From porn-star wife’s nether regions to Balloon Dogs: Hong Kong-bound Jeff Koons talks ‘plastic art’, selfies and Art Basel

The polarising perfectionist and blockbuster creator muses on the roles of viewer and creator ahead of an appearance at David Zwirner’s Art Basel booth

For an artist whose reputation is built on large-scale spectacle – think of those colossal canines, Puppy (1992) and Balloon Dog (1994), or the humungous-limbed Seated Ballerina (2017), or even his gigantic Bouquet of Tulips (2016) currently on offer to Paris, about which that city is being somewhat sniffy – there is little pizazz about the entrance to Jeff Koons’ New York workplace. On a chilly February afternoon, the West Chelsea street is full of sanitation trucks and storage spaces. “Private” states a blank door at the river end, plus a single clue: “Studio”.

Inside, it is deeply quiet. Koons is a hands-free – though emphatically not hands-off – artist. Many years ago, on a summer job, he damaged his hand in a machine and worried he would get arthritis. This, plus a taste for Marcel Duchamp, led him on the path of what he calls “the ready made”.

So the initial creative concept (say, toy rabbit – except shiny!) is his. The desire for perfect execution is his. But the physical work is done by assistants, of whom he has had many. Later, I ask for a current headcount, and he says, vaguely, “130”, but that cannot be quite right because the previous time we met, in November 2014, when he had a Gagosian show in Hong Kong, he gave the same figure and, according to news reports, he has cut back since then. That was the year he was No 7 on ArtReview magazine’s Power 100 list. Now he’s at No 54.

And yet when he arrives, he elects to conduct our conversation in public, at a work bench in the room of the five toilers. As we sit down, facing each other, something bothers him. There’s a nanosecond ripple of discomfort. He extracts a sheet of white paper from a nearby pile and places it down carefully, close to his right elbow. When I look underneath, it’s hiding a coffee-cup ring.

If you met him in the street – smiling, earnest, eager to convince you – you might think he was a missionary

In the same way, there’s a hiccup with the tape recorder and when that’s sorted, he says, “Are we starting now? The first part is off the record? I just want to be sure. Prior doesn’t exist?” But there is no prior – he has not said anything so far. Koons is such a perfectionist that even the pre-conversational surface needs to be as scuff-less, as polished, as possible. The stage is set; the audience is silent; the performance begins.

“Let’s start over,” he says.

If you met him in the street – smiling, earnest, eager to convince you – you might think he was a missionary. “Like Mormon,” I’d scribbled in my notes last time, shorthand for his clean-cut, gleaming-eyed fervour. When I had asked him if he was religious, he had replied, “Philosophical – I see life as trying to achieve transcendence.”

That’s one of his favourite words. Others include mythic, aesthetic, meaningful and biological, plus a list of high-cultural references. He spins these into stream-of-consciousness sentences uttered, at 63, in tones of childlike wonderment, even when the context is decidedly adult.

He’s unbelievably dedicated to his work, his art. He’s not kicking back a bit and that really surprised me. Some artists, after three or four decades, are mellow. He’s focused

Courbet is a favourite. The 2014 Gagosian Hong Kong show, mostly, featured Koons’ “Hulk Elvis” sculptures: each comic character looked exactly like a gossamer-light inflatable, complete with air nozzle, but, being made of bronze, weighed 800kg. When I asked him if that was the joke, Koons replied, “It’s not a joke. It’s really a philosophical discourse – art deals with the internal and external, that’s really the dialogue.”

There were also some oil paintings, one of which, Couple (Dots) Landscape from 2009, depicted two people externally copulating beneath what appeared to be a quick sketch of a misshapen doughnut. “Those silver lines refer to Origin of the World,” Koons had explained.

This time round, the artist will be in Hong Kong with the David Zwirner gallery, for whom he is featured artist at this week’s Art Basel Hong Kong. One of the works on display will be Bluebird Planter, a piece from his “Banality” series (2010-2016). His explanation of the concept is standard Koons speak: “I’ll take a small ceramic object and scan it and capture everything about its surface and then proceed to make a new work in stainless steel with a completely reflective surface. It’s a piece that can connect you to the idea of a planter and how accessible something like that is. But it can also tie you back through human history to, you know, Ovid and, you know, the idea of the mythic and to biology … the ongoing continuation of different realms of the eternal through biology, life continuing to leapfrog and procreate, and the eternal through ideas.

“I think the piece captures that.”

The viewer, that’s what it’s about, that’s really what art is. The object is something other than art – it’s a transponder, it stimulates, it excites but it doesn’t have potential. The viewer has potential

“These works are very metaphysical,” he murmurs, quietly awed. “And they’re metaphysical in that they reflect you. You know, a gazing ball works like a GPS system, it tells you where you are in the universe at this time. It affirms you. Because when you look at it, your senses become excited … the excitement from the ball and the reflection … and you feel the connection to human history of really being able to stand on the shoulders of all our forebears.”

“Like a selfie?” I murmur (reflectively). Koons, who appears to be incapable of irony, hesitates. “In a normal selfie, there’s a lack of profundity, in a way,” he says. He politely mentions the selfies taken by his youngest daughter, one of his eight children (six by his wife, Justine Wheeler): “The comfortability with the self, I think, is very, very impressive.”

Random questions in interviews usually fuel new trains of thought but Koons, who says he is interviewed about once a fortnight, has long perfected a single-track mindset and soon he is back to musing on his balls. (“Everything is metaphor,” as he states, later. “Everything.”)

“The viewer, that’s what it’s about, that’s really what art is,” he continues. “The object is something other than art – it’s a transponder, it stimulates, it excites but it doesn’t have potential. The viewer has potential.”

Doesn’t that lessen the creator? “The creator is participating in transcendence,” Koons says. “I learned early on that there were certain strengths I had as an individual. Once you learn how to accept yourself, you’re able to really open yourself up to the external world.” When was that? “I would say early 20s. My first art-history class, I realised – wow! I was so excited – wow! I want to become – and here’s this perfect vehicle. Once you learn how to experience transcendence, you automatically want to share that with the community.”

The trouble, of course, is that not all communities are into transcendence sharing. “You know,” Koons says, “anxiety and fear really limit us as human beings from really reaching a total consciousness. People become very, very judgmental. They segregate. They alienate. They don’t open themselves up, and art is an area when you can get an understanding pretty quickly of an individual for the rest of their life.”

When economist Don Thompson wanted a title with sufficient bite for his recent book, which is subtitled Bubbles, Turmoil and Avarice in the Contemporary Art Market, he chose a 21st-century icon: The Orange Balloon Dog. In 1994, Koons had made five stainless-steel balloon dogs in red, magenta, blue, yellow and orange as part of his “Celebration” series. On November 12, 2013, at Christie’s New York auction house, Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994) became the most expensive piece of art by a living artist sold at auction when it went for US$58.4 million.

At the time of the sale, Koons said that his Balloon Dogs were like Trojan horses. He seems to have been referring to the contrast between shiny external and dark internal. Perhaps he also meant the gulf between that childhood-related work, which began as an artistic celebration for the return of his son Ludwig – born in 1992 and carried off to Rome by Staller two years later – and the ensuing bitter years he spent fighting to get custody. But you do not have to be a classical scholar to understand the link between geeks bearing gifts and the current judgment of Paris.

People say, ‘Oh, it’s industrial business.’ [...] they believe that art still has to be involved in a kind of arts and crafts. I believe that by remaining myself, being able to conceive of an idea and to create a certain type of plastic art, that I’m able to enhance the power of that experience

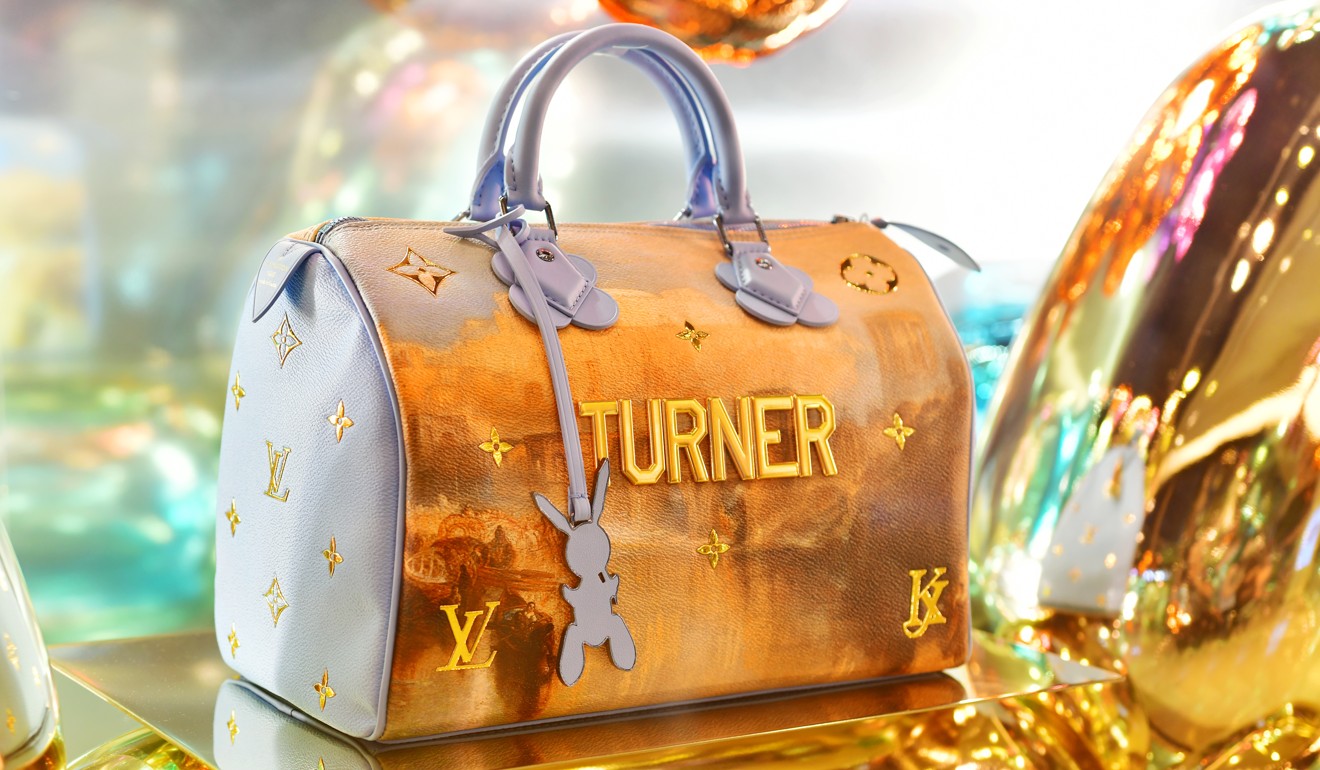

The actual US$4.3 million cost of making Bouquet of Tulips in Germany and installing it has been funded separately but, since the plan was announced in November 2016, dissent has – in typically Koons fashion – grown in size. In January, French newspaper Libération published a letter from various prominent figures, including a former minister for culture, that listed objections to the plan on symbolic, democratic, architectural, artistic and financial grounds. It described Koons as “the emblem of industrial art” and his studio, and those who sold his work, as “multinationals of hyperluxe”. This was surely a particular dig at Louis Vuitton, for whom Koons has designed a range of handbags.

At first, when I bring this up, Koons’ voice drops even lower. “I can’t speak on Paris right now,” he says. Still, doesn’t it go to the heart of his creative theory? If power is in the eyes of the viewer, then hasn’t he handed power to those outside himself?

“A lot of times we really take for granted that people open themselves to experience,” he replies. “And again, art is just one area and so you can imagine that if someone really doesn’t open themselves up to a painting or a sculpture or contemplating a possibility of some conceptual work … they’re probably not opening themselves up in other areas in their lives.”

A week after this interview, another French letter appeared, this time in Le Monde. Various prominent figures, including a former minister for culture, listed occasions when the city had initially objected to projects (the Pompidou Centre, I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre) it had later grown to cherish. Koons was described as “a great lover of France”.

Whatever happens, Snapchat may have provided a solution, of sorts. Last autumn, it announced that it was collaborating with Koons on an “augmented reality” project, which basically means anyone can place Koons’ sculptures in specific locations and take a selfie. One of Snapchat’s examples showed a mammoth Rabbit (1986) next to the Eiffel Tower. As Evan Spiegel, Snapchat’s founder, smoothly remarked, it is a way “to remove friction from the creative process”.

A large car arrives. On our way out, one of Koons’ staff gently adjusts my coat collar; maybe perfection has become habitual. The pair of us climb into the back and are driven a few blocks round the corner to the David Zwirner gallery on West 20th Street. En route, Koons talks about his studio. He has been there for 18 years but the area is being developed and so he will leave in January. Of his new place, he says, “I like to think of it as a studio for the rest of my life, something that really functions for the needs of creating my work.”

It happened that the following day I interviewed artist Sarah Morris (whose show “Odysseus Factor” opened at Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art on March 24). “I worked for Jeff before he had a studio,” she said, in her own large workspace. “It was in his apartment, when he was working on ‘Made in Heaven’. This was before he had a hundred people working for him, it was really just me. Full on? Yes! But I learned a lot and we also had a lot of fun.”

Clearly visible on the shelf just behind her right shoulder was a postcard of Courbet’s The Origin of the World.

Afterwards, talking to David Zwirner in his office, the late-afternoon wintry city beyond the windows will have a brilliant Koons sheen to it. Zwirner will say, “He’s unbelievably dedicated to his work, his art. He’s not kicking back a bit and that really surprised me. Some artists, after three or four decades, are mellow. He’s focused.”

He’ll add, “Some artists stand behind their work, some artists stand in front of it – that’s not so good. He stands next to it. He supports it, that’s part of his calling. It’s one of the reasons he said he’d come to Hong Kong. He’ll make himself available in front of his work.”

But I already know that. Standing in the gallery with Koons, you can see how the bluebird is still part of him. He points out the imperfections carried over from the original, the perfect recreation of all its flaws. When I ask him what he’s thinking as he walks around, looking at it, he says, “I’m accepting my own history.”

But when I ask what kind of flowers have to be planted in its back, he gives a little shrug and says, “Any.” So it is possible to let it go? “It’s about control,” he smiles. “And giving up control.”

Art Basel Hong Kong is open to the public on March 29 (1pm-9pm), March 30 (1pm-8pm) and March 31 (11am-6pm).