established social fatwa against talking about sex, but then that’s frequently the topic of the art they discuss, and it’s discussing art that is the new taboo.

The issue is not the risk of giving offence, but rather the fear of embarrassment – the dread of being in a gallery with a friend and actually having to say something, and perhaps reveal you have no idea what you’re supposed to think or say.

This nervous reticence may be a peculiarly British characteristic, mentioned in what is overall a peculiarly British book, dealing mostly with British artists and collectors, and London gallery-going, yet universal in its ideas. But even Victorian high priest of art criticism John Ruskin wrote condescendingly that the average person is incapable of knowing what he or she ought to like.

Tovey and Diament want to reassure you that it’s perfectly fine not to like much contemporary art, but they want to share their own feelings about the rewards of looking for something with which you can fall in love, preferably without first reading any wall-mounted explanation of what you are supposed to see in it.

Their approach is heartbreakingly earnest, occasionally silly, but unashamed to address any question, however naive: “‘Why does putting an object into a gallery suddenly make it art?’ ‘Why do artists take paraphernalia and experiences of the everyday, give it their ‘artsy’ spin, then claim it to be of importance?’”

Their tone is partly drug rehabilitation programme (“We are Russell and Robert, and we are art addicts”) and partly an encouragement to others to come out of the closet – to discover and to reveal their inner aesthetes.

Podcast and book alike are in the manner of actor Tovey’s regular-bloke-but-with-a-brain persona, seen in various versions on stage (The History Boys), on film (The History Boys again), and television (Doctor Who, Sherlock, Quantico, etc). He has tapped into a network of media mates and artists he loves for comment, and as a gay icon he’s been able to attract contributions from yet brighter stars in the constellation of camp – collectors and commentators such as Stephen Fry and Elton John.

But mostly this is him and mucker Diament, a retired electropop-band frontman (for Temposhark) turned gallerist, sharing a warm friendship that began with a particular enthusiasm for the drawings of Tracey Emin, whose My Bed (1998), complete with stained underwear and a used condom, may have sold at auction for about US$4.5 million in 2014, but who still produces limited-edition prints at affordable prices.

Collecting contemporary art, they insist, need not be an expensive hobby. Wandering around galleries on foot or online with a budget of £500 (US$700) still makes a vast variety of art available, such as prints from emerging or even established artists.

Despite their attempts to make the often alienating art world accessible, with much plain-spoken, sensible and practical advice for viewer and shopper alike, they occasionally slip into artspeak but nevertheless remain breezily unselfconscious and not ever afraid to ask simple questions of their interviewees, to use terms such as “humungous”, or to mispronounce (in the podcast) the name of “Proust”.

Various artists beloved of the authors are given potted profiles. Hong Kong’s Wong Ping gets a mention. KAWS’ Holiday (Hong Kong), a 37-metre-long inflated figure that floated in Victoria Harbour in 2019, appears between a discussion of street art and the ponderous metal acne of Henry Moore’s sculptures. Protest art, cartoon art, performance art, seen-every-day street art and official public art are all introduced.

Antony Gormley’s vast sculptures such as Angel of the North, in Gateshead, Britain, have transformed many a backwater into a place of pilgrimage. In a recent British poll, street artist Banksy’s Girl with Balloon (2002) beat John Constable’s The Hay Wain (1821) and J.M.W. Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1839) as the most popular British picture. Some art critics decry Banksy as crass and obvious while still going into ecstasies over the equally shallow simplicities of Ai Weiwei. But perhaps Banksy is a gateway drug – a way into art addiction.

Tovey and Diament suggest highs await.