Climate change: how long do we really have to save the planet from catastrophe?

- Scientists cannot seem to agree on the numbers, but there is a consensus on one thing: the human race is in imminent danger

- Mainstream media also cause confusion, neglecting to connect increasingly chaotic weather patterns with human behaviour

12 years to save the planet. Warming of 3 degrees Celsius, or perhaps 5 degrees if we don’t take drastic action now. A sea-level rise of 0.3 metres by 2100 – or is it three metres?

Just about every article you read on climate change is full of numbers, starting with 1.5 degrees, which, we are told, represents the maximum temperature rise we can allow and still avoid the worst effects of global warming.

Except it isn’t – and that is just the beginning of the confusion. No two numbers from climate-change studies ever seem to agree. Even climate scientists are often baffled by the figures other researchers come up with.

Climate-change deniers seize on the uncertainty as evidence that the underlying science is wrong. It is not. It is just complex, as real-world science is. The biggest uncertainty by far is us and what we will do over the next century. And the uncertainty cuts both ways: we could be underestimating how fast the world will warm and what the effects will be.

So what numbers can and can’t we be certain of?

How much has the planet warmed already?

As part of the Paris Agreement of December 2015, nearly every country agreed to work towards limiting the rise in global average temperature to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

To work out what that means, we must first understand where we are now. The uncertainty starts here. We might have as much as 0.6 degrees to go before we cross the threshold – or less than 0.3 degrees.

How can we not know how much the world has warmed?

The best way to measure global warming would be to look at the whole by examining land, sea and atmosphere. But our measurements focus on the thin layer we live in: mean global surface temperature usually refers to the warmth of the air two metres above the surface.

We monitor changes in this temperature from thousands of weather stations on land, and from ships and buoys at sea. Each reading is checked to see whether the temperature is lower or higher than the long-term average in that location at that time of year. The readings are then combined to show how the average global surface temperature is changing relative to the long-term average, or baseline.

There are problems with this approach. For instance, while weather stations on land monitor the air two metres above ground, marine observations are usually of sea surface temperature. And because it is not possible to have fixed weather stations in an ocean full of shifting ice, there are few measurements from the Arctic.

The HadCRUT temperature record, maintained by Britain’s Met Office, simply leaves the Arctic out. Nasa’s GISTEMP record estimates Arctic temperatures based on surrounding stations. Because the Arctic is warming rapidly, the United States space agency’s figures suggest there has been nearly 0.1 degrees more warming across the planet than the Met Office’s do.

Further confusion surrounds the baseline question. Reliable global temperature records go back no further than 1850, but the industrial age began a century earlier. Computer models suggest that by 1850 the world was already up to 0.2 degrees warmer than it had been.

Despite this, the average temperature between 1850 and 1900 has come to be regarded as the semi-official “pre-industrial level”, because that is the earliest period for which we have direct measurements.

“I don’t think there’s much appetite in the community for changing this,” says Ed Hawkins, a professor of climate science at Britain’s University of Reading who has been involved in many of the relevant studies.

Use the Met Office record and take 1850 to 1900 as a baseline, and there has been about 0.9 degrees of warming to date. Go with Nasa and the earlier, pre-industrial baseline, and that number jumps to 1.2 degrees.

With the world on course to warm by far more than 1.5 degrees, that difference is minor. But if we are serious about limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, it really matters. “With 1.5, a difference of 0.1 is a huge amount,” says Hawkins.

What is the safe limit for warming?

Not 1.5 degrees. That was picked not because it is the right number, but for convenience. A 1990 report by the non-profit Stockholm Environment Institute concluded that limiting global warming to 1 degree would be safer than a 2-degree cap. But in 1996, with 1 degree out of reach, 2 degrees was adopted as a target by the European Union’s Council of ministers, leading to its 2010 adoption by the United Nations.

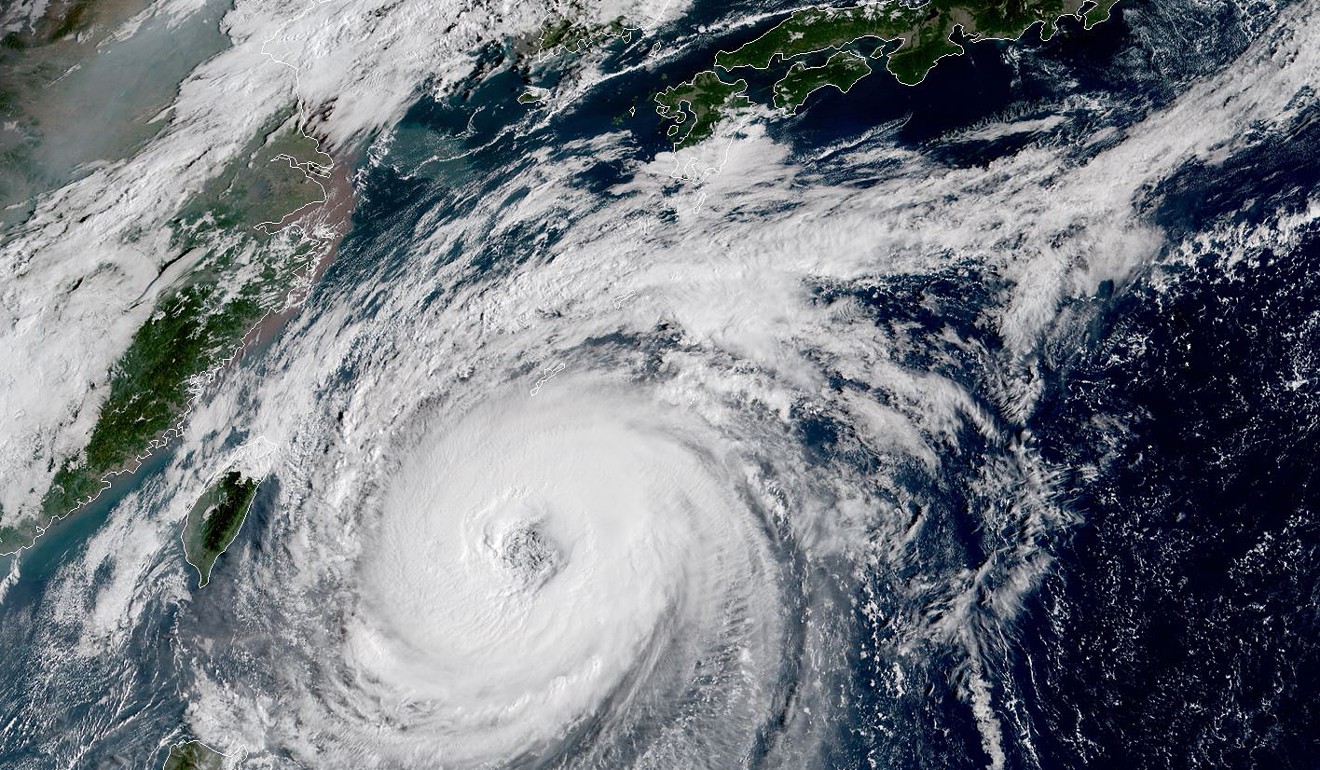

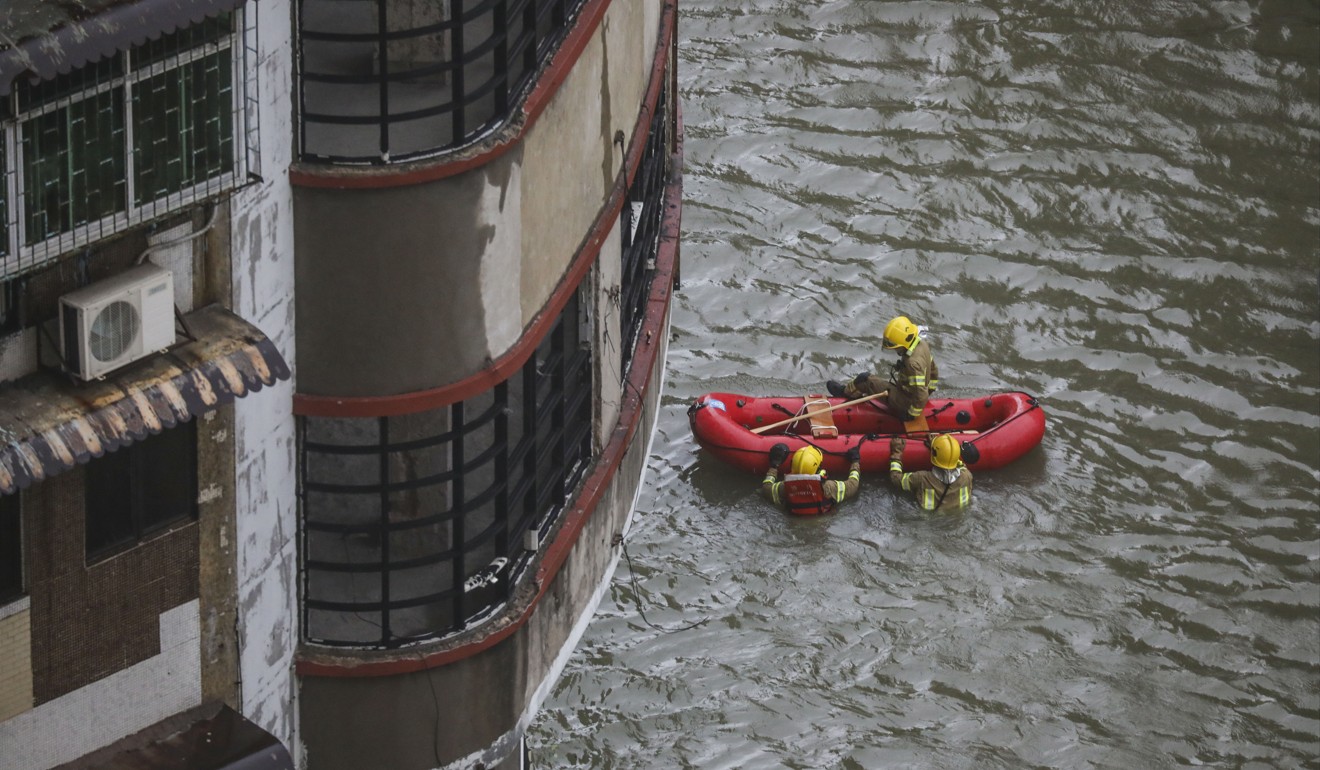

There is growing evidence that warming is fuelling record-breaking extremes. The devastating storms, incredible heatwaves and rampaging wildfires we are now seeing show that “safe” is a matter of degree. As the world gets hotter, the downsides of global warming, from coral bleaching to severe flooding, will grow more pronounced.

Then there are potential tipping points such as the shutdown of the Atlantic current that warms northern Europe. But as we don’t know at what temperatures these will kick in, this doesn’t help with the establishment of a “safe” limit.

And the dangers associated with any level of warming depend in part on us. If we stop building on coasts doomed to disappear under the waves and start adapting our homes to cope with greater weather extremes, we will save lives.

When are we set to pass the 1.5-degree limit?

On current trends, the first year in which we will exceed 1.5 degrees above the 1850 to 1900 average will probably fall in the 2020s. But because climate is weather-averaged over many years, it would be premature to regard this as the passing of the limit. The threshold is likely to be crossed during an El Niño, a period in which warm waters spread across the Pacific and temporarily boost the global surface temperature.

A reasonable definition is that we will cross the limit when the average, long-term temperature rise exceeds 1.5 degrees. Following current trajectories, this is likely to happen around 2040 – sufficiently close that many scientists and politicians have adopted a somewhat different definition of reaching the 1.5-degree limit. Almost all of the scenarios considered in the IPCC report involve getting the temperature rise back below the 1.5-degree threshold by 2100 after exceeding it by the middle of this century.

That’s a bit like giving someone a credit card with no spending limit. If you rack up a lot of debt, the only way to repay it – to get the temperature back down after an overshoot – is to reduce the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by removing it in vast quantities. At present, there are many ways of capturing carbon on a small scale, but no technology that works on the stupendous scale required to reverse decades of fossil-fuel burning.

Even if we can get the temperature back down, the effects will be more serious than if we did not pass 1.5 degrees because there will be faster warming over the next few decades. That could trigger tipping points that cannot be easily reversed, such as the die-off of the Amazon rainforest. And once you start relying on science-fiction scenarios, you can justify a much wider range of numbers.

How much warming does CO2 cause?

This is perhaps the toughest question in climate science. CO2 directly warms the planet by trapping more of the sun’s heat. That is the easy part. But it also triggers all kinds of feedbacks that affect global temperature. Some kick in almost instantly: for instance, more warming means more water vapour, which is a powerful greenhouse gas. Cloud behaviour also changes immediately.

Other feedbacks take thousands of years. Warming will be amplified as vast, reflective ice sheets melt and are replaced by dark land and water more absorbent of sunlight, for example. Adding to the confusion are numerous other pollutants that we are pumping into the atmosphere, some of which have a cooling effect.

This not only makes it harder to determine how much warming CO2 causes, but also to work out what we need to do to limit warming, which depends on how levels of these pollutants change, too.

A common measure of climate sensitivity is how much warming would occur in the decades and centuries after a doubling of CO2 levels. Studies converge on the most likely value being 3 degrees, but with plausible projections ranging from under 2 degrees to more than 5 degrees. If emissions continue to rise, CO2 will be at double pre-industrial levels in less than 50 years.

While we are increasingly confident that the low end of the plausible range can be ruled out, a long tail of high values cannot. Last year, some climate scientists warned that we may be greatly under-estimating the risks, and that if the planet did warm by at least 2 degrees, it might be impossible to stop it warming several degrees further.

How much more CO2 can we emit?

Even if we remain unsure of the climate’s exact sensitivity to CO2 and other greenhouse gases, it is clear that what matters is how much is in the atmosphere. Less is definitely more.

An IPCC report in 2013 estimated that, for a 66 per cent chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees, the carbon budget from 2018 was 118 gigatonnes of CO2. The seemingly equivalent figure in the latest report is 420 gigatonnes.

The higher budget is partly a result of some genuine good news. Earlier calculations had relied on estimated emissions over the past century, and used computer models that slightly overestimated temperature rise. Better models and more accurate figures have meant in an increase in the amount of CO2 we can get away with emitting.

But the latest IPCC report acknowledges that budgets can vary widely for the reasons we have already covered. For instance, using different temperature records can bring the budget down to 258 gigatonnes or raise it as high as 570.

Even these numbers conceal huge uncertainty. The budgets could be 650 gigatonnes lower or higher, depending on climate sensitivity and the historical baseline, meaning we might have already exceeded even the biggest budget. In addition, the report says, if wetlands were to release more methane and melting permafrost more carbon than assumed, the budgets would be 100 gigatonnes lower.

Most carbon budgets are what Glen Peters, a research director at the Centre for International Climate Research, in Norway, calls “exceedance budgets”. These set out how much CO2 we can emit up to the point where the temperature rise passes 1.5 degrees. Using the analogy of a bungee jump, this would be equivalent to the length of rope with which you would hit the ground.

Ideally, you would jump with a rope that is a little shorter: an “avoidance budget” with which you never actually hit 1.5 degrees. It is even more likely that we have already busted such budgets.

The budgets in the IPCC’s latest report are different again. They are based on when emissions will hit zero in scenarios that assume we overshoot 1.5 degrees, but then cool the planet back down by extracting carbon from the air. “Once you allow negative emissions, the carbon budget is an ill-defined concept,” says Peters.

Confused? You are not alone. “Everyone is confused,” he says.

How high will the seas rise?

During the warm period between ice ages about 120,000 years ago, temperatures were about 1 degree warmer than from 1850 to 1900, and the sea level was six to nine metres higher. In other words, even if we limited warming to 1.5 degrees, much of the ice in Greenland and west Antarctica could be lost, which would be enough to raise sea levels by five metres or more.

Without a change of course, we are actually heading for a world that is 3 or 4 degrees warmer, which could lead to seas rising more than 20 metres. The big unknown is how long this will take. Because the planet’s temperature is rising much faster now than it did during any recent warm periods, the past is not a good guide to our future.

The prevailing view is that it will take many centuries or millennia. IPCC projections are for sea levels to rise by between 0.3 and 0.8 metres by 2100 in a world that is 1.5 degrees warmer, and by 0.5 metres to one metre by the end of the century if emissions continue increasing unchecked. If it remains warm, there will be bigger sea-level rises to come in the 22nd century and beyond.

Some scientists regard these projections as conservative. Antarctica is losing ice much faster than expected, and a 2016 study based on a computer model of its ice sheets suggests the seas could rise by up to three metres by 2100.

How long do we have to turn things around?

“Scientists say we have 12 years to save the world.” That is the message many seem to have taken from the latest IPCC report – but that is not quite what the report says.

It is true that at the current rate of emissions we will exceed the report’s “most likely” remaining carbon budget in about 12 years. But as we have seen, carbon budgets are set at the midpoints of wide ranges, and the 1.5-degree target itself is an arbitrary one.

We have also been here before. Climate-change deniers gleefully point out that we have already been told several times that there are just X years to save the planet. So focusing on arbitrary deadlines is perhaps not the best way to sum up the science.

“I personally don’t like the 12 years,” says Piers Forster, a professor of physical climate change at Britain’s University of Leeds, and one of the authors of the IPCC report. “We, in fact, have to act immediately in a larger way than ever before.”

Amid the morass of confusing and conflicting numbers, two things are crystal clear. First, we have to reduce net global emissions to zero, and the faster we do that the better off we will be. Second, how bad the impact is will depend in part on how much we do to prepare for it.

It’s time to get serious about adapting to life on a warmer planet.

New Scientist

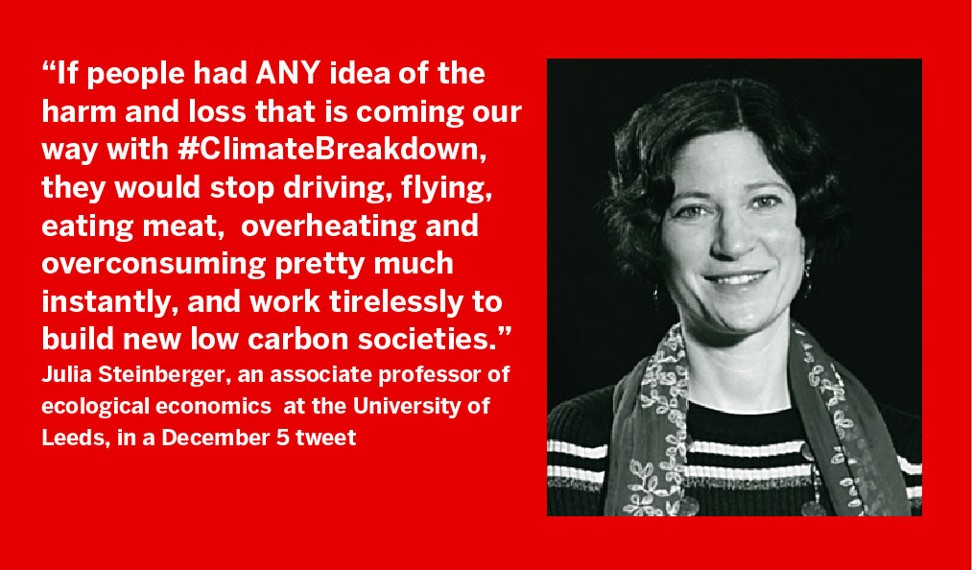

The stand-alone quotes used with this article were first assembled by website Media Lens, for use in the alert, “Veneration of power leading to climate catastrophe”.