Kim Jong-nam’s accused killers: North Korean puppets or cold-blooded murderers?

The women on trial for killing Kim Jong-un’s half brother – their lives, lost hopes and how they were lured into the plot

When Kim Jong-nam was a boy, his father, the dictator of North Korea, sat him on his office chair and said, “When you grow up, this is where you’ll sit and give orders.” If the child had fulfilled that promise – if his half-brother Kim Jong-un had not ultimately usurped his throne – he would have tyrannised 25 million people. His pudgy finger would have caressed the launch buttons of nukes. The United States and China would have debated how to manage him.

But as he glanced up at the departures board in Kuala Lumpur International Airport on February 13 last year, the jostling crowd ignored him. He had become just another balding and overweight 45-year-old, in this case one heading for his home in Macau.

As Kim Jong-nam sauntered towards an AirAsia self-service check-in kiosk at 8.59am, an Indonesian woman, in stylishly torn jeans and a grey sleeveless top, slipped out from behind a pillar. She covered his eyes as if playing peekaboo, and then wiped her hands over his mouth, leaving an oily smear.

“Sorry. Sorry,” she answered, before disappearing into the crowd.

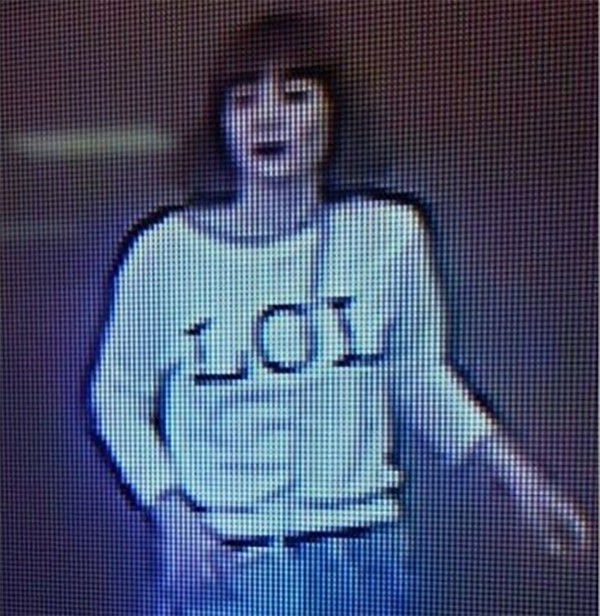

A second later, a Vietnamese woman wearing a white jumper emblazoned with the letters LOL threw her arms over his shoulders and rubbed her hands across his face. She apologised, too, before hurrying in the opposite direction of the first woman.

The liquid that the women had applied was already seeping into Kim Jong-nam, jamming his muscle receptors in the “on” position, causing the muscles to constantly contract as if struck by cramp. The compound was VX, a chemical weapon that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US calls the “most potent of all nerve agents”, and which the United Nations classifies as a weapon of mass destruction.

Kim Jong-nam started towards a bathroom, but lost his only chance to wash off the toxin and survive when he re-routed to a nearby information desk. “Very painful, very painful,” he complained in English. “I was sprayed liquid.” By the time an attendant led him to three policemen, who were chatting rather than monitoring the crowds, the Korean could only groan incoherently as he jabbed at his face with both hands.

A bored-looking officer guided Kim Jong-nam to the airport medical clinic, but after about three minutes of walking, his knees had stiffened and his feet dragged. The nerve agent was relentlessly stimulating his muscles, and his respiratory system and heart already neared exhaustion.

In the fluorescently lit clinic, the Korean collapsed into a black pleather chair. His indigo T-shirt rode up his belly and a golden pendant, engraved with a portrait of his wife and son, surfed his heaving chest as he laboured to breathe. As his lungs contracted, never relaxing to allow air out, nurses fixed him to an oxygen tank. When he was stretchered to an ambulance, paramedics discerned a faltering heartbeat. But en route to the hospital, it flatlined. He had lasted little more than 15 minutes from the time of the poisoning.

Earlier in his life in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), to give North Korea its official name, Kim Jong-nam had bodyguards watching his back. He was the firstborn son of despot Kim Jong-il, living in a mansion staffed by 100 servants and 500 guards, and sat on a direct path to ruling the secretive nation. But after his father acquired a new mistress who bore two more sons, Kim Jong-nam was dispatched to an exclusive private school in Geneva, Switzerland.

Still, his ascension seemed likely. On his 24th birthday in 1995, Kim Jong-nam was presented with a general’s uniform and was soon assigned posts in the secret police and the ruling political party. The state began cultivating the grandeur necessary for him to succeed his father.

Despite the incredible power that Kim Jong-nam wielded in North Korea, childhood friends described him as depressed, missing the freedoms he had become accustomed to in the West. He took luxurious vacations abroad whenever he could.

Kim Jong-il may have suspected that his son lacked the killer instinct necessary to run a dictatorship: he was eventually associated with lenient policies toward defectors and was assigned to manage the country’s information-technology systems instead of managing hit squads.

In 2001, Kim Jong-nam was arrested trying to sneak into Japan on a fake Dominican Republic passport bearing the alias Pang Xiong, meaning “fat bear” in Mandarin. During his three-day detention in Japan, he confessed that he had wanted only to visit Tokyo Disneyland. Consequent news stories of an immature heir served to humiliate Kim Jong-il, and reports of Kim Jong-nam’s diamond-encrusted Rolex and his female companions’ Louis Vuitton bags highlighted the regime’s extravagance while its people suffered famines.

Kim Jong-nam’s fall from grace was abrupt. Kim Jong-il immediately cancelled a diplomatic trip with his son to China. For at least a year, Kim Jong-nam did not return to the DPRK, and as he waited to be re-admitted to the North’s capital city of Pyongyang, his globetrotting eventually devolved into a debauched permanent exile in glitzy Macau.

Who would succeed Kim Jong-il remained hazy, even after the leader suffered a stroke in 2008. But those questions began to resolve themselves in 2010, when Kim Jong-un, the youngest son, was named to high military and political posts, passing over a middle son regarded by their father as effeminate. In 2011, Kim Jong-il’s death was announced and Kim Jong-un consolidated the power that birth and circumstances had put within his reach. While Kim Jong-un stood beside his father’s casket, Kim Jong-nam was conspicuously absent.

Soon thereafter, Kim Jong-nam critiqued his younger brother’s ascension in an email to a Japanese journalist, calling his half-brother a “joke to the outside world” and echoing doubts that many in the international community harboured about the new 27-year-old dictator. Kim Jong-nam predicted, “The Kim Jong-un regime will not last long.”

But Kim Jong-un displayed the ruthlessness of a natural-born tyrant: he had his mentor and main rival – his uncle – killed, reportedly used anti-aircraft guns to execute disloyal officials, and aggressively developed nuclear missiles capable of striking the US.

Kim Jong-nam should have known what was coming.

First, his funds from the regime were cut off. Then he had to start dodging physical attacks. In 2010, a DPRK agent in China was ordered to give a sack of cash to a taxi driver to stage an accident, but Kim Jong-nam never arrived at the scene. He ducked another assassination attempt in 2012, the same year he sent a letter to Kim Jong-un, begging, “Please withdraw the order to punish me and my family. We have nowhere to hide. The only way to escape is to choose suicide.”

But the next day, South Korean news agencies announced that Kim Jong-nam had been murdered. Reuters alleged that Malaysian officials had confused the two Koreas and notified the wrong embassy – a mistake the Malaysian government subsequently denied, but which would explain why the earliest reports about Kim Jong-nam’s identity broke in Seoul. When airport CCTV footage of the attack was leaked to a Japanese news outlet, the story went viral worldwide.

By the following morning, observers were noting that the two women, whom police had quickly captured, had not acted alone: at least four men, subsequently described by South Korea’s intelligence agency as DPRK spies, had orchestrated the attack. Two days later, the number of suspects that police had identified had risen to seven. A North Korean with a doctorate in chemistry had already been arrested.

A little before midnight four days after the attack, the North Korean ambassador to Malaysia confronted a siege of reporters from around the globe outside the mortuary housing Kim Jong-nam’s body. He protested that “Kim Chol” was a DPRK citizen, and he accused Malaysia of trying to “besmirch the image of our republic”, possibly in collaboration with South Korea. He also demanded the corpse.

The diplomatic stand-off unravelled into an international crisis. The Malaysian government expelled the North Korean ambassador. In response, Pyongyang barred all Malaysians from leaving North Korea, essentially holding them hostage. Nuclear-disarmament talks between the US and the DPRK broke down. China rebuked its neighbour by turning away coal imports, a linchpin of the North Korean economy. It seemed that the assassination and simultaneously escalating confrontation over Kim Jong-un’s nukes could explode the decades-stalled Korean war into a global conflict.

A month and a half later, Malaysia caved in to free its citizens, turning over the corpse and allowing three suspects hiding in the North Korean embassy to fly home. This left only the two imprisoned women to face justice. Under Malaysian law, they will be executed by hanging if convicted of murder.

As the crisis churned on, however, the identities and motivations of the women remained mysterious. How had two twenty-somethings from rural Southeast Asian villages – the Indonesian said to be a prostitute; the Vietnamese working as an escort – become involved in an international assassination plot?

The answers had likely been hidden in plain sight by the North Korean spymasters, and their revelation was designed to make the global order tremble.

The two women had been identified from CCTV footage with ease. The Vietnamese woman’s LOL jumper proved especially easy to track through the grainy footage. Catching her was simple, too: Doan Thi Huong, then aged 28, was arrested the day after the killing, when she returned to the airport. Her early dreams of celebrity having been dashed when she lasted just 20 seconds on Vietnam Idol, she had ended up working as an escort in Hanoi, where she was recruited by an undercover North Korean agent, according to an internal report by the Vietnamese government.

At about 2am on the morning after the murder, Malaysian police marched through the dank hallways of Kuala Lumpur’s Flamingo Hotel, in which stained, springless mattresses leaned against walls to air out during the day. In a third-floor room, the second alleged assassin, 25-year-old Indonesian Siti Aisyah, had just finished servicing a Malaysian client when officers burst through the unlocked door.

From the CCTV footage, Huong’s and Aisyah’s guilt seemed clear until, under separate interrogations, they both explained that they thought they had merely slathered Kim Jong-nam with a harmless liquid for a hidden-camera TV show. The chief of police scoffed at the idea, declaring at a news conference, “The two female suspects knew the substance was toxic.” He pointed out that immediately after tagging Kim Jong-nam, they had run to airport bathrooms to scrub poison from their palms. But the two women were adamant: they had not meant to hurt anyone, let alone to kill.

Although both women’s lives followed remarkably similar arcs of disappointment, from impoverished hamlets to seedy nightclubs to prison cells, it was Aisyah’s footprints that I tracked across Asia because, having lived for three years in Indonesia, I had met dozens of vulnerable migrant women who could have suffered her fate, and felt there was likely to be more to the story than Malaysian police had reported.

The truth was more complicated than I ever could have imagined.

Like Hoang, Aisyah has been recruited by a representative for the North Koreans who I later tracked down, in her case at about 3am on January 5, 2017, outside a notorious bar in Kuala Lumpur. On paper, she worked as a masseuse in the Flamingo Hotel’s spa, but when I visited in July last year, a worker immediately asked, “You want to sleep with a Thai or Indonesian girl?” Later, one of Aisyah’s friends laughed when I said I’d heard she had given massages there, declaring, “She was totally sex.”

Some evenings, Aisyah would finish at the spa, get dressed up and take a taxi downtown to Beach Club Cafe. In front of the kitsch, surf-themed spot that serves rubbery pizzas to expatriate families, she joined dozens of skimpily dressed Indonesian and Vietnamese women smoking and checking their phones. Then, at 10.30pm sharp every night, as the last mothers shepherded their children to bed, the club music began to blare, a fog machine was deployed and working girls catwalked in. While small sharks circled in the aquarium above the bar, manicured fingernails alighted on the shoulders of pot-bellied men from America, Japan and beyond.

Three staff members recalled seeing Kim Jong-nam, who was known to frequent prostitutes around the world, occasionally visit Beach Club Cafe. Five employees told me they recalled Aisyah prospecting there.

On the fateful night of her recruitment, Aisyah was alone when she pushed past the bouncers and out onto the street – it hadn’t been a successful evening. But from the queue of taxis, one 40-year-old cabby, named “John”, whom she already knew, called her over. A man had asked him to find girls he could film smearing lotion on the faces of strangers.

The request was only slightly strange: drivers regularly acted as go-betweens for tourists and prostitutes. “B”, a close friend of John and Aisyah, who also worked Beach Club Cafe, told me they thought John’s client wanted to make a porn film.

The proposed payment – more than US$100 – overcame any reservations Aisyah might have had. At the spa, her share of each trick amounted to just US$15, with the rest taken by her bosses. She had started freelancing because she could earn triple that on her own, and she helped support her family in Indonesia. As B said, “She was always talking about working for them.”

Her dream was to build a house in her native village and live there with her family, but Aisyah had never been skilled in business. “She always sold herself too cheap,” B recalled. “She was a beautiful lady and could have asked for more. But unlike a lot of other girls, she would never choose her man. She’d just sit in the corner and wait for anyone to approach her. A bad character or a monkey face, it didn’t matter if they had money.”

Less than seven hours later after they met at the Beach Club Cafe, when John picked up Aisyah, she was dressed in tight jeans and a red turtleneck sweater, which exposed her hourglass midriff. Smiling, she revealed braces on her teeth. She looked younger than her years.

At the upscale Pavilion Kuala Lumpur mall, among boutiques for the likes of Dior and Hermès, John introduced Aisyah to “James”, a handsome 30-year-old who claimed to be Japanese. Aisyah told him her name was Nidya, an alias she often used in Malaysia (even friends such as B would not learn of Aisyah’s real background until her mugshot appeared on TV).

James could not speak Bahasa Indonesia or Bahasa Malaysia, and so they communicated in choppy English, occasionally resorting to Google Translate for support. James explained that he was producing a hidden-camera comedy show, which would be shown on YouTube in China and Japan.

While in the mall, James directed Aisyah to rub a baby oil-like substance on the face of a seemingly unsuspecting Vietnamese woman while his smartphone recorded the action. Nothing seemed strange because everything was handled so publicly, and James insisted that Aisyah apologise after slathering her target.

Later that morning, they hit another mall, and Aisyah was paid again. When James suggested they make a video at the airport the following day, she happily agreed – she was, after all, earning more in minutes than she usually made in a day. And besides, a friend would later tell me, she had always dreamed of being an actress.

The only peculiarity that John ever noticed about James was that every time he called, his phone number had changed. B suspects that John did not act on this minor concern because he did not want to endanger his finder’s fee, and minor secrets were expected in their street-hustler world.

John had expected to continue fixing, but Aisyah told him that she wasn’t going to meet James again. Perhaps, B speculated, she did not want to cut John in on the money. But actually, for the next four days, Aisyah was completing two hits a day with James – it was training, she thought, to become a star.

Aisyah was born in 1992, in Ranca Sumur, a rural hamlet 120km to the west of Jakarta. Ranca Sumur’s 500 or so inhabitants raised rice and water buffalo, and Aisyah grew up scouring the nearby forest for firewood, bathing in streams and catching crickets, skewering them on bamboo slivers and roasting them over coals to be eaten as a snack.

She was named after the Prophet Mohammed’s favourite wife, and neighbours remember her as a quiet and religious girl. She usually arrived 10 to 20 minutes early for services at the terracotta-tiled mosque because her father often sang the call to prayer. At the age of nine, she put on a headscarf to attend the town’s newly opened religious school, which today is sponsored by a hard-line Islamic organisation identified by many experts as a terrorist group.

Aisyah’s education ended after sixth grade – Ranca Sumur had no middle school – and she spent her days helping her father, Asria Nur Hasan, chop ginger and turmeric. Then Asria would balance 20kg sacks of the spices at each end of a bamboo slat laid across his shoulders and flip-flop through country markets hawking his wares.

Aisyah might never have looked beyond the paddies surrounding her home if Jakarta, the Indonesian capital, had not been exploding into a modern metropolis of 30 million inhabitants. Many villagers viewed city life as irreligious and dangerous, but not Aisyah. Her vision of a glamorous and cosmopolitan city was shaped by what she glimpsed on TV. As Benah, Aisyah’s mother, told me, “Jakarta was her irresistible desire.”

She was named after the Prophet Mohammed’s favourite wife, and neighbours remember her as a quiet and religious girl

When Aisyah was 14, a relative arranged work for her at a small sweatshop in Jakarta, and her world shrank to three pasteboard-walled rooms stuffed with sewing machines and mountains of cloth. She laboured 13-hour days for US$50 a month, sweeping floors and snipping untamed threads from knock-off designer dresses. The steam from an industrial iron she wielded to package each dress turned her unventilated corner into a hellish sauna. But she could only stare at the factory’s single faraway window barred with rusted iron. The bosses were known for keeping the door locked, so she rarely escaped.

Perhaps a kilometre away, at a multi-storey mall, rich Jakartans sipped Starbucks coffee. But, as many migrants discover, moving to the city does not necessarily equate with realising one’s dreams. As one young man working in Aisyah’s former sweatshop told me, gesturing to the mound of fabric scraps he slept on as a bed, “City life looks nice on TV, but then you live like this.”

The sweatshop’s neighbours remembered Aisyah as a mousy, chubby kid who was too shy to chat, but they began gossiping when she started walking to the market with the sweatshop owner’s son, Gunawan Hasyim. The two married when Aisyah was 16; a baby boy was born soon afterwards.

By 2011, the sweatshop was struggling, and Gunawan sought his fortune in Malaysia, where he waited on tables and Aisyah worked as a shopgirl. For Aisyah, Kuala Lumpur must have seemed like a bizarre version of Jakarta, sharing a language and culture, but being much wealthier and run on the backs of migrants. Indonesian NGO Migrant Care calculates that about 400,000 of its countrymen and women make a similar journey legally each year, and that 600,000 do so illegally.

In 2012, the young couple divorced acrimoniously after her husband accused Aisyah of infidelity, and she returned briefly to Ranca Sumur with their son. Soon she left to work at a women’s clothing store on Batam, an island just south of Singapore.

Aisyah now had to earn money to help support her family, and life in the small village may not have suited her as well as it had during her childhood. “It is difficult for women who have lived abroad to return to their village,” explained Anis Hidayah, a co-founder and the executive director of Migrant Care. “They may not have any way of making a living, and they have experienced having more freedom of expression.” Certainly, Aisyah wanted a more modern life for her son, and she relinquished custody to her former parents-in-law in Jakarta so that he would be educated in the city.

Scrolling through Aisyah’s Facebook posts from the subsequent four years is like watching a time-lapse of her transformation from ingénue to fille de joie. At first, she decorated her wall with awkward selfies, which showed her trying on different clothing styles, including veils. Gradually, however, the religious vestments were replaced by lacy black garments.

Instead of posting about how Allah had helped her endure heartbreak, Aisyah humble-bragged about meeting girlfriends at trendy coffee shops. She grew thinner and began wearing striking make-up. By the time she returned to Kuala Lumpur in early 2015, she was posting pictures in which she fixed the viewer with come-hither stares.

At first, Aisyah was employed at a spa beneath the misleadingly named and down-market Hotel Grand Continental in Indonesia. In July, when I descended its urine-smelling stairwell to dungeon-like rooms, I was promptly offered prostitutes.

After just a few months, Aisyah moved to Hotel Flamingo, where she received a slightly improved salary. Eventually, she acclimated to her new profession, and she casually complained to B about single-customer days. Under the name “Kelly”, Aisyah appeared on Kuala Lumpur-centric escort website Haven4Men.com, showing off her braces with a smile and wearing contacts that coloured her irises blue, offering “blowjob, f***job, overnight” for about US$40.

Every evening, she heard the call to prayer echoing through Kuala Lumpur at the same time her father probably ululated across the paddies, “Come to prayer; come to success; God is the greatest.” Friends remember that she no longer answered the summons herself.

By early 2017, despite the happy-go-lucky facade she presented on Facebook, she was despairing of her life, and B said that Aisyah may have started taking meth to gin herself up to work. On her occasional trips home, she bought fried meatballs from street vendors for neighbourhood children and took her parents on holidays, but she could not bear to tell them the truth about the origins of her money. Every 30 days, when her tourist visa expired, she exited Malaysia, but always returned to Kuala Lumpur on a new one. The city had become her home.

After James enticed Aisyah with his too-good-to-be-true offer of salvation, they toured the luxury hotels and malls of Kuala Lumpur for five days from January 5, smearing oil and hot sauce on Chinese-looking men. Each prank was rewarded with another windfall.

According to Aisyah’s Malaysian lawyer, Gooi Soon Seng, before long, “Aisyah started telling James she was tired of her present career, and that she looked forward to the new life of being a star.” She bragged to acquaintances that she was going to be a celebrity. When a friend video-called Aisyah on her birthday and joked that she would soon outshine a famous Malaysian actress, Aisyah agreed, laughing and jauntily flipping her hair.

At least once, Aisyah asked to see the recordings of herself, but James told her the film was still being edited and, according to her cousin, wouldn’t let her see it because it would make her self-conscious.

Then, on January 21, James flew her to Cambodia for more “spoofing”, as they called it. “It was when she went overseas that she really started to believe she could escape her old life,” Gooi told me. James had even suggested she might spoof people in America.

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, James informed Aisyah that “Chang”, a 34-year-old “Chinese” man who spoke fluent Bahasa, would replace him. Chang led Aisyah through three practice sessions at the airport.

Aisyah said she passed the end of the month back in Ranca Sumur, with her family. She was there when Chang called, ordering her to return to Kuala Lumpur. Before flying out of Jakarta, Aisyah visited her son a final time.

On February 3, 4 and 7, Aisyah targeted victims at Kuala Lumpur’s airport under Chang’s supervision. He increased her salary to US$200 per hit. On February 8, Chang gave Aisyah US$4,000 to arrange a trip to Macau, where Kim Jong-nam lived. But the next day, Chang cancelled that plan – their ultimate target was already in Malaysia.

Two days later, Aisyah practised again at the airport. It was her 25th birthday, and when they were finished, Chang bought her a taxi ticket home. He told her that the next prank would be in a few days, on February 13.

Aisyah spent her last night of innocence at Hard Rock Cafe Kuala Lumpur, where her friends chipped in for a steak that cost two-thirds of her monthly salary at the sweatshop and, at a table laden with fruit-decorated cocktails, a mobile phone video shows one pal announcing, “And now the person next to me will become a celebrity.” Aisyah exposes her braces and bashfully tosses her hair. After her friends sing Happy Birthday, she blows out a lone candle on a cupcake-sized confection. Then they clubbed into the small hours.

By 8am, Aisyah was drinking coffee with Chang in a faux-colonial airport cafe offering an excellent view of the terminal. Soon, Chang led her behind a pillar near the AirAsia check-in kiosks. There, he told her that another woman would also participate in the prank and that she should leave after the second woman struck.

When Kim Jong-nam strolled into the terminal, Chang identified him to Aisyah by noting his grey blazer and dark backpack. Then, her lawyer says, he told her to look away and hold out her hand, likely while unwrapping something from a white plastic bag he had taken from his own backpack. An oily substance was slicked over Aisyah’s palm. She noticed it smelled like machine oil, whereas previous liquids had been odourless. Chang reminded her to apologise after striking and to leave quickly because the target “looks rich”.

As Kim Jong-nam approached, Chang ducked away and Aisyah advanced on her target. After rubbing the Korean’s face, she fled. Her first few strides were measured, but by the time she neared the bathrooms, she was running. There, as instructed, she washed her hands. Then she went shopping at a middle-class mall. By the afternoon, she was back at work at the spa, eagerly awaiting the next spoof, which would inch her closer to the life she dreamed of.

Weeks passed before Aisyah came to understand that North Korea had stage-managed every detail of her recruitment and the assassination of Kim Jong-nam.

James, Aisyah’s original handler, who had been introduced as Japanese, had really been a Korean named Ri Ji-u. He had met John, the taxi driver, while taking his cab, and then asked for his help in finding girls. According to B, John had first brought a Filipina to Ri, but she had demanded too much money. He also introduced the agent to a Vietnamese woman (who would later be Aisyah’s first practice target), before ultimately connecting him with Aisyah.

From that moment on, Aisyah had been steered by men who had been patiently preparing for their deadly task, carefully amassing assets across Asia. When Aisyah was flown to Cambodia, the man who took over from James was not named Chang, but Hong Song-hac. He was a Korean intelligence officer who had studied Bahasa at an Indonesian university, and then worked at the DPRK embassy in Jakarta. Huong had also visited Cambodia two days earlier, escorted by a North Korean agent with years of experience in Vietnam.

While Hong and Aisyah practised in Phnom Penh’s airport, three other spymasters who would later direct the murder had lurked nearby, too. The reasons for assembling the team are clear only to the North Koreans, but it’s possible they’d hoped to intercept Kim Jong-nam, who sometimes visited the Cambodian city’s casinos.

When I met Nam Sung-wook, a professor specialising in North Korea studies at Korea University in Seoul who had previously led a research arm with South Korea’s intelligence agency, he told me, “This murder was all part of a master plan.”

Citing contacts in intelligence communities, Nam explained, “From the moment Kim Jong-nam left Macau, the North Koreans tailed him. They had a group on his aeroplane. As soon as he arrived at the airport in Kuala Lumpur, another group followed him. They kept that surveillance up while he slept.” Even as Kim Jong-nam entered the terminal, he was being shadowed.

The liquid that Aisyah rubbed on Kim Jong-nam’s face was likely not fully constituted VX. Experts have suggested that VX2 was employed instead. “VX2 is made by dividing VX into two non-reactive compounds,” Vipin Narang, an associate professor of political science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology who holds two degrees in chemical engineering, told me. “What the women were likely doing was creating active VX on Kim Jong-nam’s face by each delivering their ingredient.”

This complicated method of poisoning Kim Jong-nam would have had advantages. First, the toxin would have been safe until activated. Even then, VX2 is not very volatile compared with other chemical weapons, making it less likely to affect bystanders or first responders. If VX2 was employed, it is unlikely Aisyah would have been affected because – striking first – she never would have been exposed to the second reactant. (Gooi dismissed reports that Aisyah vomited while taking a taxi from the airport.) And Huong may not have absorbed enough to make her ill, with only a minimal amount of toxin on the thick skin of her palms that was quickly washed off.

As Kim Jong-nam headed for the check-in kiosks, CCTV shows that at least five DPRK agents directed Aisyah and Huong throughout the cavernous terminal. Hong having escaped to the bathroom after dispensing the nerve agent, a North Korean lurked nearby to oversee Aisyah’s and Huong’s strikes. A third agent monitored the attack from the coffee shop. And as Aisyah and Huong fled after poisoning Kim Jong-nam, a fourth operative, later identified as the high-level spy likely responsible for the success of the mission, brushed past them and may have exchanged signals confirming the stunt had been successfully pulled off.

A fifth North Korean, pulling a wheeled case, eavesdropped as Kim Jong-nam spoke his last words at the information desk, complaining of pain and trying to explain the attack. As the dying man stumbled towards the medical clinic, the agent followed, one hand casually plugging his pocket. Through the glass walls of the waiting room, he watched as their target slumped into unconsciousness. He maintained his post as the victim was rushed to an ambulance.

It was only once the ambulance doors closed that Kim Jong-nam finally escaped the eye of the North Korea’s Supreme Leader – his own half-brother. Finally, he had the privacy to die.

Meanwhile, when Hong exited the bathroom, the black backpack and white plastic bag he had carried during the attack had vanished. He had also changed his clothes – only his shoes remained the same. With the four other agents, he cleared immigration. A high-level staff member from the DPRK embassy saw them off on flights pre-scheduled to depart immediately after the assassination. They took a circuitous flight path, circumventing countries that might have grounded their planes should the murder have been discovered while they were in transit.

By the time anyone might have guessed what had happened, they were already safe in Pyongyang.

“ The first four times Indonesian officials visited Aisyah after the arrest, she thought that being in jail was part of the prank,” said Andreano Erwin, the acting Indonesian ambassador in Malaysia, when I met him at his embassy just after Aisyah was picked up. Because she did not follow the news, she had no idea that anyone had died at the airport, according to her lawyer. For Aisyah, it had just been another prank. “The first time we visited her, she kept asking when she could leave the jail,” he said. “The second, she complained that she still hadn’t been paid for the last prank. The third time, she accused us of being part of the prank. The fourth time, we showed her a newspaper proving Kim Jong-nam had died. When she saw it, she started to cry.”

At the end of July last year, Aisyah was led into court, a policewoman gripping each of her arms and a bulletproof vest turtled over her traditional Malaysian dress. Through her lawyer, she has consistently claimed she was tricked and has pleaded not guilty. After the judge announced that the trial would start in October, she wept. “That’s when she fully realised how serious this was,” the acting ambassador said.

As Aisyah gained weight in a cell near Huong’s, she wondered how deep the North Koreans’ deception had penetrated. When confronted with pictures of Hong, she recalled that a man she had smeared in a hotel – two weeks before formally meeting her new puppeteer – bore an uncanny resemblance to the Korean. This suggested that targets struck during practice sessions could have been knowing participants all along, ensuring that “victims” would not contact police.

At first, Aisyah avoided communicating with her family from prison out of shame, but when she was permitted to call them during Ramadan, she begged, “Forgive me, body and soul.” When the call to prayer echoed through the prison five times a day, she submitted to the words of her father.

By late July, I had visited Kuala Lumpur, Seoul and Jakarta in my research. One evening in July, I found myself in Ranca Sumur, helping Aisyah’s parents unroll prayer rugs across their concrete porch for a village-wide ceremony for the woman. As we worked, her mother told me, “She was our little girl. We loved her more than our own lives.”

Malaysian police had founded their prosecution on the meticulous planning of the attack. The only evidence they had offered suggesting that the women had foreknowledge of Kim Jong-nam’s death was that they cleaned their hands after the poisoning, which, it was argued, showed that they knew they had used a toxin. However, both defence teams have claimed that the North Koreans told their clients to wash off the liquid without informing them what it was. (For his part, Aisyah’s lawyer does not concede that the airport surveillance footage shows Aisyah applying the deadly agent to Kim Jong-nam’s face; he says the prosecution must prove that’s what happened.)

And, as Gooi explained, Aisyah’s mental state at the time is crucial. “Under Malaysian law, it’s not murder if there was no intention to kill,” he said. “My client was tricked and thus lacked intent to commit a crime.” Gooi continued, “Aisyah didn’t even know the difference between South and North Korea.”

Aisyah’s friends and family also described her as naive. “Aisyah was just a village girl,” said B. “She had no idea what she was doing.”

Based on my research, the only hint that Aisyah knew the identity of the North Koreans was that before the murder she told a friend that she was going to become a star in Pyongyang, and later repeated this to a senior Indonesian diplomat, though both clarified she still believed she was participating in a comedy.

But, I explained to Aisyah’s parents, new evidence could emerge at the trial that disproved Aisyah’s ignorance and explained the forceful pursuit of a conviction. However, by February 28, the case having restarted after a break for Lunar New Year, the prosecution had brought no damning evidence about Aisyah’s motivations. A review of thousands of her WhatsApp messages, some with the North Koreans, in which some analysts had thought incriminating messages might be found, had instead showed no awareness of who her bosses really were.

Essentially, the case is founded on the careful choreography of the plot, while minimising North Korea’s involvement, as if trying to imply that Aisyah and Huong had planned the killing themselves. Observers have speculated that this prosecutorial strategy stemmed from a deal Malaysia made to bring the hostages in North Korea home and that the nation – embarrassed at having played host to the assassination – was now simply eager to punish anyone it could for the crime.

Ultimately, while following Aisyah’s trail, I have been haunted by the feeling of approaching but not quite reaching her. The closest I came was outside the court after her trial date was announced, as the wind from her racing police van flipped the pages of my notebook. But the window that would have let me see her was tinted black.

During the evening I spent in Ranca Sumur, about 50 men in Islamic formalwear knelt on the porch of Aisyah’s home and an imam dirged the Prayer of Mercy and Protection, silencing the croaking of night frogs. Incrementally, the men echoed him, until the whole community prayed.

The chorus intensified until the men were yelling and Asria’s face was transfixed between rapture and anguish as he shouted for his daughter to be delivered. What mattered to him was not the baffling geopolitical intrigue that had discarded her as a pawn. What mattered was that she returned home.

Looking at the fallout from the assassination, it is easy to buy into the idea that it was the botched work of an incompetent dictatorship. Throughout the mission, North Korean agents did not hide their faces from CCTV cameras, which can be interpreted as a rookie error.

But there is another possibility. As Nam of Korea University told me, “Pyongyang wanted to send a worldwide message by murdering Kim Jong-nam in this gruesome, public way.”

It has long been speculated that Kim Jong-nam had been sheltered by China and was viewed as a potential replacement should his half-brother be deposed, as he was known to be favourable to Chinese interests.

“Pyongyang wanted to horrify the rest of the world by releasing a chemical weapon at an airport.” Nam explained. By unleashing such weaponry in a place symbolically shared by the global community, North Korea was sending a warning. “Jong-un wants to reign a long time and negotiate as a superpower,” Nam said. “The only way to do that is to keep the world in fear of his weapons. He has a grand design, and this is part of it.”

Pyongyang has suffered no significant consequences from the assassination. The only people on trial for the murder are the two women, who Nam believes are not guilty. Prosecutors are expected to rest their case in April or early May. If the judge finds there is no case against the women, they will be freed. If he calls their defence, the trial will continue. Any appeal to higher courts would likely add years.

When I stepped out of Nam’s office into the neon-lit concrete canyons of Seoul, my skin prickled with a feeling of danger. Less than 60km away, North Korea had dug in more than 8,000 artillery cannons, which could rain 300,000 rounds in an hour on the southern city’s 10 million inhabitants. And that’s without counting the devastation that Pyongyang could wreak with its nuke-tipped ICBMs.

As I ran through Seoul’s government district to escape a storm burst, TVs blared that the DPRK had developed missiles capable of reaching Alaska. In late July, Pyongyang would test an even more advanced ICBM, capable of striking most of the continental United States. By August, President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un were menacing each other with threats of nuclear war.

In front of the monumental South Korean capitol, I realised that the spot where I stood was likely to be among the first cratered – and yet, South Koreans strolled past me on the sidewalk, carrying on as they must, their flimsy umbrellas barely shielding them from the fusillade of rain.

Doug Bock Clark’s first book, The Last Whalers, will be published next year. This story was originally published in GQ magazine.