A Mr Big of wildlife trafficking: could elusive Laos casino operator be behind rackets that run to drugs, child prostitution?

Mystery surrounds business empire with office in Hong Kong accused by US authorities of running an international criminal organisation in a small corner of Laos

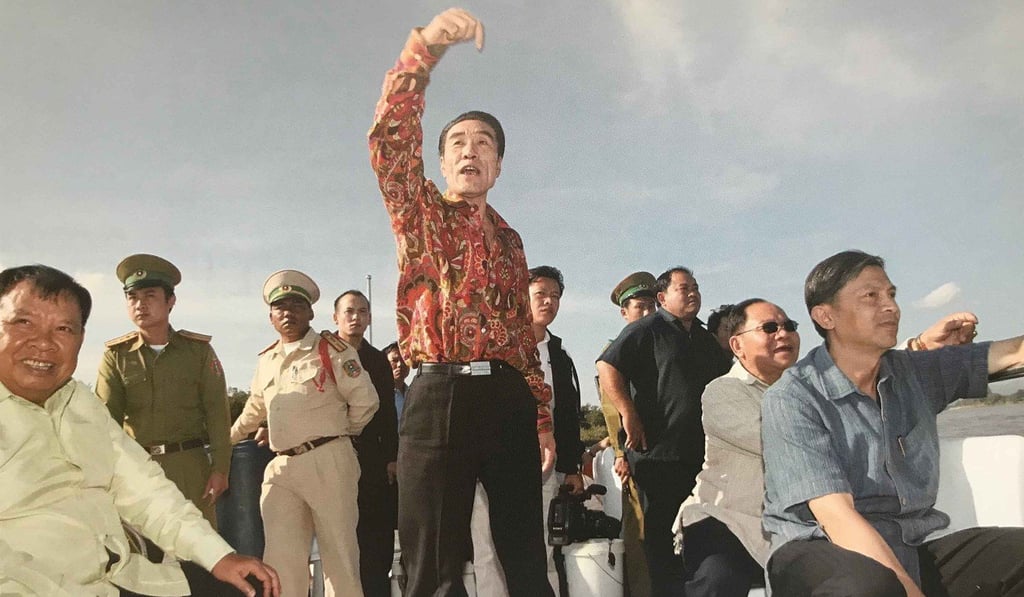

Powerful, well connected and fabulously wealthy, 58-year-old Su Guiqin is queen of the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, a small enclave in the far northwest of Laosthat, just over a decade ago, was a poor fishing village on the Mekong River. With her husband, Zhao Wei, she now runs the Kings Romans empire, a Hong Kong-registered business that took out a 99-year lease on a 3,000-hectare chunk of Bokeo province in a deal with the Laos government in 2007 and transformed it into a lavish gambling resort.

Hundreds of millions of US dollars of investment poured in as jungle, rice paddies and peasant homes were cleared to make way for a casino dripping in gold paint and filled with classical-style statues, a five-star hotel, karaoke bars and restaurants, all built along replica traditional Chinese streets.

Farming families that were moved off the land on which they had lived for generations were promised the casino complex would be followed by a hi-tech zone and an agro-industrial area that would bring wealth and opportunities to the poverty-racked district. They are still waiting.

Meanwhile, the area has been transformed into a de facto colony in which the only currencies accepted are Chinese yuan and Thai baht. This is a place for Chinese tourists to gamble and party. Few employees are Lao nationals.

The “economic zone” is nothing of the sort, according to a searing new indictment from the United States government. In January, the US Treasury Department announced sanctions against what it calls Zhao’s transnational criminal organisation, naming two registered Hong Kong companies under the Kings Romans Group as its corporate fronts and identifying Zhao and Su as the organisation’s leaders.