Gay Games Hong Kong co-chair on the ancient Chinese text that helped her embrace being a lesbian

- Lisa Lam, co-chair of the Gay Games Hong Kong, read the Zhuangzi at school at a time when she began to realise she had intense feelings for women

- Among the many things the text gave her was some space in her heart ‘to look in peacefully and ignore what was going on outside’

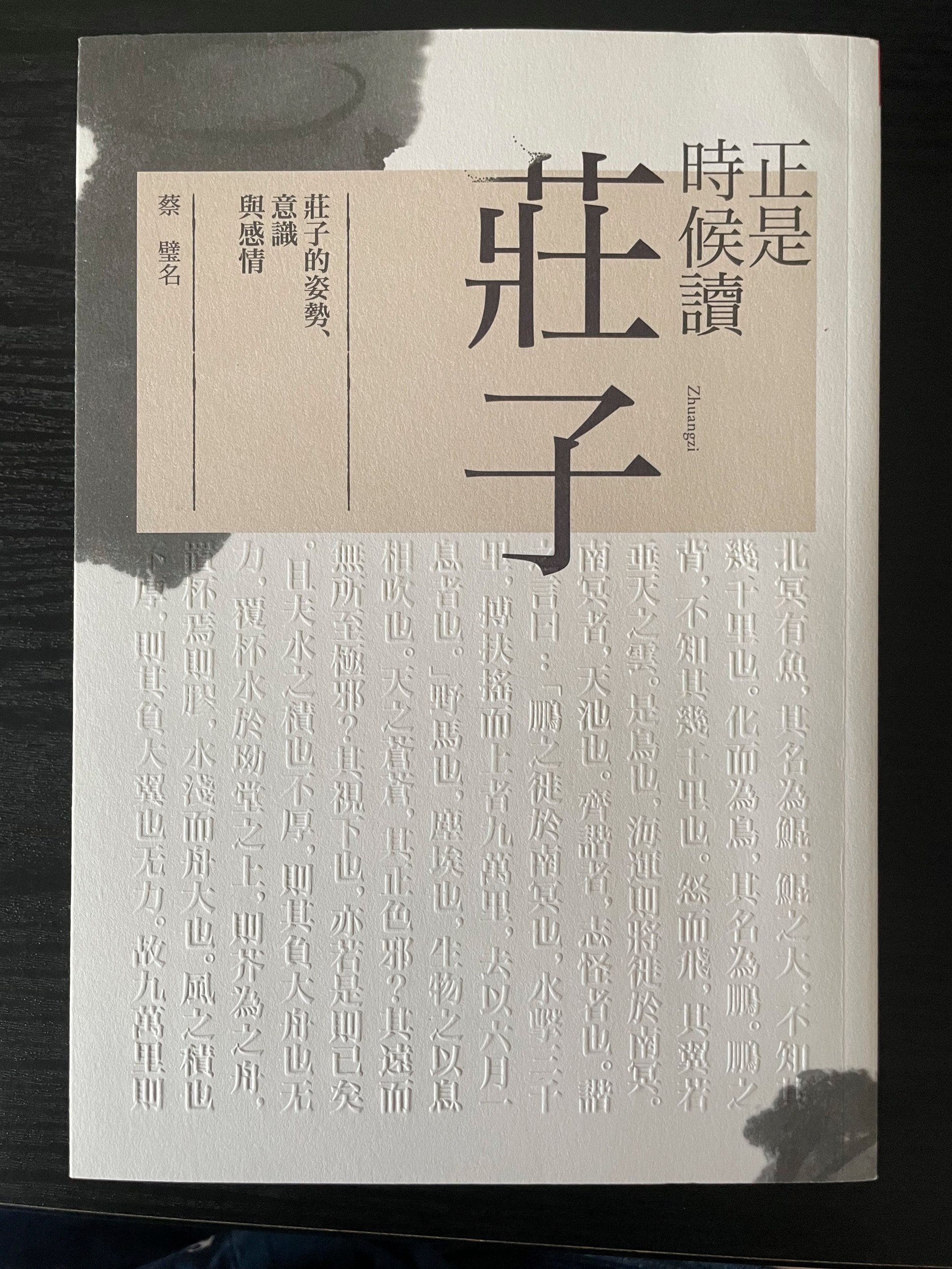

A foundational work of Chinese philosophy and literature, the Zhuangzi, traditionally attributed to the philosopher of the same name from the late Warring States Period (475-221BC), is a series of stories, anecdotes and parables that advocate independent thinking and freedom from societal conventions.

Lisa Lam Mun-wai, co-chair of the Gay Games Hong Kong – which will start on November 3, the first time the event has visited Asia – tells Richard Lord how it changed her life.

The first time I read it was as part of the school curriculum, in grade eight or nine. It guided me mentally and emotionally through challenges. This was around the time of my coming of age as a teenager, when I realised I was a little bit different from my friends.

I had these intense feelings for women – I had no words for it, and I felt quite lost. This was in the early 80s, and all you saw around you was that lesbians would have a miserable life or were lunatics or serial killers.

Among the many things Zhuangzi gave me was some space in my heart to look in peacefully and ignore what was going on outside.

He says that it’s not wise to give labels to things, and nothing is entirely either good or bad. We humans are limited by our perspective: something can be useful to me and completely useless to you.

Zhuangzi was very comforting to me at that time because the outside world was so nasty and unaccepting. I realised that it didn’t mean I was a lonely person who had to live a miserable life. It really gave me a chance to look inside, and space to breathe.

‘I was in tears’: how Questions for Ada changed this NGO director’s life

The first story I read from it was the butcher (Cook Ding, whose movements are so skilful that, as he explains while butchering an ox, he has not had to sharpen his knife for 19 years). As I grew older, I started to understand the symbolism of that. It’s in a chapter about how to nurture life.

If you look at the cow as your life journey, the knife is like your heart and the butcher is how you navigate through life: the whole story is about how you stay centred. For me, it was about how you preserve your heart.

Zhuangzi lived during a terrible time in Chinese history, and he was trying to show how despite suffering, you can still live a good life.

At the beginning of the chapter, before the butcher story, there’s an opening paragraph about how your life is limited but knowledge is unlimited.

I was 13 or 14 and had never thought of life being limited. I did a calculation: I thought I had about 20,000 days left on Earth. Do I want to spend them worrying how people think? It became crystal clear to me that I wanted to lead a meaningful life.

I go back to it from time to time, especially when I feel stuck or unhappy. Zhuangzi taught me how to be open-minded and not cling onto fixed views or ideas.

If he were alive now, he’d probably be an environmentalist. He constantly talks about how humanity is just one of many beings. We feel superior and try to fix things, not realising that there are lots of things we don’t know.