BBC journalist Emily Maitlis on her history with Hong Kong and fixing the gender pay gap

- The first female lead presenter of BBC current affairs show Newsnight has come a long way from her days as ‘a terrible journalist’

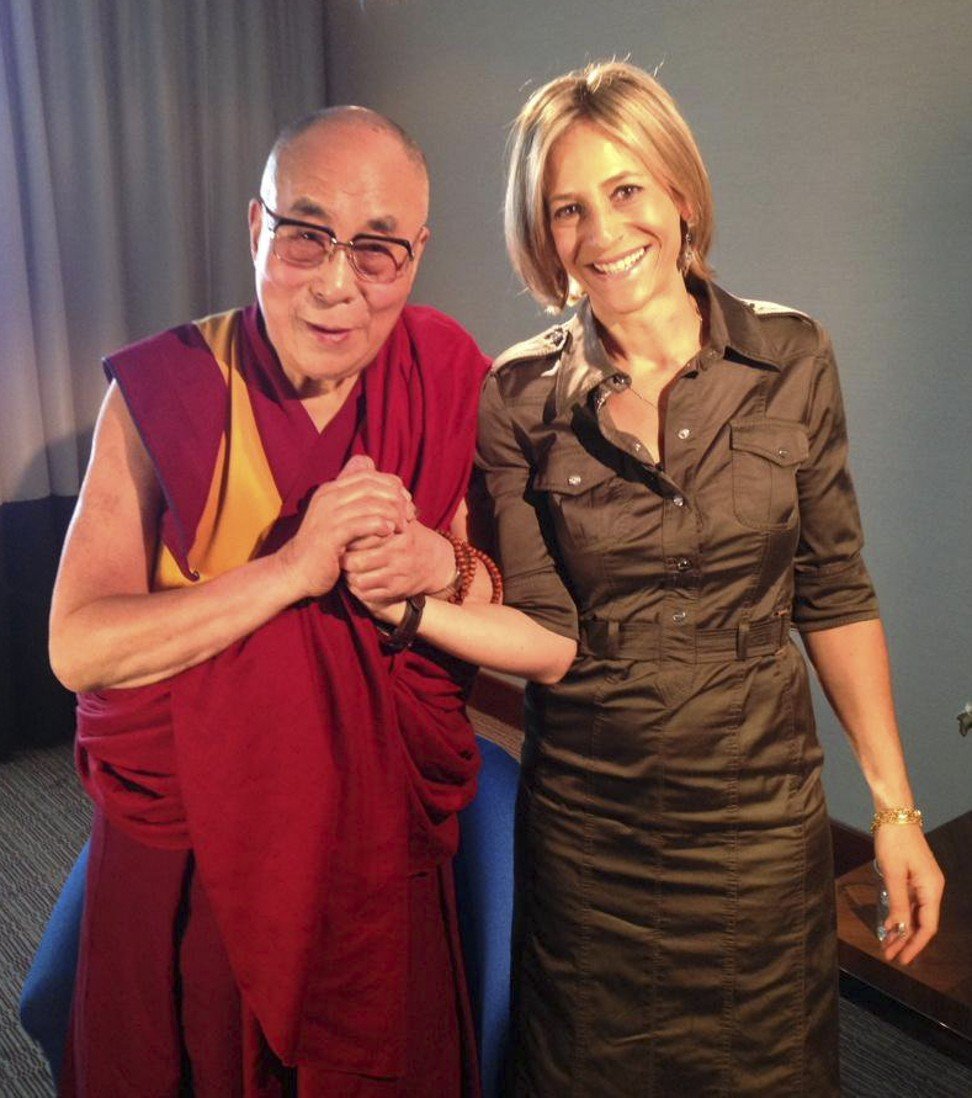

- Now a household name in Britain, she has interviewed everyone from the Dalai Lama to Donald Trump

It is 11 minutes past three, the morning after our interview, and Emily Maitlis is sending me a Twitter message, having woken up with an urgent need to clarify something we spoke about yesterday afternoon.

This is not unusual. After hosting an edition of Newsnight, the BBC’s flagship television current affairs show, her sleep is frequently disturbed by early-hour crises of conscience, replaying a question she wished she had, or hadn’t, asked the night before. Perhaps it sums up the unrelentingly self-reflective mind that has taken her to the top of the BBC tree. But I have to stop myself from messaging back to ask – in awe and envy – where she gets so much bloody energy from.

Rewind 12 hours and Maitlis bounces into our interview despite having been broadcasting the previous night until 11.30pm. When she arrives home on an average working day, the 48-year-old Briton says, she either responds to viewers’ emails or tries to kick back with a novel and a vodka on ice. After as little as four hours’ sleep, she will be up running with her whippet, Moody (named after the credit rating agency). And once we have wrapped up our chat, she will be off to a radio station and a TV talk show to promote the book she has somehow found time to write in between the mayhem of covering Brexit and Trump’s White House and raising two sons, Milo, 14, and Max, 12.

Admittedly, Maitlis has an extra spring in her step because she is here to talk about her “golden time” in her “spiritual home”, Hong Kong. It was a formative experience, about which she speaks with gooey nostalgia.

Fresh out of Cambridge University, she arrived in the city in 1992 – as Hong Kong was gearing up for the return to Chinese sovereignty after a century and a half of British rule – telling her mother she would be back in Britain in six weeks. She would end up staying for six years, finding a profession to which she’d want to dedicate her life and bagging a husband-to-be, investment manager Mark Gwynne (Maitlis would propose to him on a beach on millennium eve).

“I’m almost certain I wouldn’t have been a journalist if I hadn’t hit the ground at that moment and [amid] that extraordinary febrile atmosphere of tension and excitement and heat, all coming at the same time,” she says, over a flat white in a bar in London’s Leicester Square.

While one gets the sense that many Westminster journalists have few intellectual or cultural interests beyond the intrigues of parliament, Maitlis can boast the hinterland of a small country. The polyglot had landed in Hong Kong with a job tutoring Spanish, French and Italian, which left her plenty of free time to learn Mandarin, perform with a semi-professional theatre company and go on Buddhist meditation retreats.

With a “raging interest and not enough to occupy me” she signed up to a postgraduate degree at the University of Hong Kong “on, bizarrely, the bowdlerisation of Shakespeare”. At the same time, she was gripped by this portentous period in the region’s history and looking for an opportunity “to get into understanding the politics better”.

“It was almost like I was resisting the differences of Hong Kong and then it suddenly dawned on me. All the conversations, all the times I remember being there late at night and standing on rooftops, looking out and seeing China. It came crashing back into your brain that this was a complete clashing of cultures and worlds at a time that was just phenomenally exciting.”

Maitlis abandoned Shakespeare and got a job at RTHK, commuting to the radio studios from her home on Lantau.

In Britain, she is now a household name – having been on the BBC since 2001 – and was appointed as Newsnight’s first female lead presenter in March, leading an all-woman team. She co-anchors the BBC’s election coverage, too, and has interviewed everyone from Donald Trump, Bill Clinton and the Dalai Lama to Mark Zuckerberg, David Attenborough and Theresa May.

Maitlis is such a familiar face that she had a cameo role on BBC comedy series This Time with Alan Partridge and trended on Twitter as “queen of the eye-roll” after she did no more than give an exasperated sideways glance during a testy exchange on Brexit with Labour member of parliament Barry Gardiner. One viewer declared online: “We are all Emily Maitlis”.

She has also cornered the market in Britain on covering Trump’s presidency, with her illuminating interviews with former FBI director James Comey, alt-right strategist Steve Bannon and ex-White House communications directors Sean Spicer and Anthony Scaramucci.

The Spicer encounter went viral after Maitlis admonished him: “You played with the truth, you led us down a dangerous path, you have corrupted discourse for the entire world by going along with these lies.”

She collared Scaramucci – who survived in the job for only 10 days – on the White House lawn, while she was miked up and moments from going on air. “What part of Donald Trump is not elite: the business side or the inheritance side,” she asked. “How about the cheeseburgers? How about the pizza?” he replied, before an incredulous Maitlis hit back: “Everyone eats cheeseburgers and pizzas, what are you talking about?” Scaramucci retorted: “See, you’re coming across a little bit elitist.” The interview ended with the pair shaking hands and “the Mooch” addressing the camera: “Sorry I called you an elitist. But she was hitting me very hard!”

Maitlis insists that during her Hong Kong days, however, she was “a terrible journalist”, explaining, with a chuckle, “I made every mistake in the book.”

“I remember taking the ferry back every night with my best friend and a bottle of wine and somewhere between laughter and tears, crying about how badly the day had gone. And I think in a London environment, I would have just been chewed up and that would have been the end.”

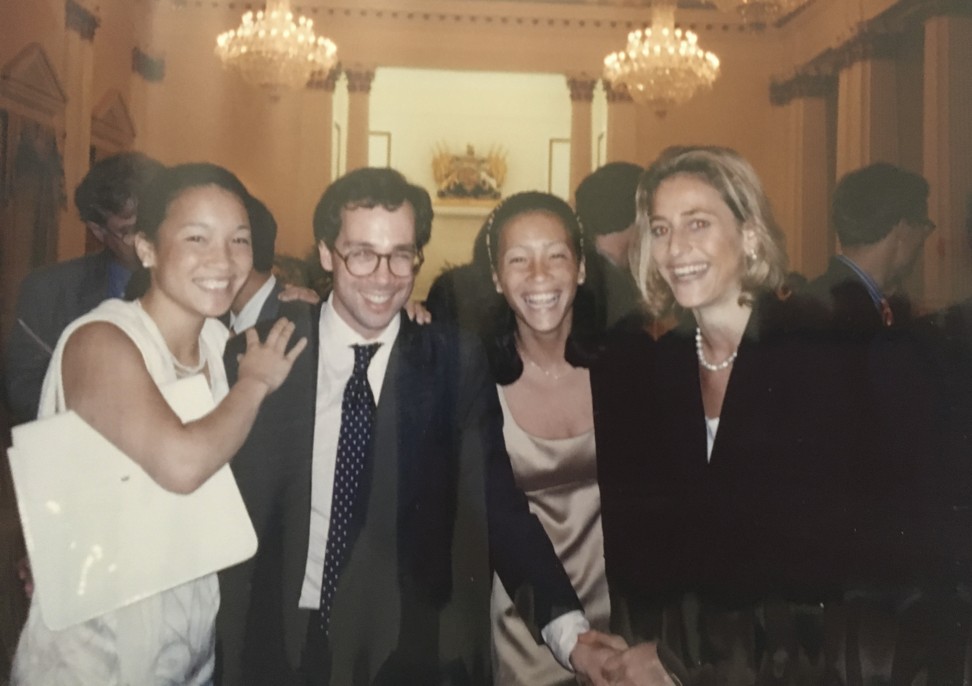

Maitlis moved on to TVB, where she was a producer of The Pearl Report, then NBC Asia – making documentaries in China, the Philippines and Cambodia, where she was even jailed for a few hours while trying to cover the dying days of the Khmer Rouge – before working as an assistant for Britain’s Channel 4 News, covering the handover from British to Chinese rule.

She was cool, efficient and enthusiastic. Judged by any number of fixers I’ve had in my 40-odd years working on the road, she was a breed apart

Veteran Channel 4 News anchor Jon Snow says he feels “humbled” to have been referred to as Maitlis’ mentor.

“She was cool, efficient and enthusiastic,” he tells Post Magazine. “Judged by any number of fixers I’ve had in my 40-odd years working on the road, she was a breed apart. She is extremely bright, personable and very well-informed and, to be honest, I was surprised that someone as good as her was available and that she didn’t have a job at one of the big banks.”

Maitlis recalls things differently.

“All I remember was coming up with slightly preposterous ideas and saying, ‘I’m going to get you to this island off the coast of Hong Kong but it feels like mainland China, I think it’s really important.’ Probably at the back of his mind, [Snow] was like, ‘I’m not going to a f***ing island. Stop trying to give me weird s**t features,’ but he was so gentle with me and so kind.”

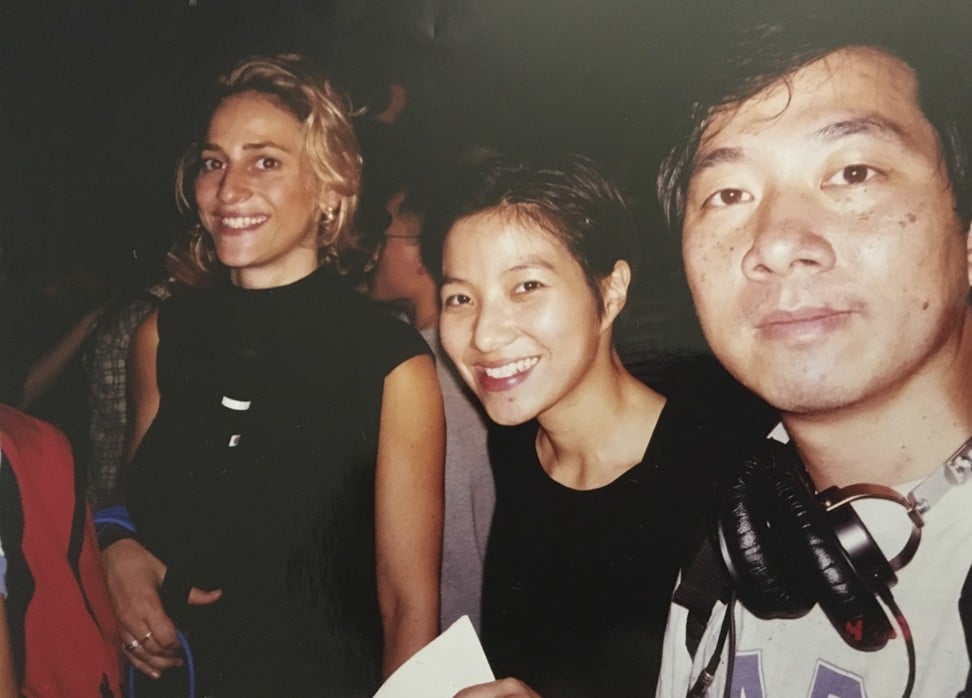

She also made documentaries for BBC Radio 1 on the music and club scene. Did she party in Hong Kong as hard as she worked? She pauses and grins.

“I think that was obligatory. It was just that sort of sultry heat and you’d stare out at the lights, a drink in hand. My partying was ecumenical, let’s say.”

Maitlis returned in 2014 to cover the “umbrella movement”, an experience she describes as “really heartbreaking”. In 1997, she remembers thinking, “‘It’s all going to be fine, we’ve just got to understand that it’s a lot of catch-up time for China.’ And going back and seeing what was happening there was profoundly shocking because essentially …” – a Chinese-speaking couple sits down next to us. “Oh that’s unfortunate!” she says.

“I remember how moved I was at how young the protesters were. It was kids in their school uniforms – trying not to miss out on their own futures. What I heard that night was that Tiananmen made a difference because lives were lost – and it was the most awful thing. The journalist in me went, and I just thought about the kids, and about my kids.”

Maitlis, who was born in Canada and grew up in a Jewish family in Sheffield, in the north of England, exhibits the analytical mind of her psychotherapist mother, Marion, and the forensic skills of her father, Peter, a retired professor of chemistry who escaped the Nazis as a child.

Today – along with electric blue nail varnish and a Snoopy T-shirt with the slogan “If I can’t bring my dog, I’m not going” (Moody’s not with her but she came anyway) – she is wearing a gold bracelet her father had made for her from a bangle her grandmother fled Germany with.

As she writes in her new book, Airhead, she was wearing the bracelet while she was covering the European refugee crisis in Hungary. Her main dilemma in the Budapest railway station was how she could distribute the soccer shirts, which had been her sons’ and that she had impulsively stuffed in her suitcase before leaving London, without them looking like “tacky TV bribes”.

She also covers the farcical moments. After touring poverty-stricken areas in India with Clinton, her eye was caught by a pashmina scarf in the hotel gift shop. When the former United States president walked in while she was trying it on Maitlis was so mortified that she wrapped the whole thing around her head as a disguise. Her embarrassment dissipated when she saw the tome he was flicking through was not on Indian history, but was the Kama Sutra.

Her book’s title is a subversive nod to the misogynistic stereotype of the female broadcaster – one Maitlis knows all too well. When she joined Newsnight as one of its main presenters, in 2006, parts of the press were convinced she had been promoted because she was an “autocutie”. Columnist Amanda Platell complained, “I don’t want to see a pretty dummy sitting there.”

Three weeks later, Maitlis attended an awards bash in what one tabloid called a “positively indecent” dress. Headlines referred to her as “The Boobsnight presenter” and blared, “Here are today’s news headlines … My boobs are trying to escape.” One profile was preoccupied by her “stewed prune eyes” while another speculated, “Her feminine attributes – rather than her journalistic talent – may simply stun her studio guests into silence.”

“Yeah,” she says softly. “I look back on that and I think it was appalling. But what was weird was that some people [at work] would come up and go, ‘Ooh, Emily, on the front page, ooh, what have you done?’ It was a sense that being a woman somehow made you feel a bit shameful. You know, ‘a TV woman’, like, the shame of it! So I hope that’s changed.”

More than a decade later – and in the same year she was covering #MeToo with an exclusive interview with Harvey Weinstein’s former assistant Zelda Perkins – Maitlis was still battling systemic sexism. In July 2017, the BBC was forced to publish the salaries of stars earning more than £150,000 (HK$1.5 million) a year. Only a third were women, the top seven were all men – and Maitlis was nowhere to be seen.

During a speech at a technology conference a day after the news broke, Maitlis quipped: “You’re [an industry] at the top of your game and if this continues, next year you’ll be able to afford a BBC man [to give the speech].”

How did Maitlis feel when she saw the disparity in black and white?

“I think mine was different, because I knew where we were,” she says, explaining she had been privately fighting her bosses for equal pay for most of the previous year.

But without the data, how did she know she was losing out? She hesitates, working out how she can answer without giving too much away. “I knew that, erm, for example, Jeremy Vine and I were literally doing the same job [during election coverage]. I was standing in front of a touch screen, he was in front of a [virtual-reality screen] and we were doing the same job with the same preparation. And there was a massive disparity in salaries.”

Did Vine tell her this?

“Erm, well, I knew. No. Funnily enough, a colleague on the team said: ‘You’ve got to sort this out.’ And I went in and tried, and I got told it couldn’t be sorted out.”

After a couple more questions, Maitlis drops her defences, revealing for the first time, “I … I went on strike actually. I just went on strike. I was like, I’m just going to quietly stay away until you sort out the contract, because it seemed like a more efficient way of doing things. I never made a big deal of it, never told anyone, it was just between me and them.”

How long did her industrial action last? “It was very quick actually – slightly too quick,” she says, with a wry smile – still clearly amazed at how it could be resolved seemingly only with the prospect of the publication of figures the BBC had fought so hard not to disclose. “You know, sunlight and disinfectant and all that sort of stuff. What’s that amazing phrase; most people don’t work against their interests if they don’t have to.”

It is this issue that will have Maitlis stirring at 3am to clarify. She’ll send me an email explaining she had been offered equal pay “literally days before the list”, but “I was slightly sceptical as you can imagine – and I didn’t want to suddenly appear on the list as if the gender pay gap had never happened”. She received “an extraordinarily generous” and “quite faith-restoring” phone call from colleague Evan Davis “where he basically said, ‘This is all wrong and we must put it right’”. She considered another job offer and bided her time “until after the list emerged – without me on it – and I could think about things more clearly”.

Her salary has now been raised to £229,999, making her the joint highest paid woman at BBC News.

The only other matter Maitlis is understandably reticent to discuss is the man who has been stalking her for well over 20 years. The former university friend was even able to write to her while he was in prison for breaching a restraining order and she has said she does not “ever believe it will stop”.

The experience has influenced her own reporting. She tells me that for several years, without fanfare, she has been covering mass shootings and terrorist atrocities without naming the perpetrators, instead focusing on the victims. But given the evident trauma the ordeal continues to inflict on Maitlis, it is a subject I am surprised to find receives a chapter in her book. Was this because she felt an obligation to shed light on the issue for other victims?

“No. It wasn’t actually. It earned its place there because I ended up doing a radio interview about it and so it was a way of me seeing what it was like to be on the other side of the microphone. Sometimes you forget what we ask people. It was only when I’d done it the other way round, I thought, ‘Oh God, this is horrific!’ It was really scary. And I felt it was important to include a sense of that vulnerability, maybe, yeah – that I’d been on the other side.”

Maitlis has described feeling “untouchable in Hong Kong; nobody was hunting me down”. I wonder to what extent this was the reason she went in the first place – and stayed for so long.

“I genuinely can’t tell you,” she says, pensively. “I think, subconsciously, I felt a lot freer there. When I look back at the sort of arc of it, I think, ‘Oh yeah, God, that was a sort of blissful time,’ and I knew he wasn’t going to find any of it.”

Hong Kong “taught me how to be brazen and to find my voice”, she says. It is somewhere “I have always felt I owed”. She relishes memories of “gay clubs with gay friends in ridiculous gold lamé – being told you looked great when you looked atrocious!”

“The gold lamé was quite common, actually,” she admits. “I indulged in fashion in a way I probably wouldn’t have done here. I wore one outfit – it was this amazing crushed silk and you had to tie it in knots so that, when you opened it, it was like hundreds of creases and crushes. I remember my friend saying, ‘You look like a tree in that’, and we had a discussion about whether it was a bad thing to look like a tree or whether it was a profound thing to look like a tree.

“But, actually, it probably said a lot about my state of mind that none of that mattered – it was just all an adventure.”