Video game addiction: why the mental disorder, now recognised by the WHO, is on the rise

- Summer holidays identified as addiction danger spot as youngsters spend unstructured time online

- The Cabin in Chiang Mai offers a rehab programme for young male addicts but, at US$15,000 a month, it’s out of reach for many

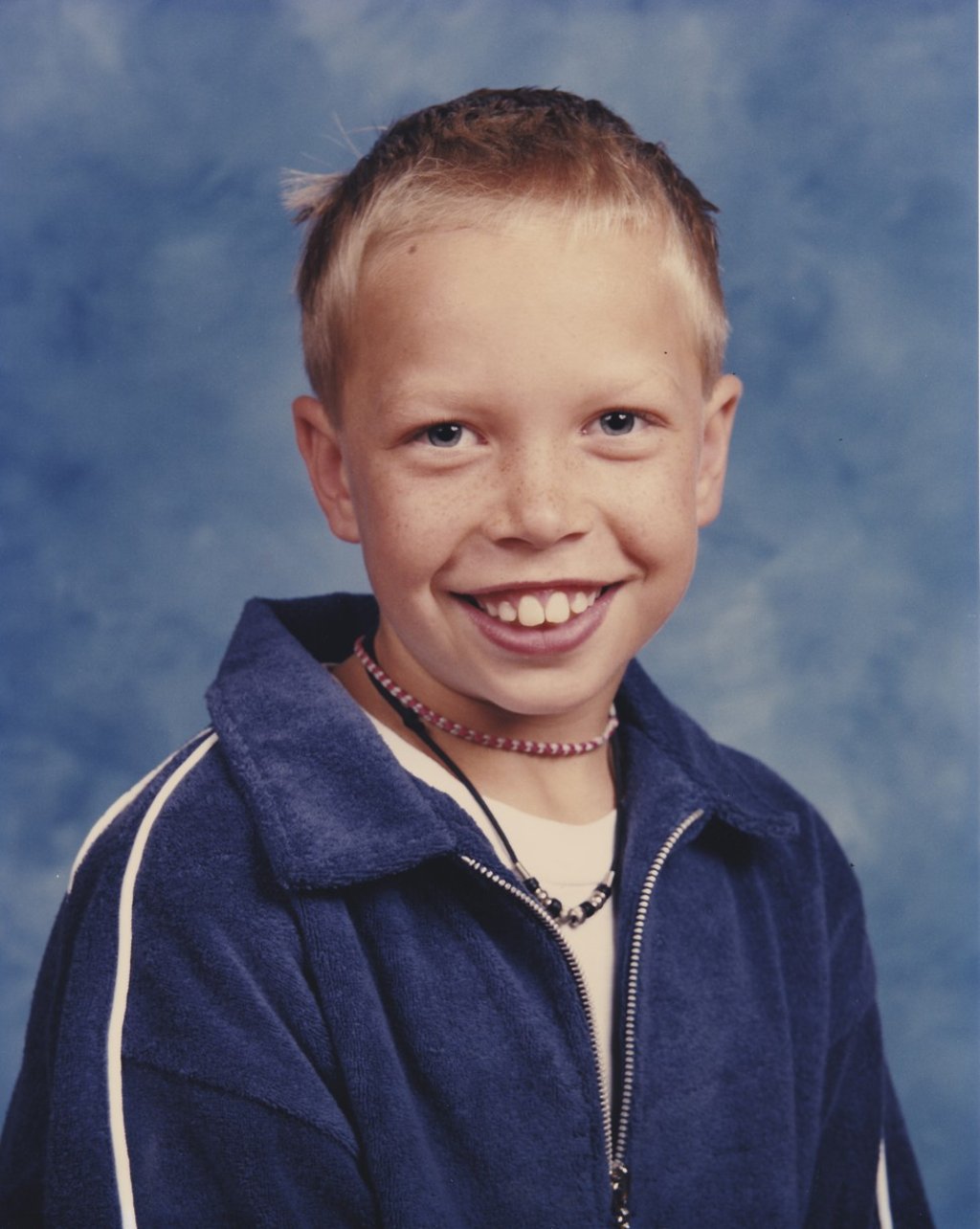

For many addicts, there comes a point when they hit rock bottom and realise they need help. For Cam Adair that time came when he was 19.

“I went from having jobs and not keeping them, to pretending to have jobs and refusing to work, to having suicidal thoughts, to planning my suicide,” says Adair, a former athlete who had dropped out of school and was living with his parents in Calgary, Canada. His addiction? Online games; he spent 16 hours a day vying for virtual galactic supremacy while in reality he was hunched over a computer in his bedroom.

“I wrote a suicide note. To my dad I wrote, ‘I’m sorry, I wish you didn’t hate video games so much because they mean a lot to me,’” Adair says when we speak in a simply furnished group-session room overlooking lush lawns at The Cabin, in Chiang Mai, Thailand, which is home to The Edge programme for young men with addiction and behavioural issues.

Adair was writing his suicide note, he says, when a friend called and invited him to join a group going to see the teen comedy Superbad (2007). They smoked marijuana before visiting the cinema and, as Adair belly-laughed through the movie, he was struck by the realisation that he wasn’t safe with himself. When he got home that night he told his father he was struggling and asked for help finding a counsellor.

Today, Adair, 30, operates – as its founder – Game Quitters, a support community for video-game addiction.

Adair began playing video games when he was 11, encouraged by a cousin who was four years his senior.