Scapegoats or traitors? The tale of the British radio propagandists in wartime Shanghai who were convicted in Hong Kong

Seventy years ago, two broadcasters for a German radio station were found guilty of assisting the enemy. Collaboration was rife, so why were these Britons singled out while so many others went unpunished?

A court case that made headlines in Hong Kong 70 years ago this summer exposed the murky world of collaboration in wartime Shanghai, where a cast of shady characters helped the Axis propaganda effort, some becoming unlikely radio stars.

On the overcast morning of Sunday, June 29, 1947, one of the leading Nazis in Asia was discreetly taken to Kowloon Wharf No 1 and escorted aboard the passenger liner Empress of Scotland, which was anchored in Hong Kong’s war-ravaged harbour. Baron Jesco von Puttkamer was being repatriated to Europe, to begin a long term of incarceration.

Having been director of the German Information Bureau in Shanghai – the largest Nazi propaganda office outside Berlin – during the second world war, von Puttkamer had been interned temporarily at Victoria Prison, in Central, while acting as a key prosecution witness in two highly sensitive trials that had taken place the previous month, referred to in official memos held at the Public Records Office as the “Johnston/Gracie case”.

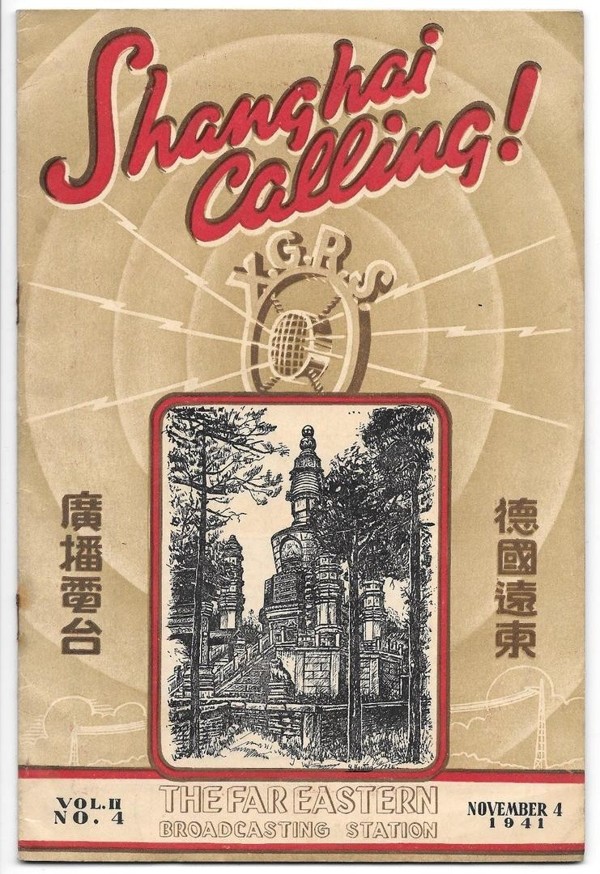

Von Puttkamer’s powerful weapon in the long-running propaganda war with the Allies had been the radio station XGRS (“X” was used to denote China and “GRS” stood for German Radio Station), and two British subjects, Frank Henry Johnston, 41, and John Kenneth Gracie, 49, stood accused in Hong Kong – in the nearest British-run court to Shanghai – of being his star broadcasters.

“There were newspapers, too, but radio was very important, especially during the Japanese occupation of East and Southeast Asia, as XGRS broadcasts could be heard in Hong Kong, Singapore and as far away as Australia and the west coast of the USA,” says Horst H. Geerken, author of Hitler’s Asian Adventure (2015), which devotes a chapter to the exploits of XGRS.

Gracie and Johnston were convicted of assisting the enemy. In Hong Kong, a city that had suffered under Japanese occupation, these were open-and-shut cases.

Gracie’s trial lasted one day and the jury did not retire to consider their verdict. The Scot told the court that, because his wife and child were Japanese, the British Residents’ Association in Shanghai had left them to “sink or swim”, so he had been forced to take up any job to “get bread for them”. His lawyer emphasised his distinguished first-world-war army record, but he was sentenced to 10 years hard labour, to be served in Hong Kong, for what Mr Justice Williams called an “offence of enormous magnitude”.

Johnston, who represented himself, managed to drag his trial out a little longer and claimed he had tried many times to enrol for the Allied military service, including once in Hong Kong, before turning to broadcasting in desperation. But he too received a 10-year sentence.

The colonial authorities knew the Johnston/Gracie case was the tip of the iceberg when it came to Allied collaboration, treachery and espionage in wartime Shanghai, but the worst offenders would never be fully investigated or brought to justice.

“With its lurid vice, savage criminality and conspiratorial politics, no place on earth in the late 1930s and 1940s better exemplified the twilight zone of clandestine warfare than Shanghai,” writes Professor Bernard Wasserstein, in his book Secret War in Shanghai (1999).

The historian explains that the foreign concession had become an isolated cosmopolitan island in a “sea of Japan” since the Battle of Shanghai (August-November 1937) but it continued to be the media centre of East Asia after the outbreak of the second world war in Europe, in September 1939.

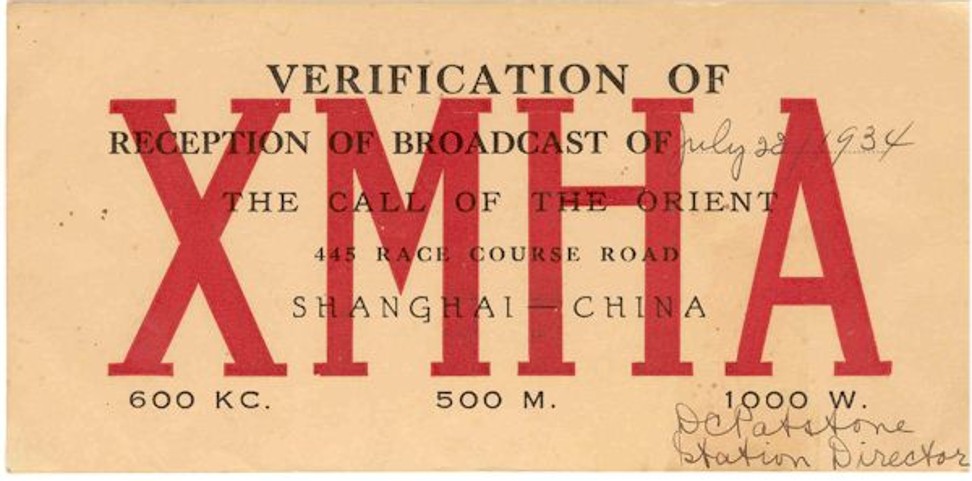

There were countless newspapers and periodicals published in several languages in the city, including four English-language titles, and XGRS was one of 40 radio stations. Most broadcast Chinese-language programmes sympathetic to the Nationalist struggle (much to the annoyance of the Japanese) but each foreign community had its own station operating in its mother tongue, including XQHA (Japanese), FFZ (French), XIRS (Italian) and XRVN (Russian). The British-owned XMHA and XCDN were the broadcasting arm of the respected North China Daily News newspaper, known fondly as the “Old Lady of the Bund”.

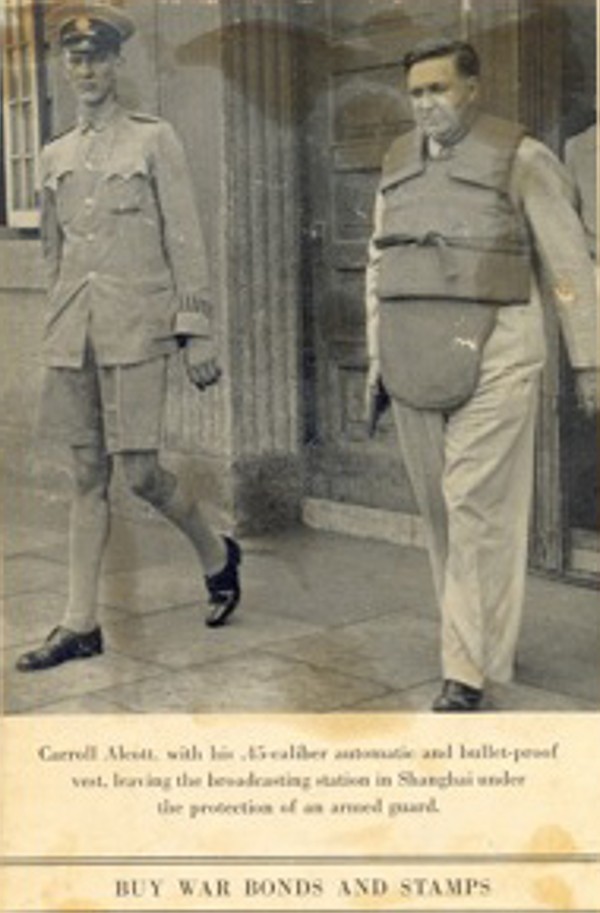

Many of the most popular radio broadcasters in Shanghai, such as the American journalist Carroll Alcott, maintained a strong anti-Japanese narrative. Alcott was so effective that the Japanese attempted to jam his transmissions. One United States intelligence report seen by Wasserstein called Alcott the “most useful propagandist in Shanghai” and he lived with the almost daily threat of kidnap and murder. He was obliged to travel with a bodyguard and wear a bulletproof vest.

Wasserstein describes the American journalist, radio broadcaster and former criminal Don Chisholm, who founded a gossip magazine called Shopping News. Through his popular periodical he not only exposed the dirty secrets within the expatriate communities to prurient local readers but also used blackmail as a revenue stream, by offering to retract or withhold the most shameful information about high-profile figures for a substantial fee. One of his many victims was thought to have been a self-styled Indian aristocrat called Princess Sumaire, who the Shanghai Municipal Police officially noted was “a follower of the lesbian cult” and “probably a nymphomaniac”.

Germany had been building its propaganda capability in Shanghai since late 1939 but the arrival of von Puttkamer in 1941 raised its game. His mission was to organise a German propaganda office to broadcast the message of Adolf Hitler’s government to East Asia and beyond, so XGRS was key. He established the ambitious German Information Bureau in the penthouse suite of the Park Hotel and later in a villa next to the church in the German concession. Bespectacled and animated, he could often be seen around Shanghai with his large Korean bodyguard and small dog. While his wife and children stayed in Europe, von Puttkamer “had a girl secretary and travelling companion who kept him happy in China”, as another allied intelligence report put it.

Early British propaganda efforts were even more clumsy. When the rousing anti-German movie Confessions of a Nazi Spy (1939) was shown by the British authorities at a Shanghai cinema, Chinese viewers were so impressed by the sight of stormtroopers goose-stepping into Czechoslovakia, they cheered their support. Later, XMHA and XCDN transmitted BBC dramas such as The Shadow of the Swastika and speeches by British prime minister Winston Churchill as the war of words raged across the Shanghai airwaves.

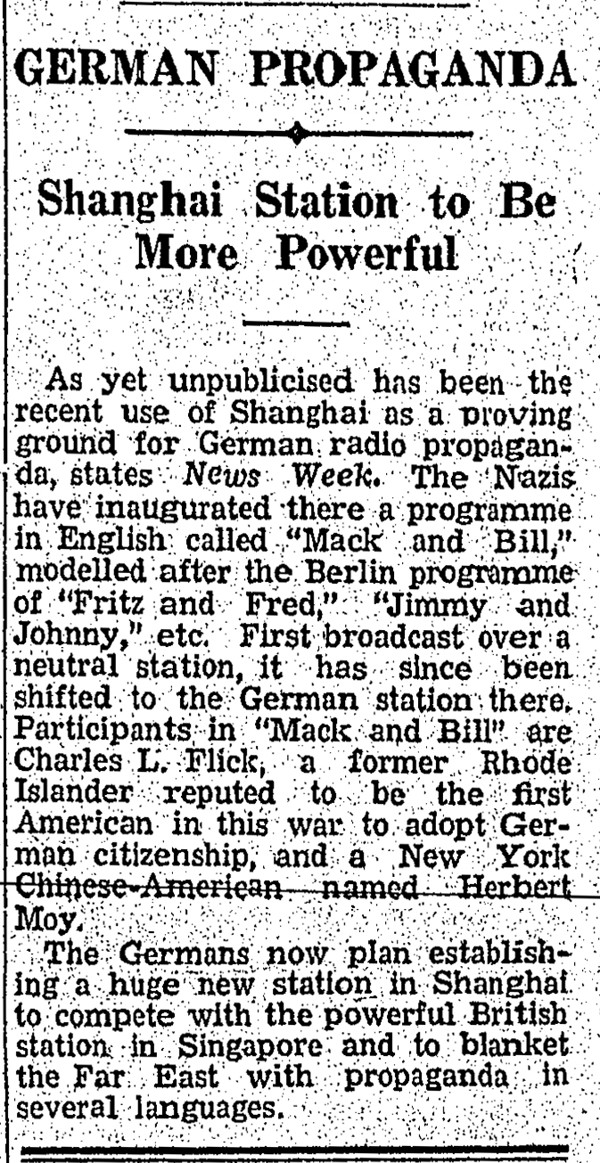

Under the stewardship of Carl Flick-Steger, a suave and experienced German-American who had been educated at Brown University, in Rhode Island, and who was also to be a witness in the Johnston/Gracie case, XGRS quickly outshone all competing media and propaganda outlets.

“This German station is considered the best and most efficiently run in the Orient,” a Shanghai Counter Espionage Summary, dated August 12, 1945, and published by US Intelligence services, would state.

Australian John Holland, a former car salesman in Singapore, was another popular XGRS personality.

The three British voices heard on the station included those of Johnston and Gracie.

“My impression is that these three were chancers rather than ideological collaborators,” says Wasserstein.

Johnston would claim in court that he’d been born in Shanghai and was actually Irish; he adopted the pseudonym Frank Kelly on air. He had served time in the San Quentin penitentiary, in the US, and was well known to the intelligence services. He started working as a broadcaster with XMHA but Flick-Steger headhunted him for XGRS.

Gracie, who broadcast as the recalcitrant working-class Scottish agitator Sergeant Allan McIntosh, would tell the court that he had been gassed on the Western front during the first world war and made a “king’s corporal”. He worked to support a Japanese wife and child, he said, who were repatriated to Nagasaki while he was interned for a period at the Haiphong Road Camp. Upon release, he said, the Japanese told him his family would be returned if he kept broadcasting for the Germans. They weren’t and it’s possible the Scot never saw his wife and child again.

Gracie had had an earlier brush with Hong Kong justice. In 1937, he had been brought before the Central Magistracy, charged with being destitute in the colony.

The third British broadcaster on XGRS was an urbane former Indian Army officer called Robert S. Lamb, who ran the English-language magazine The Cathay Cosmopolitan, which was 49 per cent-owned by a leading member of the local Nazi party. Using the catchy pseudonym Billy Bailey, he replaced Johnston on XGRS after the latter had had a run-in with the Japanese and been briefly imprisoned.

Lamb was brought to Hong Kong for prosecution with Johnston and Gracie in 1947 but the charges against him were dropped for reasons unknown. He was held in Hong Kong for months while the colonial authorities agonised over what to do with him. Eventually, he successfully sued the government for wrongful imprisonment.

There was a tectonic shift in the battle of the Shanghai airwaves on December 8, 1941, when, coinciding with the invasion of Hong Kong, the Japanese took control of the foreign settlement without any significant fighting. The days of the free press were over and the Japanese were now able to exert a throttling grip on the Shanghai media. Although nothing could be broadcast or printed without the approval of the new masters, there was a notable absence of resistance on the part of the media set.

The Shanghai Times was taken over by the Japanese embassy on December 9. Editor and proprietor E.A. Nottingham, already considered a traitor by the British community for the pro-Japanese line his publication took and later described by the Americans as a collaborator, stayed on with his staff and was paid to publish propaganda. Irishman Thomas A. Butler became editor of The Shanghai Evening Post under Japanese control and was a regular broadcaster on the now Japanese-controlled XMHA. According to American reports, he was “considered untrustworthy and the worst of the Japanese collaborators”. Chisholm started broadcasting for a Japanese station, too, and the same reports state “he is looked on by Americans as their number one traitor”.

As Wasserstein reveals, it wasn’t just journalists and broadcasters who exchanged the chilling prospect of brutal internment in the Haiphong Road Camp for the relative luxury of working for the Axis powers.

“Quite early in the Pacific war, the British authorities noted a disturbing prevalence of collaboration among their citizens in Shanghai,” says Wasserstein.

Commercial enterprises carried on trading, public utility employees stayed in post and even the British-staffed Shanghai Municipal Police maintained law and order for the Japanese.

As Wasserstein notes, companies such as Butterfield & Swire, Jardine Matheson and the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank were all open for business as usual in Japanese-occupied Shanghai, while members of the Allied armed forces were losing their lives in the Pacific war.

“The police were acting in accordance with orders. The businessmen were acting in accordance with what they understood to be the interests of their shareholders,” says Wasserstein.

Perhaps no company was more guilty of economic collaboration than the Kailan Mining Administration. Chief manager Edward Jonah Nathan OBE stayed at his post with the Sino-British coal mining enterprise together with 71 of his senior British staff, all of whom received salaries as so-called advisers, producing coal for the Japanese war effort. On eventually being replaced by a Japanese national in February 1943, the British manager received an official letter of thanks from Japan for his “great devotion”.

When the Allied civilians were liberated from Haiphong Road Camp by US Forces in 1945, there was a great deal of resentment directed towards those who had enjoyed a more comfortable war, and someone needed to be made an example of. Given that both had been interned at various points during the war, it’s difficult at first to see why, in light of widespread collaboration and criminality, Johnston and Gracie should have been singled out for prosecution.

“Gathering evidence and establishing a solid legal case was difficult; there were other priorities,” suggests Wasserstein, and perhaps high-profile radio broadcasters were easy and obvious targets.

However, although the comprehensive Shanghai Counter Espionage Summary – some 37 pages listing 27 known propagandists in a who’s who of spies in Shanghai – includes the names of Flick-Steger, von Puttkamer, Moy, Chisholm, Holland (who appears to have spent at least some time in an open prison in Morotai, in Indonesia’s Maluku Islands, after the war) and Johnston, there is no mention of Gracie.

As news reached Shanghai of the Japanese surrender, Moy took his own life by slitting his wrists and then flinging himself out of a hotel window, but most of the Allied collaborators and propagandists emerged from the war unscathed. Nottingham, Nathan, Chisholm, Butler and Lamb all walked free and none of the companies that kept working were ever rigorously investigated.

In his statement to the Hong Kong court after he was found guilty of broadcasting enemy propaganda, Johnston said, “Everyone continued to work under the Japanese until 1944. Engineers in the Power Company and factories also continued to work although these places manufactured war materials for the Japanese. Chungking agents were arrested and shot in the streets by British Police officers, but they have apparently been forgiven. I can name at least 20 fat and well-clad collaborators.

“Money talks – money buys freedom and the best legal aid – money could bring witnesses by the score from Shanghai to prove to you that the three German witnesses are lying.”

In her book Wartime Shanghai (1998), Wen-hsin Yeh, a professor of history at the University of California, Berkeley, writes, “It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that race and class form the primary explanations for these differential outcomes.”

Johnston and Gracie, whose fates following their sentencing have proved difficult to trace, were perhaps scapegoats for a wider malaise.

Gracie, who remained defiant, had this to say in his final court statement: “It is very easy for the well-fed people holding darn good jobs and who have never served in the armed forces of the British crown to criticise my actions. If a man who goes out to battle for a living to save his wife and child from the gutter by working at a German broadcasting station is to be criticised, then I have nothing more to say.”