‘We could 3D-print Trump’s wall’: China construction visionaries set to revolutionise an industry rife with graft and old thinking

Three days to build a villa, and a tower that rises by three storeys a day - between them Ma Yihe, 3D-printing proprietor, and modular architecture pioneer Zhang Yue may hold the keys to building industry’s future

“Donald Trump could build his wall much cheaper and in less than a year,” Ma Yihe says, laughing, although he is not joking. “We could definitely do it. Maybe at around 60 per cent of the projected cost and three to four times faster.”

Ma is the founder and chairman of WinSun, a Jiangsu province-based company that doesn’t hide its ambitions. “We print architecture’s future,” claims its brochure. And that’s no idle boast: in 2008, WinSun became the first company in the world to use a 3D printer to create a building, and its projects have grown considerably in stature since then.

“Last year we developed 80- and 130-square-metre Chinese-style courtyard homes. It took just two days to print and put them together,” says Ma, in a suitably futuristic conference room. “And we were also the first to create a five-storey residential block – built in just a month – in a factory [in 2015].”

Even WinSun’s huge plant, in Suzhou Industrial Park, was 3D-printed. Inside the grey rectangular cube, photographs of the company’s best-kept secret – a 150-metre-long, 10-metre-wide and 6.6-metre-high 3D printer – are forbidden. Except for the 100 or so workers operating the machine, who have had to go through strict security clearance, few staff have seen it.

“It’s our core technology,” says Ma. “It can work either with traditional architectural plans or with highly detailed 3D models. We already have 129 international patents – including those for the spray nozzle and the composite materials – and, obviously, we worry that it will be copied.”

Indeed, Ma is convinced that he is about to trigger a revolution in construction, an industry he claims has changed little in the past century, even though it represents about 5 per cent of China’s gross domestic product.

According to business intelligence publisher IBISWorld, the 26,000 companies in this sector in China employ 31 million people, have a revenue of US$2 trillion and grow at an average of 9 per cent a year. Yet “despite the power of the industry, there has been almost no innovation in building techniques, resources are wasted constantly and it’s a very opaque sector, a magnet for corruption”, says Ma.

“[With 3D-printing technology] we can solve most of these problems,” he promises.

According to Ma, 3D printing reduces the need for new construction materials by between 30 per cent and 60 per cent, saves 50 per cent to 70 per cent in construction time, uses 50 per cent to 80 cent less labour and is up to 50 per cent cheaper.

“We make our own ‘ink’ using 100 per cent recycled materials. That includes waste from industries and demolition of large buildings, and mine tailings,” he says. “We can create new composite materials that are not only eco-friendly but also have improved properties. The high plasticity of our special glass-fibre reinforced concrete, for example, gives good anti-seismic and wind-load resistance.”

Wonderful they may be, but WinSun’s first generation of 3D-printed buildings, which I visited on the outskirts of Shanghai in 2014, are painfully ugly. The 60-square-metre one-storey houses, which at the time Ma thought could help alleviate poverty in developing countries because they cost just HK$30,000 each to print, have rough concrete walls, each layer of which is clearly visible, like a stack of crêpes.

“No architecture or design company wanted to work for us, so I drew the first prototypes myself and, yes, they were ugly,” Ma concedes, with a broad smile. “We persevered and our technology has evolved.”

To make the facades more appealing, WinSun has developed what it calls “crazy magic stone”.

“It looks like natural stone but it’s actually a beautiful composite, with properties that make it more durable,” says Ma, as he displays a variety of colours and textures.

The newest WinSun prototypes, which include a Western-style villa, look and feel like regular buildings, although the fact the “bricks” come on screwed-together panels will be noticed on close inspection. Inside, the homes are cosy. Here and there, the designers have cleverly revealed the work of the 3D printer, which blends with the rest of the decor to exude an artsy feel.

“We can make it look however you want,” says sales assistant Cao Gence, during a tour of WinSun’s facilities.

As part of trials, some employees have moved temporarily into “the world’s tallest 3D-printed building”, a five-storey block next to the factory, and, we’re told, report no disadvantages when compared with their own homes.

“The fact that the buildings are printed at the factory also drastically reduces pollution on-site. There will be much less dust and noise in cities,” Ma says. “And because we have developed a special inner structure for walls – where the 3D printer draws a zigzag support pattern between outer and inner panels – insulation is easily installed and much more efficient. Our buildings will use 40 per cent less energy than regular ones.”

I want our buildings to become a tool to fight pollution, climate change and corruption, which are the greatest threats humanity faces

According to Wang Qingqin, of the China Academy of Building Research, new buildings in China consume an average of two to three times more energy while maintaining a comfortable temperature than those in the United States and the European Union. The heat transfer coefficient – which measures the efficiency of insulation – in China’s buildings is especially bad when it comes to windows and roofs.

In 2011, Tang Kai, chief planner of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, admitted that 95 per cent of all new buildings in China were “energy guzzling”.

“We have to be aware that the promotion of energy-efficient buildings is imperative and extremely urgent for the national economy to achieve sustainable development,” he said, according to Xinhua.

Not much has changed since 2011, says Ma.

Additionally, he points out, production costs where 3D-printed homes are concerned are transparent and “there are no surprises in the budget”, which, he adds, is bad news for corrupt officials. The Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Centre seems to agree with him, because it cites “uniqueness that makes comparisons between projects difficult”, “complex transaction chains” and “materials and workmanship often being hidden” as the main reasons why the construction industry is among the most corrupt in China.

“In WinSun we have a catalogue of prototypes, almost no intermediaries, and all costs are clearly stated,” says Ma. He prefers to say that “China is more reluctant to embrace innovation”, but perhaps the transparency involved in 3D printing is why WinSun is having more success abroad than at home. In Dubai, for example, the government has recently purchased 17 of his office buildings, all printed in Suzhou and exported in containers, and he expects orders to keep coming.

“They told me their goal is to make a quarter of all new government offices using 3D-printing technology,” says Ma.

WinSun plans to licence the technology so that everything can eventually be printed locally.

In contrast, although he is now developing two big compounds for a developer in Shanghai and a few WinSun office buildings are in use across the nation, his business in China mostly consists of small public infrastructure projects, such as bus stops and public toilets. But Ma shrugs and offers a carefree smile.

“Last year, for the first time since we established the company, in 2002, we were profitable,” he says, and he is now busy with his biggest project to date.

“We will be supplying the pillars and interior seats” for Hyperloop, a high-speed transport initiative, proposed by billionaire US tech entrepreneur Elon Musk, that is based on the propulsion of vehicles through tubes. “Everything will be 3D printed here using recycled materials.”

Sensing a demand for furniture and fixtures, WinSun began designing and printing everything from glass-fibre-reinforced gypsum ceiling lamps to fibre-reinforced plastic chairs and tables.

“I believe our business will grow exponentially thanks to the licensing of technology and the sale of ‘inks’,” Ma says. “We want to make money, of course, but we want to do it conscientiously. China used more concrete between 2011 and 2013 than the US did in the entire 20th century. If we keep our way of life, Earth’s resources won’t satisfy our needs.”

A thousand kilometres to the west of Suzhou, in central Hunan province’s capital, Changsha, another man shares the environmental worries of Ma and also feels the construction industry should embrace dramatic change. But Zhang Yue, president of Broad Sustainable Building (BSB), proposes a very different solution. He is betting on modular architecture.

“It is a cheap, green, safe and clean formula,” he says. He uses the last adjective in reference to both the dust produced during construction and the thick hongbao envelopes that typically change hands during project negotiations.

“I want our buildings to become a tool to fight pollution, climate change and corruption, which are the greatest threats humanity faces,” he says. “I want our model to signal a new era for architecture.”

If you are thinking modular architecture is suitable only for small homes, think again. In 2015, BSB built Changsha’s 57-storey Mini Sky City – and did so in 19 days.

“The parts of the standard buildings we have in our catalogue are mass produced in our facilities, with all pipes, wiring and air ducts ready for connection,” says Jiang Yan, BSB’s vice-president in charge of international markets. “They are transported to the building site and assembled there by our qualified staff. It’s like building a Lego kit. There is hardly any outsourcing, which helps maintain a low cost and strict quality control, and allows us to eliminate the corruption inherent in the sector.”

The size of the BSB headquarters is astonishing. Thousands of workers fill what many call Broad Town, which includes huge factories, a replica of an Egyptian pyramid and a Versailles-style palace. In the production plant, giant building pieces are made and tagged carefully; there is little margin for error when they are being assembled on-site.

“The worthiness of this system has been verified by the more than 50 buildings erected throughout China without a single fatality in the process, and Mexico’s former president Felipe Calderón inaugurated the first BSB building in Latin America,” says Jiang, referring to Cancun’s COP16 Broad Pavilion, while leading an inspection tour of rooms in the Ark Hotel, a 15-storey block that BSB built in six days and now uses as a showcase at its headquarters. “Because of the global economic crisis, awareness of lower production costs is growing, so it’s a good time to develop new techniques.

“In China, for example, our construction methods are between 10 per cent and 30 per cent cheaper, while in countries like Saudi Arabia or Brazil, where labour costs are higher, savings climb to between 30 per cent and 50 per cent. And we have shown that maintenance is also much cheaper. The T30, our flagship product, would consume 2.3 megawatts in air conditioning if it was built conventionally, but it only needs 10 per cent of that amount of electricity,” Jiang says, explaining that good insulation is complemented by a non-electric air-conditioning system developed by BSB’s parent company, Broad Group.

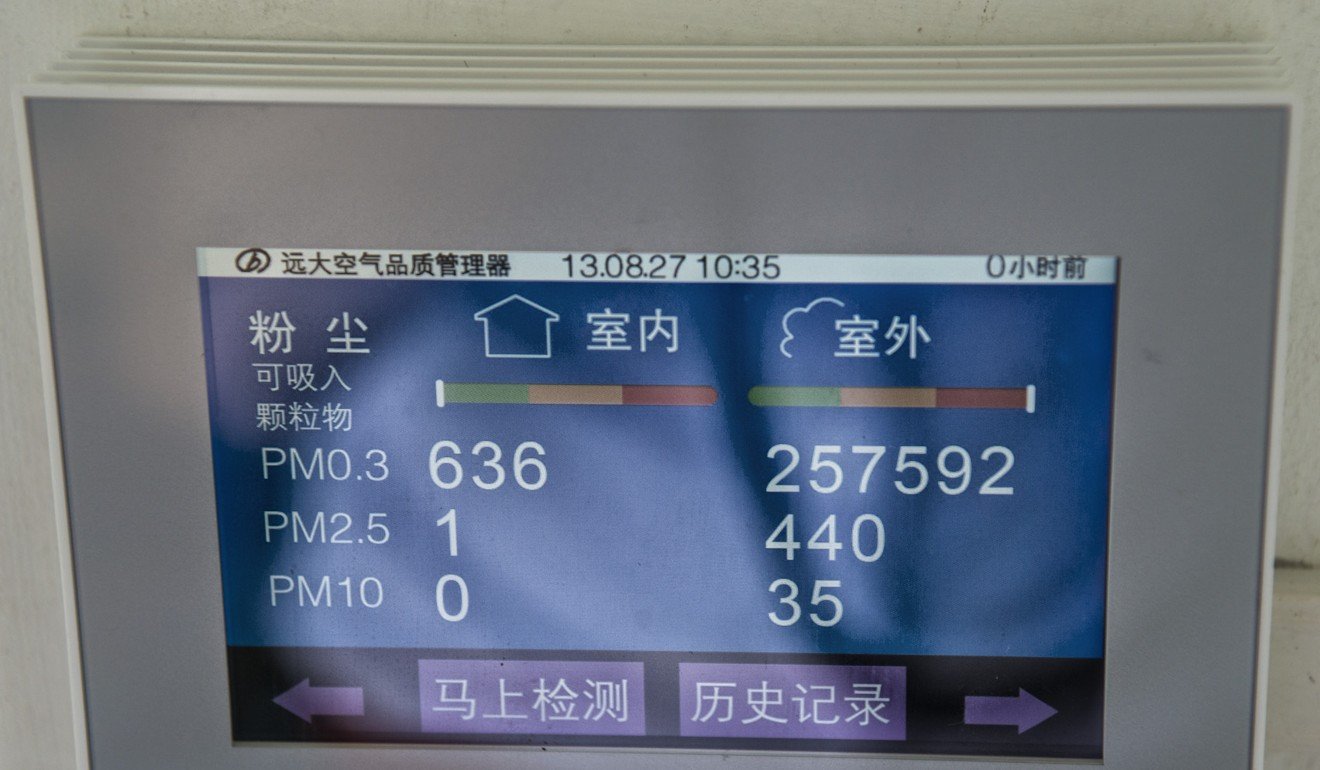

Furthermore, the air inside BSB’s buildings is clean. Purifiers manufactured by the company take care of that, and their effectiveness is shown in LED screens throughout the towers. While the grey air of Changsha has a PM 2.5 level of 400 micrograms per cubic metre – a measure of fine dust particles in the air – when I visit, the level is just 10 micrograms per cubic metre inside the Ark Hotel.

And as if that were not enough, each living unit has a system of waste separation and recycling.

“You just need to throw each thing in its tube – which are clearly marked and coloured. The waste goes directly to a collection point in the basement, from where it is sent for recycling,” Jiang says. (This particular feature would be beneficial only in countries that have well-developed rubbish-recycling programmes, of course.)

Except for the sealed windows, the noise the thin plasterboard walls are unable to keep out and the lack of aesthetic appeal, BSB’s model seems to be a winner. Zhang, however, has not yet managed to make his biggest dream come true.

“They would have everything they need, from the delivery room to the funeral home,” Zhang says, with a grin.

The authorities, however, were not convinced. They ordered a halt to all work in 2013, a day after BSB began building the foundations of what was expected to be a nine billion yuan (HK$10.14 billion) landmark that would take 13 months to complete. The inauguration shovel now rests beside a miniature model of the skyscraper, with a red ribbon still attached to the shaft. Last year, the Changsha government declared the Daze Lake wetlands, the intended location for Sky City, a protected environment with a strict no-construction policy.

Zhang won’t say why a project that had already been given a green light and had made headlines all over the world was suddenly halted, and the authorities in Changsha didn’t reply to Post Magazine’s queries, but the BSB president denies it was for the safety reasons some officials have suggested. To prove it, he shows us a video of tests in which scale models withstood a magnitude 9 earthquake.

“Sky City is a threat to the construction industry,” an employee who wishes to remain anonymous tells us later. “If this system becomes widespread, many could end up bankrupt.” Others would find it more difficult to secure backhanders, he adds.

Still, Zhang hasn’t given up on Sky City. He doesn’t know when or where, because buildings higher than 350 metres require authorisation by an increasingly reluctant central government, but he will realise his dream, he says.

China’s construction is of low quality and wastes lots of resources. Something has to be done

At 204 metres tall, Mini Sky City took less than 20 days to build at an average rate of three floors a day.

“That confirms [Sky City] is feasible,” he says.

Feasible, perhaps, but BSB has had to deal with those who complain that its 800 apartments are not as cheap as promised. Units in Mini Sky City cost about 12,000 yuan per square metre, above the market price for Changsha but well below what you would pay in the bigger cities or Hong Kong (units at Harbour Glory, in North Point, sold for up to 380,000 yuan per square metre last month).

“The price includes all the installation and even the interior decoration,” Jiang counters.

“It will take time for the world to accept my achievements,” Zhang says. “But it’s fine, I have time.”

The construction techniques being touted by Ma and Zhang offer clear advantages but “they will face strong resistance in the industry, which is reluctant to change”, says Julen Asua, a Spanish architect with CNA Smith Group who has been working in Shanghai for almost seven years. “But we can’t forget that innovation has been mocked many times in history.

“A good example is New York’s Empire State Building, which was built in just 13 months [in 1930-31]. Many thought it would be a failure, and for some time it was known as the ‘Empty State Building’. But time has shown that those who despised the project were wrong.

“China’s construction is of low quality and wastes lots of resources. Something has to be done.”

And like many other experts, Asua sees these ideas as just stepping stones.

“Architecture is mostly absent,” he says. “This is an engineering product and the buildings look like clones from some dystopian city created by visionary architects in the 1960s. The human side is neglected.”

Jiang admits, “We do sacrifice beauty for practicality.”

What many without a vested interest agree upon, however, is that the world urgently needs a change in the way buildings are put together. And adding gardens to rooftops, a trick Chinese developers are increasingly using to tout their projects as “green”, is not enough.

“That’s like using a band-aid to stop bleeding from an amputated limb,” says Jiang.

So-called zero carbon buildings represent a positive step but fall short of the revolution the industry needs, because they are difficult to replicate en masse and still tend to be traditional at their core.

If Ma and Zhang are right, the housing and offices of the future won’t grow from a building site, they will be produced in a factory.