American author on her Burma rebel leader mother and feeling disenchanted with Aung San Suu Kyi

Actress-turned-novelist Charmaine Craig’s mother – who went from beauty queen to resistance fighter – was the inspiration behind a 15-year project to ‘better understand Myanmar’s present through the past’

“

It’s strange to be something that no one else has heard of, and you don’t see anyone else from that community around you. You might as well be saying, ‘I am from Mars.’ When I was a little child, that’s what it felt like: ‘I am ‘The Other.’”

When bestselling novelist Charmaine Craig tells me this, speaking from her home in Los Angeles, in the United States, my initial response is to raise an eyebrow. Craig’s outsider credentials are not immediately obvious. An actor by training, she possesses movie-star good looks and, as her literary career attests, a powerful intellect to match. The author of two acclaimed novels, The Good Men (2002) and Miss Burma (2017), she supplements her writing by teaching literature and creative writing at the University of California, Riverside. Away from work, Craig is married to fellow writer Andrew Winer and is mother to two daughters.

However, this blissful summary barely touches the complexity of Harvard-educated Craig’s family history, the roots of which reach across the Pacific to the minority Karen people of Myanmar’s Irrawaddy Delta.

Craig is the daughter of Louisa Benson Craig, a woman of Karen and Jewish ancestry, two-time winner of the Miss Burma beauty pageant (in 1956 and 1958), once the country’s most famous film star, the (falsely) rumoured mistress of military dictator General Ne Win and a Karen resistance hero.

Louisa married Brigadier General Lin Htin, commander of the Karen National Liberation Army, in 1964. After his assassination the following year, she attempted to unify the many and diverse pro-democratic groups in Burma (now Myanmar) while under constant threat to her life from the ruling military government. The risks eventually grew so pressing that Louisa fled her homeland in 1967, settling eventually in the US.

“As epic as her life was, as colourful as it was, that doesn’t make a book,” Craig says. “Those events can be told in about five pages. What’s essential for any story is why and how? How did a young woman from a double minority become the most famous girl in a country that is extraordinarily racist? And why did she, who professed she did not want to be in that position, permit that to happen, and assist in that happening?”

As a child, I strongly identified as Karen because it meant ‘outsider’ to me. Now I am shy about it because I don’t like to pretend I’m an insider when I’m not

Craig spent two years interviewing her mother in search of answers.

“She was so generous with her time,” Craig says. “She was so good about telling me everything she could, but it was as if she was describing fate pulling her from point to point. There mostly didn’t seem to be any ability to convey what her own motivations were.”

Craig suggests two explanations for this matter-of-fact narrative.

“Part of her coping strategy as a person is not doing a lot of self-analysis, not really looking back,” she says. “It was my job as a novelist to do that work for her, not that I would presume to know what she was doing.”

For example, Craig gleaned few insights into her mother’s fame, which began in 1956, when she was crowned Miss Burma at the age of 15. “Louisa always said it was a burden and very undesirable,” Craig says, adding that her mother saw herself as a tomboy who preferred sports and reading to glamour.

Then why did she enter Miss Burma a second time, winning again in 1958?

In Miss Burma, this crisis is the turning point in Louisa’s life – the period during which she evolves from empty celebrity into zealous hero of the Karen people. Again, Louisa saw this transformation as destined rather than willed. Her marriage to Lin Htin was expedient: “[Louisa said,] ‘He was strong when I needed him to be strong. Everyone else was falling apart around me. He didn’t care – about the rumours, about what people said about him. He was a way out.’”

A similar mood of passive acceptance surrounded her succession of Lin Htin’s leadership.

“When she heard he might have been assassinated, Louisa decided to give her life to the Karen completely,” Craig says. “She was prepared to die. I found some of her letters to her father from this time and she really described it in terms of fate. She saw that her whole life had led to this point – to be a champion for the Karen.”

During this period, which takes place after Miss Burma ends, Louisa advocated for the Karen and strove to forge alliances with Burma’s other minority peoples. “She spent the next two decades of her life very actively involved in pro-democratic human rights for Burma,” Craig says.

Louisa maintained good relations with Bo Mya, the novelist believes, despite his execution of Lin Htin’s men.

“She did not leave because of a ‘power struggle’ with Bo Mya,” Craig says, arguing against what many – including Wikipedia – have come to believe. “She left because she married my dad. She remained friends with Bo Mya. He stayed in our house in Los Angeles.”

Even in exile, Louisa campaigned tirelessly for the Karen: in 1996, she succeeded in ratifying a pan-ethnic peace agreement. While she returned to areas held by the Karen military, she never again went back to Rangoon (now Yangon) or Burma’s delta region. “She had a price on her head. She was an enemy of the state until she died.”

Louisa’s American life is not told in Miss Burma. That began some years earlier, in 1959, at Tufts University, in Medford, Massachusetts, where she met Glenn Craig – the novelist’s father.

After Lin Htin’s death in 1965, Glenn wrote her several letters and the couple reunited in Bangkok, Thailand, in 1967.

“They were married a week later,” says Craig.

Growing up in California has sometimes resulted in an identity crisis for the writer. On her last visit to Myanmar, in 2012, a Karen man asked whether she considered herself American or Karen.

“I replied, ‘I guess I am 50 per cent American and 50 per cent Karen.’ He said, ‘Wrong answer. You should be 100 per cent Karen.’’’ She laughs. “As a child, I strongly identified as Karen because it meant ‘outsider’ to me. Now I am shy about it because I don’t like to pretend I’m an insider when I’m not.”

In many respects, the delicate balance between belonging and exclusion is central to Karen identity.

Searing images of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh camps

How did Louisa adapt to her American life? Craig ponders a different question: where did her mother feel most at home?

“The Karens didn’t belong. Louisa’s own mother and father didn’t belong,” she says. (Mother Naw Chit Khin was Karen; father Saw Benson was Indian-Jewish.) “Louisa spent her last years in Burma as an enemy of the state, fleeing from place to place so she wouldn’t be killed. The truth is she never felt she belonged so much as she did to those soldiers in the end.”

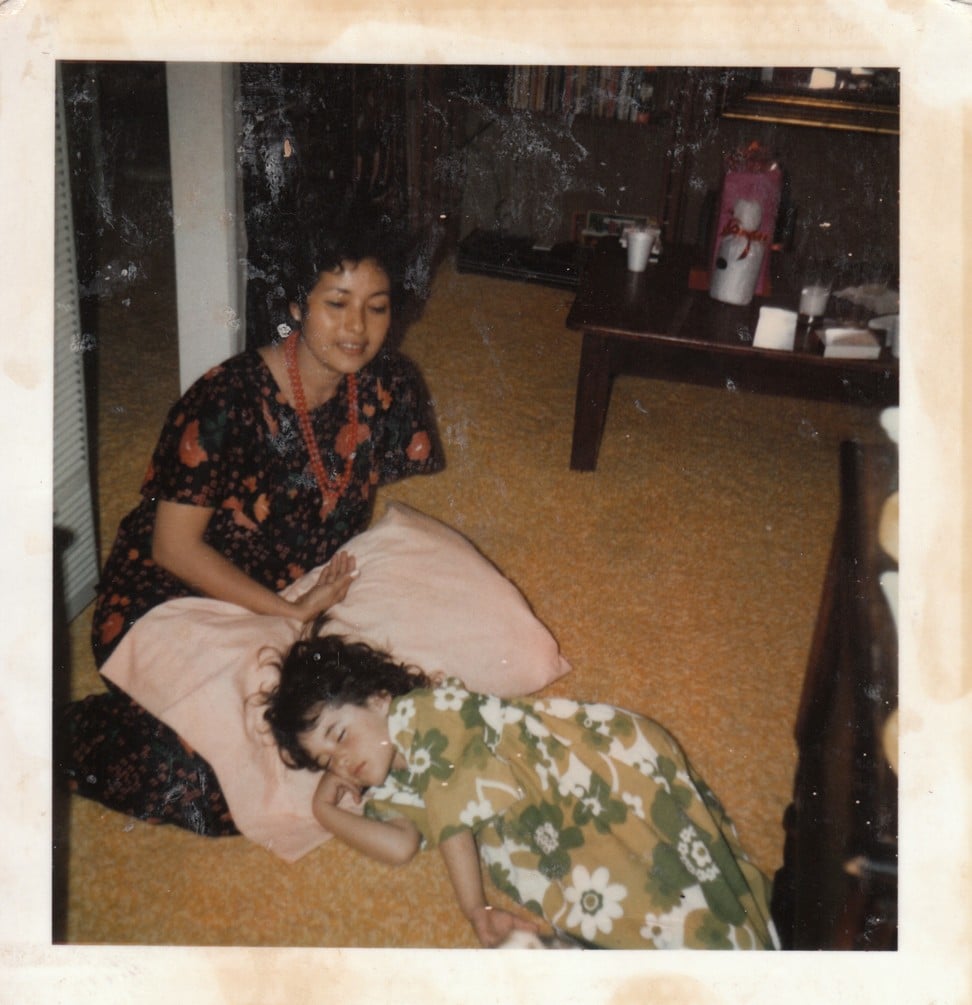

This devotion made Louisa a Karen hero, but the impact on her daughter was less straightforward.

“For the first 16 or 17 years of my life, my feeling is [my mother] didn’t like being in America at all,” the novelist explains. “She appreciated things about it, but there was a refrain I heard when I was little: ‘I want to go back to Burma.’ I didn’t feel she fully belonged to me. I felt she was this close to leaving me and going to where she really belonged.”

The turning point, ironically, was Louisa’s return to the Myanmar border region, when she was forced to reassess her identity in much the same way her daughter would in 2012.

“That is when I think she realised how American she had become. In the following decades, I didn’t hear, ‘I want to go back.’” Craig pauses. “Of course, the damage had been done.”

Craig’s own first-hand experience of Myanmar has been confined to the same border areas, which are sometimes called “Karen Land”.

“It is so familiar. It explained myself to myself,” says Craig, who speaks of Karen culture with something approaching reverence. “They are slow to trust because of all the ways they have been burned, but once they do, you are one of them. It doesn’t matter where you come from. They are by nature welcoming and peaceful, with a bawdy sense of humour. The egalitarianism of their social structures means that one can be relaxed because one doesn’t constantly have to assert one’s own individual advantages or greatness.”

How life is changing for Thailand’s Karen tribe

This idyllic portrait appears to contrast with the values espoused by Craig’s home city of Los Angeles. The home of Hollywood did, however, allow her to follow her mother into acting: Craig’s modest on-camera résumé includes roles in the television series Northern Exposure (1990-95) and film White Fang 2 (1994).

“Quality roles were really not available to me because of the way I look and my ethnicity,” she says. “The only parts I ever got were Native American, and the only auditions I would be sent out on would be for exotic types or aliens from outer space. Perhaps times have changed – I have been out of it for so long – but I suspect that is still to some extent true.”

Writing came to Craig’s rescue in 1996, when she won a place on a prestigious graduate creative writing programme at the University of California, Irvine.

“I didn’t expect to get in,” she says. “They only take three men and three women a year.”

At the time, Craig was shooting a TV pilot – Barefoot in Paradise – starring a youthful Ricky Martin. (“It was like Beverly Hills, 90210 on a yacht.”) When the writing programme’s director called, she was told there was a catch. “‘Your acceptance into the programme is contingent on your severing your ties with Hollywood. It will be too tempting to continue to act if you are offered parts,’” she remembers the conversation. “I said, ‘You don’t have to worry about that.’ I remember the elation I felt for the rest of the shoot.”

In yet another twist, Hollywood was responsible for bringing Craig together with one of Louisa’s old friends: Myanmar’s state counsellor and winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize, Aung San Suu Kyi. “They knew one another from their childhoods and their lives in Burma,” Craig says.

The writer met Suu Kyi at a “Hollywood function” in late 2012, partly thrown to honour Louisa, who had passed away two years earlier. “This is before [Suu Kyi] was scrutinised by the world,” Craig says. “Before the world lost its faith in her.”

The year 2012, in fact, was a high point in the world’s love affair with Suu Kyi, with Vanity Fair magazine gushing that her “heroism stems not from physical or military prowess but from moral power: her tireless work for democracy and human rights in the face of brutal opposition”.

Craig felt differently. “I felt disenchanted, if you will,” she says. “In the US, at least, it seemed the media had an eagerness to uphold a particular narrative about Burma opening up and democratising, and about Aung San Suu Kyi in particular, that was not rooted in reality.”

[Aung San Suu Kyi’s] silence now about the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya is not unexpected for me, nor would it have been for my mother

At the Hollywood event, actor Ed Norton was sitting beside Suu Kyi, the guest of honour, and moved aside to let Craig speak with her. “I did come prepared, having consulted Karen leaders to try to communicate their perspective and the broader perspectives of the ethnic minority community,” she remembers.

Her efforts were in vain, however, although not quite in the way she might have imagined. “I tried to bring up the political and she kept introducing the personal,” Craig recalls. “‘Tell me about your mother’s brother. Tell me about your father.’ It was like two people speaking different languages. It became clear that she was so tired of speaking about politics. She was desperate for a human connection.

“She began to tear up and cry when I began talking about the various people who had died. We spoke about her husband. He had been one of my professors at Harvard. It wasn’t an act.”

Undercutting Craig’s sympathy, however, lies political scepticism. “She has been an outspoken advocate of democracy, but her version of democracy is a bit different from a liberal version of democracy – for the protection of the minorities or, you might say, for the protection of all,” Craig says. “In [Suu Kyi’s] case, it would seem to be for the protection of the majority, whether or not she privately has different views.”

Before meeting Suu Kyi in 2012, Craig had tried for many years to place op-ed articles exposing the deep schisms in Myanmar between the dominant Burmans – once represented by Suu Kyi’s father, Aung San – and other ethnic groups, including the Karen and Rohingya. One early draft of Miss Burma included a lengthy critique of Suu Kyi.

“I ended up cutting that part after I showed it to a few people,” Craig says. “They didn’t understand why I was so critical.”

What did Louisa think of her old friend in later years?

“My mother was able to hold a full range of views,” Craig says. “On the one hand, she knew Aung San Suu Kyi to be an exceptionally intelligent woman who in her own way did bravely bring her intelligence and voice to the pro-democrat movement. But even during the two decades of [Suu Kyi’s] house arrest, that same voice shut down with respect to the plight of the persecuted minority people. Her silence now about the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya is not unexpected for me, nor would it have been for my mother.”

Craig says the Rohingya crisis has distracted the international community from the breakdown of the peace process between ethnic minority groups and the Myanmar army.

“That has all but fallen apart,” she says, “because the military has felt emboldened to say to the ethnic minority groups, ‘You will do it our way or no way.’”

There have been renewed attacks on the Karen in violation of existing peace agreements, Craig claims. “Burma is on the precipice of falling back into warfare,” she adds. “It’s an example of how the world’s black-and-white thinking about Burma has strengthened the military and weakened the position of the pro-democratic groups who are seeking a more pluralistic society.”

And Craig has mixed feelings about having completed Miss Burma, although there is relief at finishing a project that took 15 years, and which she describes in terms of duty.

“Who else was going to write this story? I don’t mean to sound hubristic,” she says. “Given what I inherited, I did feel I had to. Part of my duty was to teach people as simply and elegantly as possible how we might better understand Burma’s present through the past, and our own involvement in that past.”

Finishing may have been a release, but it was also a cause for sadness.

“It marked the end of this sustained conversation with and appreciation of my mother,” Craig explains. “I knew I would never have that again. I will think of her, often. I will seek answers from her, in my own way. I will miss her, but I will [never again] spend every single day absorbed in the question of her life and her spirit.”

Given Craig’s sometimes fraught relationship with her mother, I ask whether writing Miss Burma helped in any way – with understanding and possibly forgiveness.

“I haven’t thought about it in that way,” she says. “But I think it absolutely must have. I think I had to get that first version out of my system in order to put myself in the margins of the story. I remember when she died, I was still struggling to forgive some things, but I don’t feel that any more. So you must be right.”

While there are no plans to continue Louisa’s story – and perhaps her own – one recent revelation might at least give pause for thought. Miss Burma has been published in Myanmar with considerable success, quickly running into a second printing.

“It has done very well,” Craig confirms. “But people want a sequel. We will see.”