The key to Chinese cooking ‘lies in understanding the basic techniques’, writes Irene Kuo

- In her cookbook, Irene Kuo – a China-born, US-raised influential restaurateur – delves deep into a vast cuisine

- ‘The Chinese have had the dire need to experiment on all things edible for survival and the leisure of prosperity to perfect their cooking,’ she writes

Chinese cuisine is famous for using every part of an animal and for turning humble ingredients – including some considered inedible by other cultures – into something luxurious. Dishes containing white truffles, saffron and beluga caviar are expensive because the supplies are limited or difficult to harvest, but it is less obvious why swiftlet spit (bird’s nests), dried scallops and dried abalone are so expensive (hint: it is for similar reasons).

In Chinese cuisine, a dish containing less expensive ingredients can be costly if the cooking process involves a lot of work: the snake soup at an exclusive private kitchen in Hong Kong is complex because it contains five species of snake and all the ingredients – including fish maw and aged tangerine peel – are finely sliced by hand. At the same restaurant, even pork stomach (tripe) is elevated to another level (and also expensive) because the ingredients are so precisely prepared.

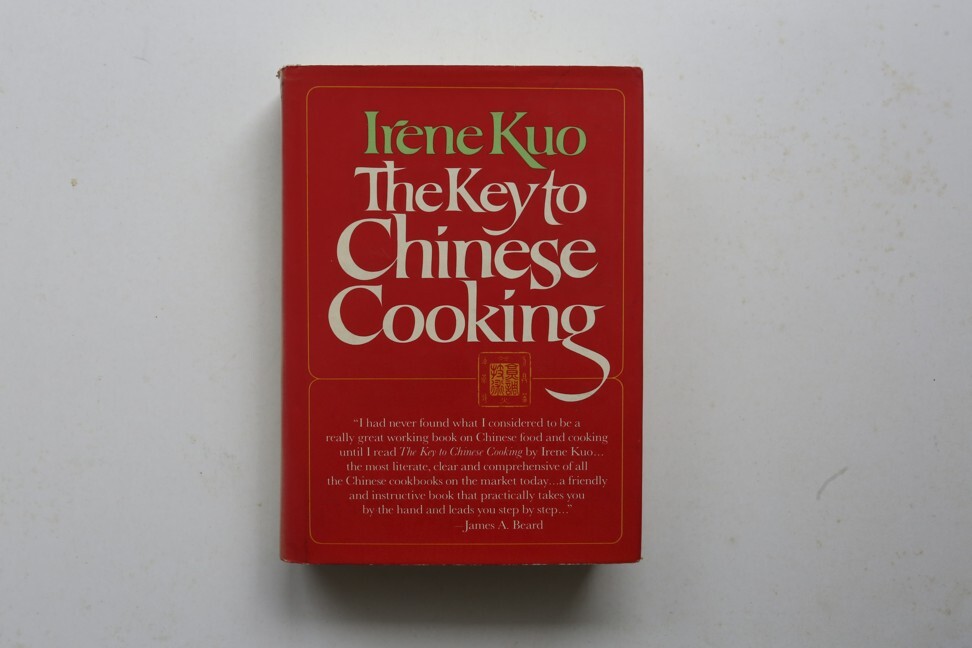

In the introduction to her book, The Key to Chinese Cooking (1977), Irene Kuo – who was born into a wealthy family in China, went to university in the United States, opened restaurants in New York and died in California in 1993 – explains how this came about.

“Over the centuries, having been alternately buffeted by famine or warfare and blessed with the splendours of great civilisation at peace, the Chinese have had both the dire need to experiment on all things edible for sheer survival and the leisure of prosperity to perfect their cooking techniques for sensual enjoyment. They eat boiled bark, weeds and roots when there is nothing else; they eat shallow-fried transparent prawns from preference, jasmine blossoms out of poetic sentiment, and wine-braised camel’s hump from blatant extravagance.

“Out of this realistic earthiness, the Chinese developed a healthy respect for food and concluded a long time ago that good eating is always a matter of good cooking, which means knowing the inherent qualities of the food itself and how different techniques can subtly alter flavour and texture […]

“Basically, Chinese food is brought from the raw to the cooked stage through four mediums: water, oil, wet heat (steam) and dry heat (roasting). From these, the Chinese have developed an elaborate string of cooking techniques, ranging from the familiar procedures of boiling, simmering, stewing, braising, steeping, steaming, deep-frying, roasting, baking, grilling, barbecuing, curing, preserving, smoking, and the cold-stirring of salads to more specifically Chinese methods, such as stir-frying, red-cooking, pan-sticking, slithering, exploding, plunging, purifying, smothering, mating, nestling, capturing, choking, flavour-potting, light-footing, sizzling, rinsing, scorching, drowning, wine-pasting, and intoxicating.”

Don’t worry if you haven’t heard of some of these cooking terms: Kuo explains that many of them are known only to professional chefs.

“Many people, while loving Chinese food, are hesitant about cooking it at home because of the prevailing impression that the cuisine is totally committed to tedious cutting and split-second timing. In reality, these are found in but one corner of Chinese cooking – the stir-frying technique.

“On the whole, preparing a Chinese meal is leisurely and free from tension. There are slow methods of cooking and many recipes use whole or chunky ingredients. Even seemingly complex ingredients are fundamentally carefree, since they are based on simple preparational procedures, which can be done long in advance,” she writes.

“The key lies in understanding the basic techniques – how and why they are used, what they will do to food.”

Kuo’s recipes include sweet and sour pork, stuffed bean curd, red-cooked beef, boneless whole chicken with rice stuffing, deep-fried meatballs with kumquats, shrimp toast, beer-roasted duck, stuffed cucumbers in parsley sauce, dry-seared green beans, and noodles with bean-paste meat sauce.