Nine of the best books to read this summer, wherever you go on holiday

- Find answers to existential questions, learn how to arm yourself in the fight against climate change and explore the world beneath your feet, all in the pages of a book

- Chinese novelists Gao Xingjian, Can Xue, and Chi Zijian among the writers featured

The archetype of the summer book is the steamy blockbuster, stuffed in a bag alongside sunglasses and sunscreen. Whether your preference is romance or action, self-help or self-improvement, the story should be diverting enough to fill your suddenly freer time, but not so diverting that one can’t drop it for a swim, to play with the kids or head to the bar. It should be entertaining enough to enhance the mood of escapism, but not so lightweight that you doze off the moment you open a dog-eared page.

A change of environment

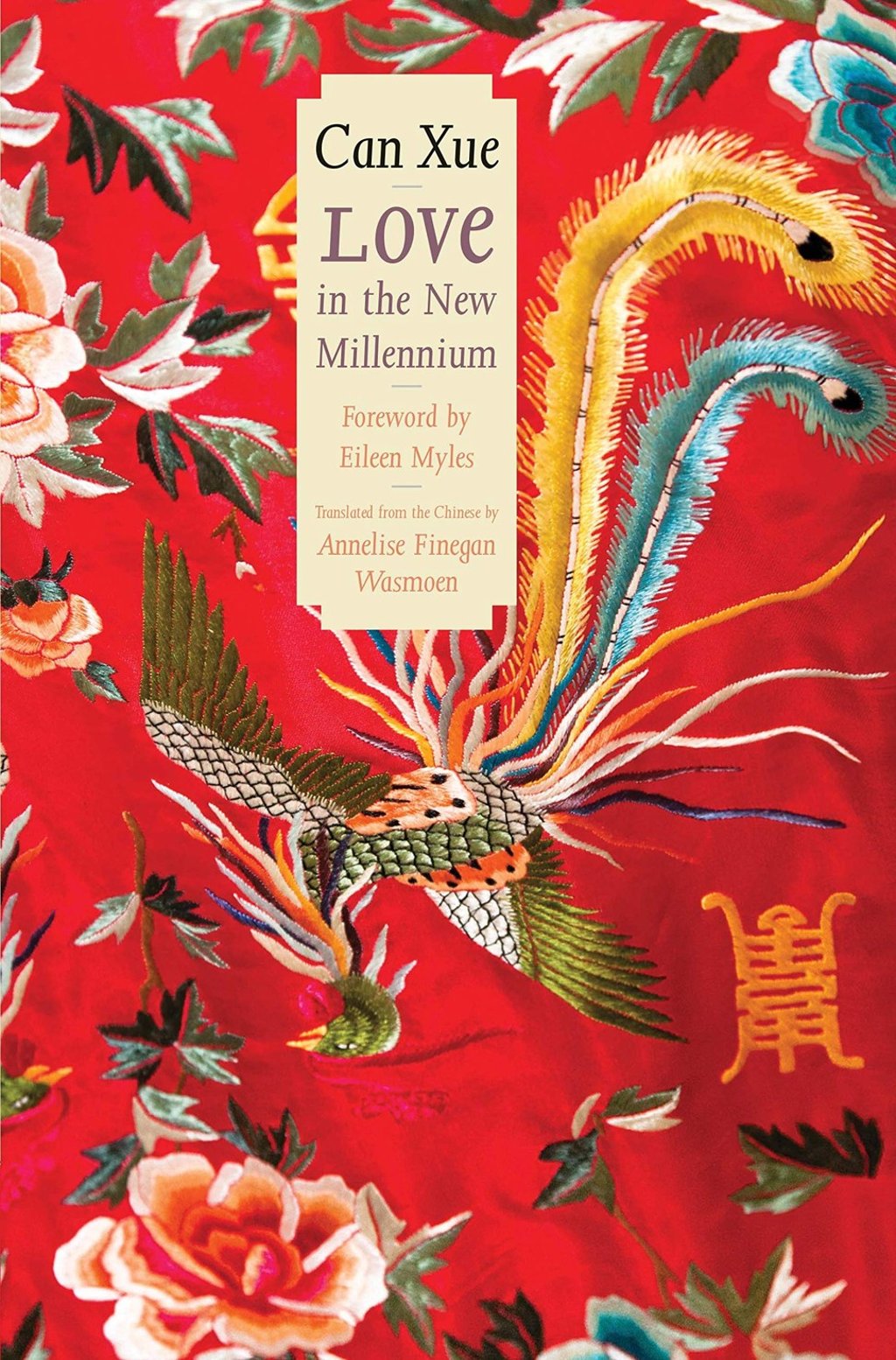

Love in the New Millennium (2013) by Can Xue

The best books, like the best holidays, broaden the mind. Both transport you out of the everyday and return you changed, hopefully for the better. Few modern novels have united these twin ambitions to more startling effect than Can Xue’s extraordinary Love in the New Millennium. A tale of many women, perspectives, tones and settings, its unifying theme of change is personified by Xiao Yuan, who takes a holiday from her life after her husband, Wei Bo, is sent to prison. “She wanted to become a different person through a change of environment,” Can writes.

In many respects this seems a natural decision for a former geography teacher who loves nothing better than the long train journeys demanded by her somewhat vague work. But it is still a bold move: Xiao may spend a great deal of time away from home, but she always returns. “I like to travel,” she tells a blind man named Cricket, riding in the same train carriage as her. “Making a journey is the same as clinging to one place. If you settle down in your hometown, it feels instead as though you are drifting along.”

With her husband in prison, however, she no longer sees any impediment to joining her (unrequited) lover, Dr Liu, in his hometown of Nest. A quest to find someone, Xiao learns, is “a good reason to travel”.