Tiger parents have the equation for their children’s success backwards; a Taiwan-born psychiatrist explains why

Brought up in Britain to excel academically by her Chinese parents but exposed to Western parenting too, Dr Holan Liang explores in a new book how to create the right environment for children’s self-esteem to bloom

It is a summer’s day in London, not that you would know it from the rain dribbling down the large windows of the cafe at Maudsley Hospital, Britain’s largest mental-health training institute. I am sitting with Dr Holan Liang, who sips a cappuccino while a baby at the next table cries intermittently, but loudly.

Liang seems unfazed by the piercing noise, which is perhaps not surprising given her day job. A child psychiatrist by training, her specialism at the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust is in paediatric neuropsychiatry: she is a consultant with its Community Neurodevelopment Mental Health team, and often involved in the treatment of autistic children.

In addition to this busy job, Liang works in private practice at the Effra Clinic, a boutique mental health facility in central London specialising in attention deficit hyperactive disorder and autism spectrum disorder, and has somehow found the time to write her first book, Inside Out Parenting, the bold subtitle of which reads: “How to build strong children from a core of self-esteem.”

“It is not the ultimate parenting manual,” says Liang. “It is about issues that are out there, and how I have struggled to answer those questions for myself. I don’t think there is a right or wrong way. You have to find that path for yourself. What I think is important is for parents to be thinking about it constantly. But I do think I think about it more than the average parent.”

Some of the arguments in the book might raise eyebrows, not least for academically focused parents. Liang argues: “Social skills come above intelligence. Social skills are one of the fundamental layers for success. Intelligence is further back. I work with children with autism, which is why I am skewed to thinking about social skills.

“You see children with high functioning autism who have amazing ability but can’t get themselves dressed and to work on time. What is the point of doing PhD level maths if you can’t function in day-to-day life?”

Liang explains her recommendation using two contexts. The first summarises recent scientific research to argue that “gene-environment interaction” is the most important means to maximise a child’s intelligence. Or, to quote Liang’s title, a balance of inside and out.

Liang’s implicit warning is that nature, while important, can only achieve so much: geniuses need helpful environments to reach their potential. At the other end of the scale, nurture can only go so far. “If your child’s IQ potential is between 40 and 80,” she says, “however good the environment is, you can’t get them up to 100. They are going to be in the learning difficulty range.”

The second context is culture. What works in Hong Kong or Taiwan might not translate to London, and vice versa. “There are lots of parenting books which advocate practises from across the world, but they are misleading,” argues Liang. “Your genes are only successful in certain environments. In an Eastern environment, if you want to succeed you have got to get good grades. In the UK, where that is not necessarily the case, that is not the optimal model.”

In an Eastern environment, if you want to succeed you have got to get good grades. In the UK, where that is not necessarily the case, that is not the optimal model

As she frequently does in the book, Liang includes personal observations. For example, when she shares memories of her own “tiger parents”.

“In terms of my own childhood, the ‘push’ side my parents gave me lead to academic success, without a doubt,” she says. “But I could also see that a lot of it was quite extreme. I could also see that the Chinese tendency to put social skills as a lower priority [than academic ones] is detrimental.

The moral of this story, as with so many others in the book, is that it’s important to have both skill sets.

Meeting Liang in person, it’s clear that Inside Out Parenting is a reflection of her own personality, which can be academic or personal, forthright or funny, self-effacing or generally optimistic. Liang emphasises parents’ centrality in their children’s imaginations by recalling her conviction (shared by her two sisters) that her father was better looking than pop star George Michael.

Is that true? “Oh god, yes,” she laughs. “Parents are idolised.”

Elsewhere, Liang’s candour, both in conversation and writing, can be mildly unsettling. When I ask whether she had any qualms about writing a parenting guide, which can sometimes come across as judgmental, Liang replies: “No. I thought, ‘What are [readers] going to think of me? Are they going to think I’m a terrible doctor, if this is what I do with my children?’”

She offers a hair-raising example. “The part when I try and lock my daughter in her room,” she says. “Are the social services going to come and arrest me? ‘How can you be a child psychiatrist if you do this?’”

The book puts the scene into perspective. Liang had been writing about using a “naughty mat”, to provide breathing space for her daughter, Molly (not her real name, Liang being protective of her children’s privacy), who, according to the book, is prone to tantrums. When the mat outlived its usefulness, Liang transferred Molly to a “naughty bedroom” to calm down. As this process could take 45 minutes, and Molly was smart enough to open her door, Liang occasionally locked her in, and waited in the hallway outside.

What would Dr Liang have said if a client had admitted to effectively imprisoning an angry child? “Oh god,” she says, with a sheepish giggle. “I have would have said, ‘Surely there are better ways, behavioural management strategies you could try beforehand?’”

The lesson to be drawn, of course, is that parenting in theory is different from parenting in practice. And Liang is clear which has proved most beneficial for her. “I don’t think being a child psychiatrist has affected my parenting,” she says. “But becoming a parent has really affected my being a child psychiatrist. I am so much nicer and more sympathetic.”

Such geniality has been hard-won. The seeds of Inside Out Parenting were sown during a period of personal and professional instability. While Liang never fails to come across as an impressively devoted mother, the compromises she made to achieve this did not come without pain.

“This book came from very dark times in terms of thinking my career was over,” she says. “When I was pregnant with my son, I had a three-way supervision with two professors. They were giving me glowing reports and I burst out crying. They asked why. I said, ‘Just because this is the end.’” Liang laughs. “You struggle on with one child and [work] is possible. With the second one, you know it is not.”

The dilemma feeds directly into the portrait of positive, engaged and active parenting advocated by her book. “When I had children, without a doubt they were coming first. My career was doing really well and could have taken off. But for me, children come first.” The resulting thesis can be summarised in one basic sequence of cause and effect: LOVE (parental) → ESTEEM (child) → ACHIEVEMENT (child, and possibly parent, too: academically, financially, professionally, personally).

I took Amy Chua’s book with a pinch of salt because I had had a very positive experience of tiger parenting

By love, Liang means committed, consistent and demonstrative affection, interest and participation in a child’s life. Although such prioritisation sounds selfless, she explains that everyone benefits in the long-run.

“The investment you give now with your family will last your lifetime,” she says. “Because I have spent time with them in their childhood, I actually like my children as people. If I had a choice between spending time with them or my friends, a lot of the time I would want to spend time with them. They see that you genuinely value them, and that’s where the self-esteem comes from.”

A crucial by-product of this intimacy is that parents get to know their kids, which enables them to make informed decisions about everything, from which school will suit them best to which extracurricular interests they will enjoy.

Doubtless there are parents around the world throwing their hands up at the blazing obviousness of this line. But, drawing on her professional encounters with families at her clinics, Liang suggests that even the fondest of parents can be myopic when it comes to their children’s actual identities.

“They might say, ‘He does jiu jitsu at three o’clock, piano at four, clarinet at five,’” says Liang. “They can list activities, but they don’t know the inner workings.”

The doctor is thinking here, in part, about the type of parent made famous by Amy Chua’s controversial bestseller, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (2011). In its most acute forms, this mixture of discipline and relentless academic drilling reverses the equation that Liang proposes for successful, well-adjusted children: ACHIEVEMENT (child) → ESTEEM (child) → LOVE (parental).

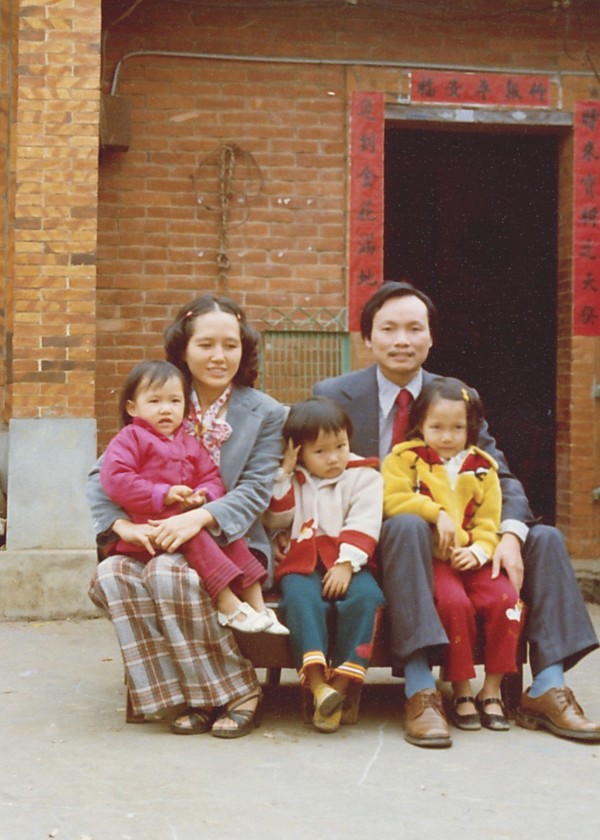

Liang speaks from personal experience: her own driven and ambitious parents moved from Taiwan to Britain when she was three years old. In the book, she recalls being drilled in arithmetic – she could recite the 12-times table before she was five.

On the eve of her A-level exams, which would decide which university she entered, “My mother took me by the shoulders, looked me in the eye and said, ‘You are our last hope to get a child into Cambridge University.’ No pressure then.” Liang did make it to Cambridge, where she studied medicine and experimental psychology.

“I took Amy Chua’s book with a pinch of salt because I had had a very positive experience of tiger parenting. You do come across tiger parents who have the pushy side without the loving side.” But, Liang emphasises, her parents’ strictness was always underpinned by unconditional affection, support and love, which bonds the family to this day.

If I had a choice between spending time with my children or my friends, a lot of the time I would want to spend time with [the children]. They see that you genuinely value them, and that’s where the self-esteem comes from

“My sisters and I are extremely close to my parents,” says Liang, before revealing that her middle sister gave up a successful career in the United States to be closer to her parents in London. “All of us would have been willing to give up our careers to be close to our parents. Family always comes first.”

Aspects of her tiger parents endure in Liang, who describes her own methods as “tigger parenting”. She has driven both her children to excel academically, with particular emphasis on maths and science, and urged them to pursue extracurricular pursuits, occasionally against their wills: piano and ballet in the case of Molly; soccer in the case of D (the letter a play on the Putonghua for “little brother”). In both cases, Liang insisted that participation was mandatory until a certain level of achievement, at which point Molly and D were allowed to decide whether to continue or give up.

Molly, for example, was compelled to take piano lessons until she passed grade three. “Because she is good and people tell her she is good, she has her own incentive to carry on,” Liang says. “It’s about getting children to a point where they have mastery. They know what it’s about, and whether they will enjoy it or not, and they can make an informed decision. If that is against what I would want, so be it. They live with the consequences.”

Liang acknowledges that this methodology is a fusion of her Taiwanese parents’ approach and her experiences growing up in Britain. “I felt I was in a good position having had exposure to both Western and Eastern parenting, so I could pick and choose,” she says.

Liang’s father left Taiwan to undertake a PhD at the University of Swansea in the 1970s. “In Taiwan, then, it was very prestigious to study abroad.” Liang’s mother arrived later, bringing with her three young children on what was her first plane journey. Was Wales in the ’70s a culture shock?

If you make parenting gender-neutral, and men say, ‘I want to work three days a week,’ then institutions will need to change. And they will change.

Yes, Liang says, but adds, with some embarrassment, that she only considered the problem properly when writing her book. She does recall the melancholy occasion when her mother made sushi for a street party celebrating Prince Charles’ wedding to Diana Spencer. Sparing neither effort nor expense, Liang’s mother travelled to London to buy the requisite seaweed. At the end of the festivities, she was devastated when no one had touched a single piece.

“Now, in London, if she brings sushi it’s gone in seconds. I remember my mum crying because no one even tried it.”

The Liangs decided to remain in Britain, not out of design – her mother was desperate to return to Taiwan – but, with some irony, because of education and culture. By the time her father had completed his studies, and won his dream job as a lecturer in Taiwan, his three daughters were unable to speak Chinese with any fluency, and unable to read it at all.

“Going back to the Taiwanese system, which was all academic based, if you can’t read or write, you will go to the worst schools and never make that jump back up,” says Liang.

In the book, the writer suggests that cultural dynamics of a different sort played a similarly crucial role in the success enjoyed by all three sisters: the absence of a brother. Would she have enjoyed similar success if there had been a Liang son?

“I don’t think so,” she says. “I know [my parents] would have behaved differently. If there had been a boy, he would have been given everything – all the attention. He would have been the one encouraged to do well academically. Certainly among my Taiwanese friends, the ones that have been the most successful are the ones without brothers.”

Gender is similarly prominent in determining Liang’s ideas about parenting. “One of my aims in this book is that we should start eradicating ‘mother’ and write ‘parent’,” she says. “Even if advice is gender-neutral, when you use the word ‘mother’ then a father picking the book up feels a bit alienated.”

And yet Liang is as vulnerable to “the unconscious gender bias” as the rest of us, admitting, “When I read back, I saw I had often written ‘mother’ by mistake and had to go back and take out every one.”

Such gender-neutrality is not advocated for reasons of political correctness, but to address the rapidly evolving challenges faced by parents.

“The time when you have children is often the time when your career is about to take off,” says Liang, adding that she turned down prestigious full-time positions in the knowledge that no London teaching hospital would meet her newfound requirement of working three days a week. “If you position yourself where your family comes first, those are the choices you go for.”

Liang acknowledges her own privilege in being able to step back from work. Her husband’s job in banking allows flexibility while funding their life in London’s exclusive, expensive Hampstead village. Nevertheless, Liang challenges the assumption that balancing work and parenthood should be an either-or proposition: choose family or career, but not both.

“I don’t want to have it all. I just want a bite of both cakes,” she says. “I don’t want the whole cakes. Just a bite.”

Flexible working practices are often impossible in a 21st-century job market that demands total commitment. Liang recalls her husband arguing that, in banking, his presence in the office was a given. Liang’s counter-attack points to a revolution in British medical practices. As a junior doctor, she worked 96 hours a week, a punishing and dangerous schedule that since 1998 has been halved by the European Work Time Directive.

“You have surgeons scrubbing in and out in the middle of theatre,” Liang says. “If it is possible for two doctors to work a case, there is no reason why two or three people can’t work a business case.”

The problem, the doctor insists, is that “companies at the moment don’t have the will. ‘It is a competitive job market. If you are not willing to work the hours, we will just get somebody else.’” But, she continues, “I don’t think there will be realistic change until the [parenting] problem is a universal one, not a woman’s problem. If the entire job market says this is unacceptable, then the institutions will have to change.

“If you make parenting gender-neutral, and men say, ‘I want to work three days a week,’ then institutions will need to change. And they will change. It will be a tipping point. It is a staffing problem. ‘Hang on: we can’t get anybody, male or female, if this is how things are run.’”

In this respect, Inside Out Parenting is Liang’s attempt to foster a revolution. The good news is that her husband has been persuaded, up to a point. “He said himself, ‘If I am out of the office because I’m in New York with a client, there is no problem. If I am out of the office because I am looking after my child, it is suddenly impossible.’”

The bad news is that if the status quo persists, everyone loses out: not just parents and children, but companies, too.

“I have friends with excellent degrees and now they are housewives,” says Liang. “They were really good at their careers but once you have children it is impossible. The country is losing. It is very short-sighted.”

The photographer arrives to take Liang’s portrait, if the rain will allow. I ask a final question before she braves the downpour. What advice does she have for parents who are facing the same potentially dark times she did? She draws again on her own experience.

“I will be very happy, I am sure, that I took this time out now for my children,” says Liang. “There will come a time when I can build up [my career] – if not in academia or clinical medicine then in something else. This is just a flashpoint in your life. The decisions you make now about your career in 10 years’ time may be insignificant.” She pauses. “But they won’t be insignificant for your children. They will be a lifelong imprint.”