Finding the yeti: Daniel Taylor on his decades-long search and what discovery means for the future of humankind

The American scholar and conservationist recalls how a picture of a footprint in a newspaper sparked a lifelong ambition to solve a centuries-old mystery

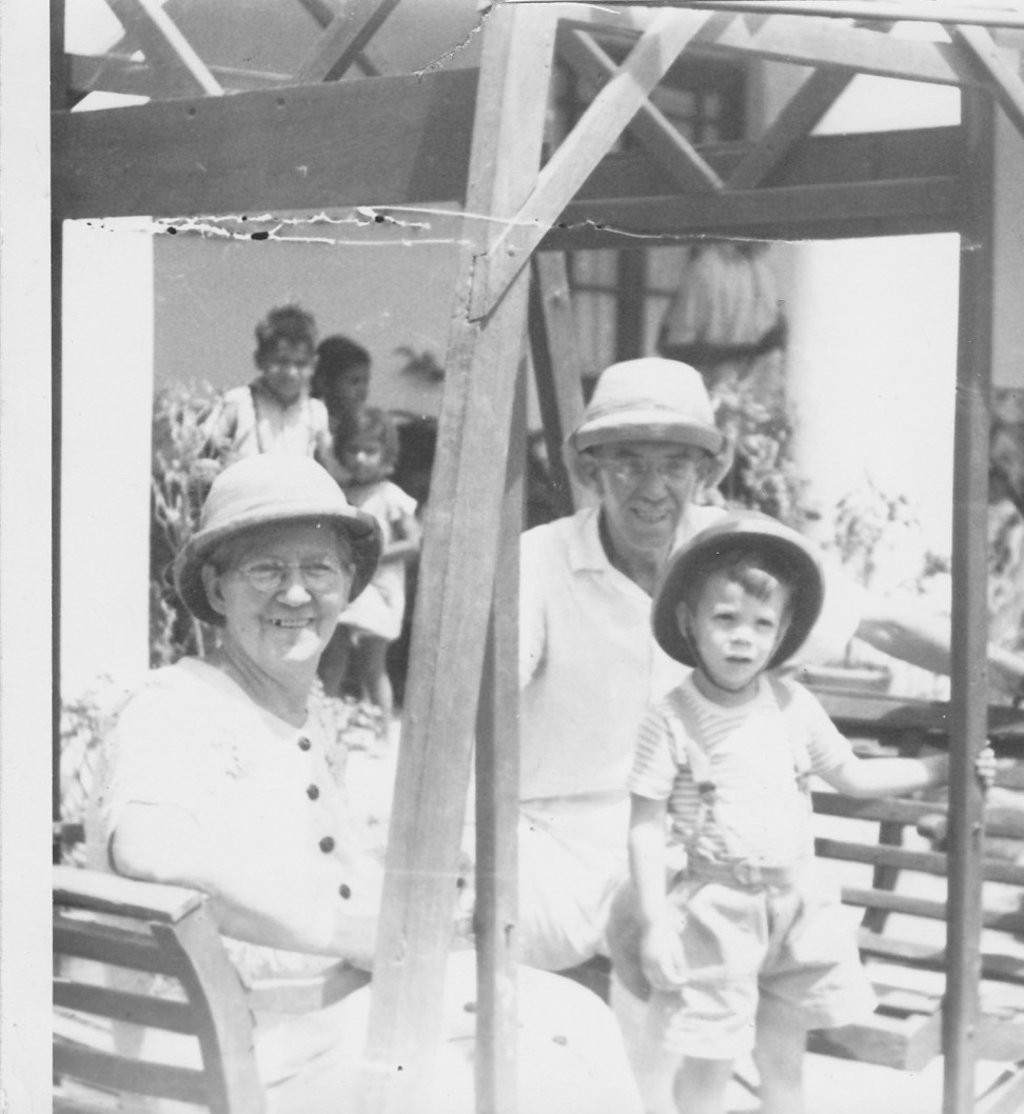

Rumble in the jungle My grandparents were cowboys in Kansas. They paid their way through medical school and after they graduated went to India to work as medical missionaries, just before the first world war. My father and his siblings were born in India. When my father was four months old, he was almost taken from a tent by a she-wolf in the jungle in north India. His nanny slammed her pith helmet against the wolf, and she dropped him.

My father, Carl Taylor, went to the United States for medical school. He met and married my mother, Mary, and I was born in 1945, in Pennsylvania. My parents travelled to India to do medical work in early 1947, just before independence, and I went with them.

My father was among the first Americans to go into Nepal in 1949 (Nepal has been isolated for most of its history and only started opening up to foreign visitors in the mid-1940s). It was a good childhood. My playmates were the village children – I spoke to them in Hindi. Today, I also speak Urdu, Nepali and some Punjabi.

Wrong footed When I was 11, I noticed a picture on the cover of The Statesman newspaper of a footprint in the snow. That was the beginning of my fascination with the yeti. The story quoted a curator at the British Museum saying the print wasn’t humanoid as everyone thought, he said it was the print of the langur monkey. I thought that was ridiculous; I played in the jungle and knew the langur well.

My father was doing community-based medicine in Nepal and we moved around a lot with him. I always asked people about the yeti. It was evident to me that we weren’t talking about a myth – it was a real animal because there were real footprints. My father went back to the US to go to Harvard University to teach the community-based approach to medicine that he had developed in India. We were going back and forth between India and the US. By the time I was 18, I’d spent 12 years in India and six in the US.