International House: how an anonymous Chinese student sparked a century of cultural exchanges

- A chance encounter outside a Columbia University library in New York planted seed for global movement celebrating multiculturalism

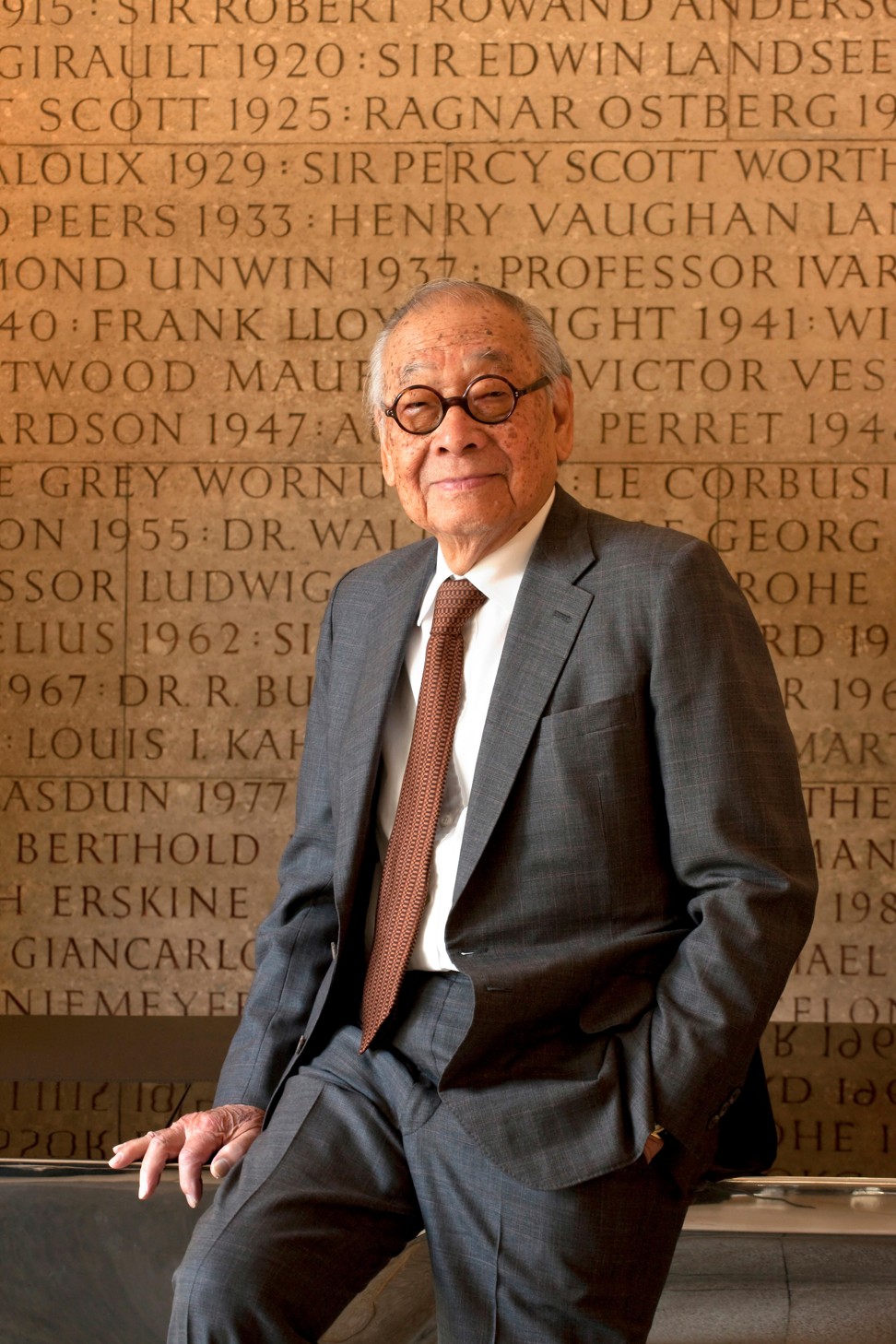

- Alumni of the worldwide academic accommodation initiative include architect I.M. Pei and Nigerian author Chinua Achebe

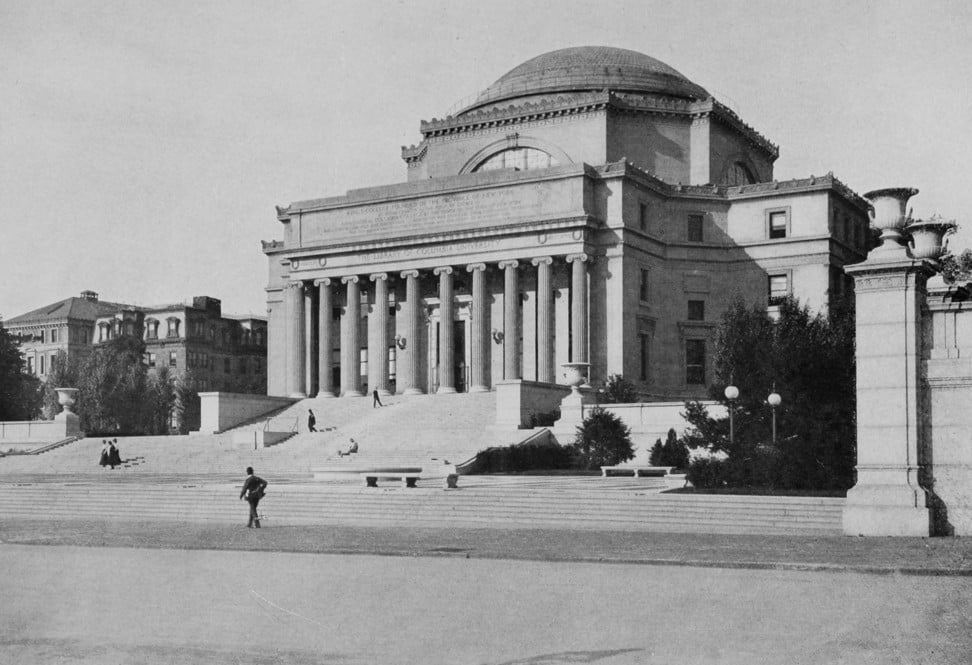

That morning in the autumn of 1909 was frosty, an early hint of the bitter New York winter to come. The young Chinese student who’d just left Columbia University’s Low Memorial Library and was walking down its impressive front steps must have felt the chill. He was a long way from home. When a passing American cheerfully greeted him (“Good morning!”), he stopped. The American, being of a curious mind, turned back to find out why.

“I’ve been in New York three weeks,” the student said. “And you are the first person who’s spoken to me.”

The passer-by was a 26-year-old graduate engineer from New York state called Harry Edmonds. A few years earlier, he’d been offered a job at what was then called Canton Christian College and is now Lingnan University, in Guangzhou. He hadn’t taken the position and maybe a memory of that opportunity prompted the friendly impulse. Or maybe he was just someone who recognised loneliness in a crowd.

Edmonds apologised to the student. He explained that New Yorkers tended to speak only to people they knew. The pair exchanged names and parted. Passing behind the library Edmonds realised, as he put it in an oral history, that “something extraordinary” had happened. He felt it was a tragedy that his city had ignored “a fellow who had come from the other side of the world, China, to study in America”. He went back to find him but he’d vanished – forever, as it turns out. Edmonds didn’t record his name.

The encounter on the Low steps lasted a few minutes. When Edmonds told his wife, Florence, she wanted further action. He did some research. There were several hundred foreign students studying in New York and the Edmondses began inviting small groups of them over for Sunday tea. Eating cake in front of the fireplace, he said, “their national identity sort of dissolved, they were just friendly, jovial, talkative students”.

Out of those teas grew Sunday suppers in Columbia’s chaplaincy at Earl Hall. In 1912, Edmonds and Bayard Dodge, son of philanthropist Cleveland H. Dodge (the family money came from mining), founded the Intercollegiate Cosmopolitan Club, which was affiliated with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA).

After the first world war, when many overseas students left their ravaged countries for New York, Edmonds realised accommodation was a problem, especially for non-whites. He decided to build a residence for students.

Another capitalist philanthropist, John D. Rockefeller Jnr, was approached for money. Rockefeller believed that foreign students – potential leaders in their own lands – offered an excellent opportunity to improve America’s standing abroad. (“As these young men and women from the nations of the world are received with sympathy, interest and cordiality by the United States, they will naturally cherish a friendly feeling for our country.”) He encouraged Edmonds to think bigger and provided the means to do so.

In September 1924, 15 years after two young men briefly spoke to one another on the Low Memorial Library steps, the first International House opened, in Manhattan, at 500 Riverside Drive. It had 13 floors and 525 rooms for both foreign and local graduate students: Americans were an essential part of the mix. Over the entrance stood a motto: That Brotherhood May Prevail.

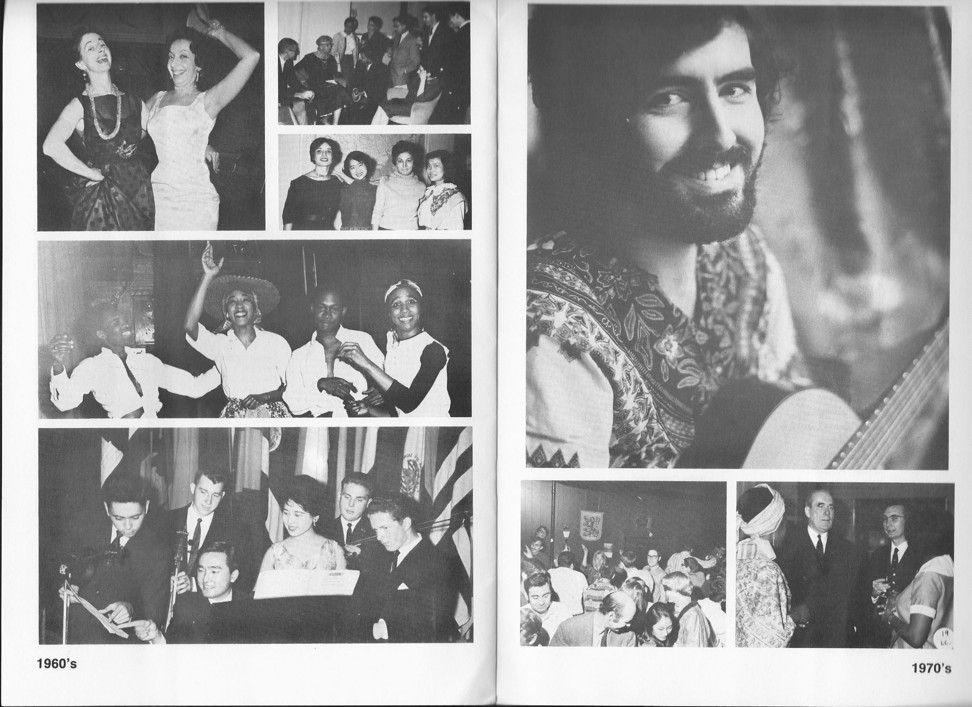

Luckily, sisterhood was also allowed to prevail and Christianity was no longer the prime belief. When the Gideons came calling with Bibles for every room, the committee politely said no. The doors of I-House New York were open to students “from any land without discrimination because of religion, nationality, race, colour or sex”. Under its roof would live individuals as culturally distinct yet united as (future Man Booker Prize winning author) Kiran Desai, (future Pritzker Prize winning architect) I.M. Pei and (future Man Booker International Prize winner) Chinua Achebe.

In 1930, a second International House was established, at Berkeley. California had been selected because it was the point of entry from Asia; the address, on Piedmont Avenue, was chosen by Edmonds because the neighbouring fraternities and sororities excluded foreigners and black Americans. Two years later, I-House Chicago was founded.

Now 17 International Houses, on three continents, are affiliated to International Houses Worldwide. Each is a separate, non-profit-making entity. The biggest (1,800 residents) is in Bucharest, Romania. None is in Asia. But in March, for the first time, I-House New York moved its annual gala beyond the US, to Shanghai.

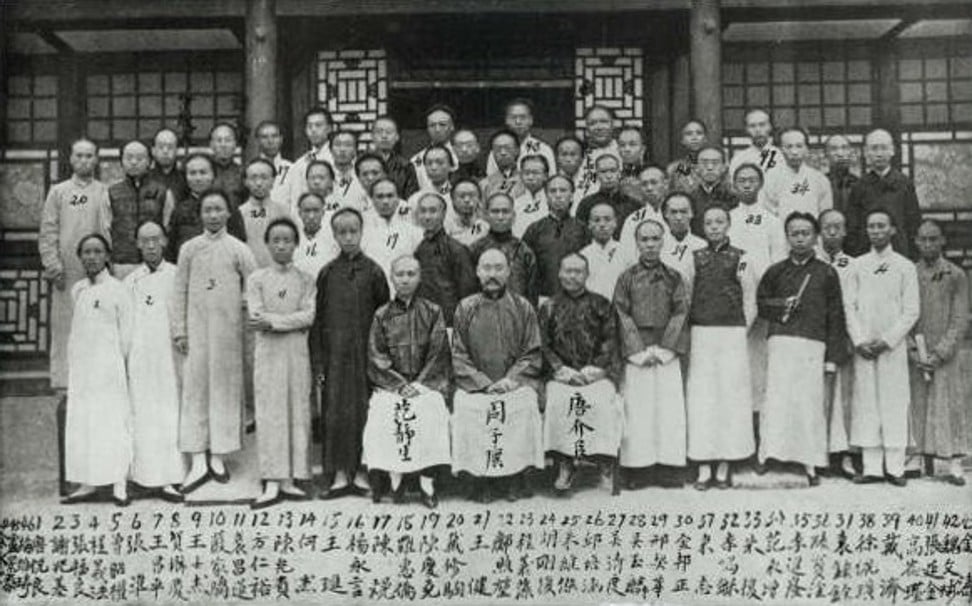

It’s likely that the Chinese student – that anonymous catalyst who inspired what’s now called the “I-House Experience” with its core values of respect, empathy and moral courage – was attending Columbia on one of the first Boxer Indemnity scholarships.

When it became apparent that the US had been given more money than originally agreed (it was paid in gold, not silver), president Theodore Roosevelt decided the excess should be used to fund scholarships for Chinese students in America. That, he felt, would impress American values on young Chinese minds.

On December 3, 1907, in his State of the Union address, Roosevelt said, “This nation should help in every practicable way in the education of the Chinese people so that the vast and populous Empire of China may gradually adapt itself to modern conditions.”

In 1908, a bill was passed in the US Congress. Students began to arrive the following autumn.

“I like the fact that in the Wikipedia photo of the first group he’s in there somewhere, the man who started it all,” says Alice Lewthwaite, Harry Edmonds’ British great-granddaughter. She’s referring to the group portrait of the initial 47 students who, in 1909, set sail for the US from Shanghai. She’s hoping to narrow down the search even further. “I’ve got a copy of the 1909/10 registration at Columbia and there were 15 Chinese students at the time, although not all of them may have started in the fall.”

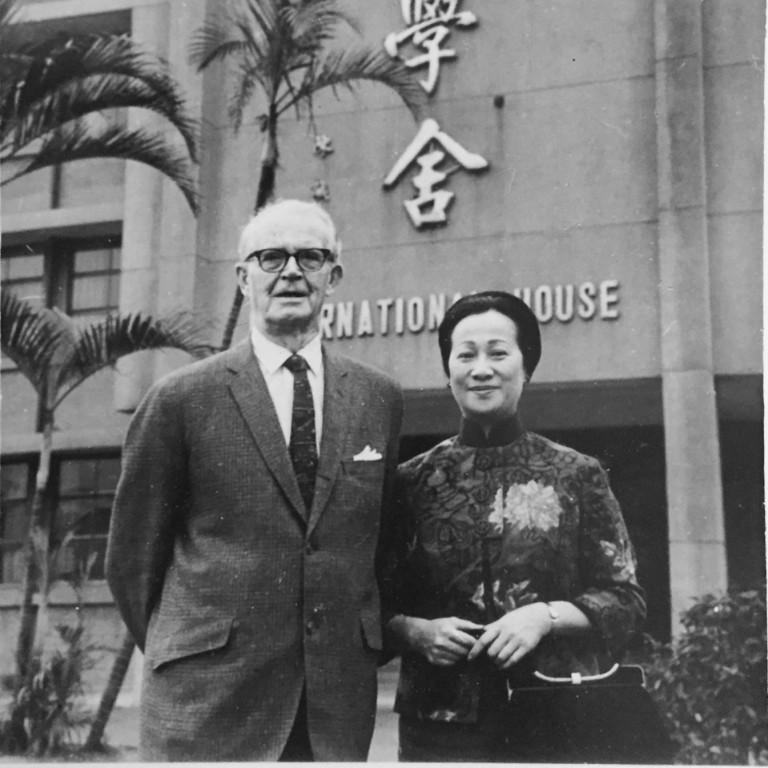

It’s late January and Lewthwaite is in Hong Kong. In January 1966, her great-grandfather came here as part of a world tour. The South China Morning Post dutifully noted both his arrival and a dinner hosted by International House alumnus William Choy, whose father, Choy Chong, founded the Sun department stores in Hong Kong and Shanghai. Edmonds was then 83. In 104 days he travelled, by himself, from New York to Berkeley, Honolulu, Tokyo, Taipei, Manila, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Delhi, Karachi, Tehran, Beirut, Istanbul, Athens, Rome, Paris, Berlin, Helsinki, Oslo, Copenhagen and London.

Lewthwaite, who shares a March 11 birthday with her great-grandfather – and whose easy-going friendliness could be genetic – is marking her 50th by replicating that itinerary. When Edmonds was torn between going to Canton Christian College or staying in New York, a prescient Christian adviser had told him that, in China, he’d just be “one grain of sand on the seashore, one drop in the bucket”. If he stayed in America, however, he could influence many grains of sand. To honour her relative, Lewthwaite has called her journey the 100,000 Grains of Sand tour. (As International House New York alone has 65,000 alumni, 100,000 is actually an underestimation, but it makes the point nicely.)

Despite living in the US during her early childhood, while her great-grandfather was alive, Lewthwaite never met him. Harmony can be easier to promote on a global scale than within a family and there’d been a breach after Florence died, in 1933. Harry’s daughter, Markie – Alice’s grandmother – barely spoke to her father again.

It wasn’t until 2009, therefore, when International House New York was celebrating the 100th anniversary of the meeting on the steps, that Alice and her two children visited an I-House for the first time and met Sandy, Harry’s American granddaughter. And it was only in 2017, when she read the transcript of her great-grandfather’s oral history that she decided to recreate his trip.

“I’ve done consulting roles in organisations so it seemed like an amazing thing to have taken an idea and created it into an institution,” she says. “I thought I’d expand his trip, that I’d go to Africa, mainland China. But the problem is there are 80 countries represented in the Houses. Do you go to Nepal? Do you go to Chile? So I decided to stick to his original route.”

Today in Hong Kong is day 20. Facebook has made social arrangements easier than in 1966 – although Edmonds still managed to meet about 1,000 alumni – and she’s organised an early-evening gathering at Commissary in Pacific Place. By now, she’s met her first Sakura Sweethearts, in Hawaii; these are couples who’ve met at I-House New York, the name a tribute to the canoodling corners of nearby Sakura Park.

She’s also met her first I-House baby, in Manila – Maria Angelina Fatima, born in 2014 when her mother, Doris Ramirez, a student on Columbia’s Human Rights Advocacy Programme, went into labour prematurely. By contrast, Edmonds, on his Philippines stopover, met President Ferdinand Marcos, who, in January 1966, had been in office less than a month and wasn’t, yet, troubling human rights activists.

Numbers have been modest in Taipei and Tokyo but, in Hong Kong, about 20 cheerful and voluble alumni from I-Houses in Berkeley, Sydney and New York turn up.

“My most noisy and wonderfully effervescent crowd,” Lewthwaite says, halfway through the evening. What strikes an onlooker, not surprisingly, is the global fluidity. Or, as Jeanne Zhao-Clot – a typical example, being born in Zhejiang, educated in Beijing, Paris and Berkeley, married to a Frenchman and currently helping cosmetic companies move into China – puts it, “I am truly international!” Her I-House Berkeley roommate was a German woman who gave her pizza recipes; one of her contemporaries was a Norwegian prince.

Socially and culturally for me it was a huge awakening. The rooms were Hong-Kong sized, deliberately designed so you must socialise

“Socially and culturally for me it was a huge awakening,” says Joanna C. Lee, who was born and brought up in Hong Kong, studied at London’s Royal College of Music, stayed at International House New York for three years in the 1980s, when she was doing her doctorate in musicology at Columbia, and is on its World Council of Alumni. “The rooms were Hong-Kong sized, deliberately designed so you must socialise. If you wanted a social life, you didn’t have to leave the House – we had ballroom dancing classes, discussion groups, important speakers like [former US Supreme Court judge] Sandra Day O’Connor.”

Each I-House has its own traditions but most have retained the Sunday suppers and candle-lighting ceremonies begun by Edmonds more than a century ago. Before her tour started, Lewthwaite decided she should use it, literally, to pass the light from one place to the next. On a table in Commissary, she sets up a photo of Harry and Florence and three candles: a big one she’s carrying to every country, one she’s carried as a present from Manila to Hong Kong, one she’ll carry as a present from Hong Kong to Bangkok.

The group gathers round respectfully. “At the first event in International House, everyone asks, ‘Where are you from?’” remarks Vivien Chiu Shih-yu (born in Taiwan, brought up in South Africa, educated in Cape Town and at Columbia, now studying law at the University of Hong Kong). “And then everyone mingles. That’s the fun thing.”

When Edmonds returned to New York, he wrote a letter on April 20, 1966, addressed to his Friends around the World. “Will Brotherhood ever prevail?” he asked. “Yes, I believe man is rapidly approaching that point. Brotherhood must prevail, or else!”

When Lewthwaite returns to England after her 73-day trip (which, unlike her great-grandfather’s journey, didn’t include Karachi or Tehran) the world’s brotherhood isn’t entirely evident. As she writes on her blog, “Nothing has really changed and we still haven’t sorted Brexit!”

As it happens, the I-House Shanghai gala is on March 29, the day Britain was supposed to leave the European Union. References to this, and President Xi Jinping’s European trip, can be heard in snatches of conversation at the pre-dinner drinks party. Among the 120 guests, many of them Chinese alumni from around Asia, is the descendant of another International House moving spirit – Peter O’Neill, whose great-grandfather was John D. Rockefeller Jnr.

“I’m the fourth-generation to serve on the board,” he says. “And I lived in International House New York in 1991-92.” During that time, O’Neill, who as his name suggests, looks Irish (“The red hand of Ulster!” he cries as a salute to his other ancestors), told no one of the family connection. He still has an unassuming demeanour; he’s happy to engage in amiable conversation with passers-by, even a journalist. Of the interplay between local and global residents in the I-Houses, he remarks, “Americans probably have the most to learn, right?”

The last time O’Neill was in Shanghai was in 1981 (“with the family”). “I’m so impressed with Chinese energy and intellect, what they’ve accomplished.” In 1981, Pudong was an unpromising huddle of low, dark warehouses and rice-fields. “Now, there are millions of people and it’s bigger than New York.”

Indeed. In his pre-banquet speech, Calvin Sims, president of International House New York, refers to its origin story. In this Shanghai telling, the lonely student on the Low Memorial Library steps says good morning first and Harry Edmonds responds. Who knows? Perhaps it was that way round. What’s clear is that the unknown student would have to fight his way into the House today. Chinese residents make up 90 of 700 places, the biggest overseas group. Numbers are regulated to keep the mix sufficiently international. “We seek out the best and brightest,” says Sims. “And we take only one of five who apply.”

At times the gala, rather like the world, seems uncertain on which aspect of China to focus. There’s a quartet of young Chinese women in red playing Strauss waltzes and operatic excerpts from The Peony Pavilion and a guqin player: the fine-fingered flutterings of an ancient civilisation. (Meanwhile Joanna C. Lee isn’t at the Shanghai gala because she’s the PR and media consultant for the Cleveland Orchestra, in China for its first tour since 1998.)

Edmonds had another great-granddaughter. Her name is Mira Edmonds and since 2015, she’s been living in Shanghai. Her husband, Doug, works for Apple. He stayed at I-House Berkeley when he was doing his PhD in economic sociology but they’d been dating for a while before this relevant information emerged.

When we meet for coffee in Xintiandi, she has her newly adopted dog, Bobby, with her so we sit outside, on Madang Road. “I came to China with two kids and a cat and I’m leaving with three kids, three cats and a dog,” she says. The family is moving to Michigan, in the US, where she’ll teach at the University of Michigan’s law school.

Unlike her second cousin Alice, Mira met Harry when she was a baby. After he died, in 1979, his memory was kept alive by her mother, Sandy. She thinks there may have been an unconscious international influence: she lived in Ecuador for a while and after attending Harvard University, she worked at the Social Science Research Council in New York, on the Cuba programme.

Nevertheless, it’s living in China that’s shown her what it’s like to be the other, the person on the outside looking in. She knows she’s in a privileged minority but she’s also illiterate, stared at and she doesn’t understand much of what’s going on around her.

“That gave me a lot of empathy with migrants,” she says.

Some time ago, she joined a running group, which had some Chinese members, and went away for the weekend. It was the International House effect in microcosm. “When I came back, I said to Doug, ‘I think I have a Chinese friend.’ It took me 2½ years to say that.”

Her youngest, aged three – Harry’s great-great-granddaughter – is now bilingual, in Chinese and English. And, nowadays, there’s a House of Roosevelt on the Bund. It’s a dining establishment and club (“patronised by royalty, diplomats, social elites and the highly distinguished”, says the website). The chairman of the company investing in it is Theodore Roosevelt’s great-grandson, Tweed.

Maybe the original student’s great-grandchildren are in this city. His ghost hovers. While we’re talking on the busy lunchtime street, smiling young people keep coming up to sell us cleaning solvents, shoe-polish spray. We shake our heads, they move on; and pretty soon, when you glance back, they’ve been swallowed up by the masses.