How composer and DJ Gabriel Prokofiev is bringing classical music to a young audience

- The Russian-British composer, producer, DJ and artistic director of London nightclub Nonclassical talks about growing up with his father, artist Oleg Prokofiev

- He says that, though his grandfather was composer Sergei Prokofiev, there was no pressure to go into music

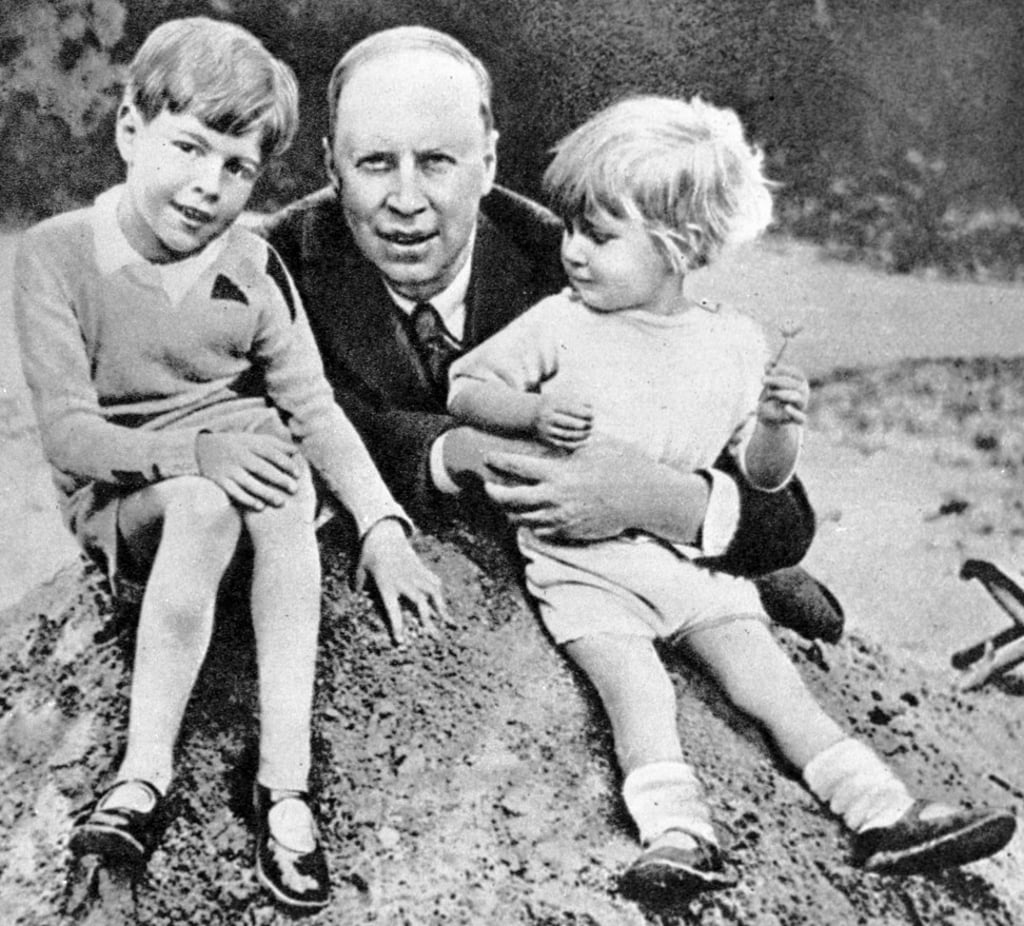

Famous fathers: My father, Oleg Prokofiev, was a Russian abstract painter. In the 1950s and 60s, abstract art was forbidden in the Soviet Union, so he couldn’t exhibit his work or live as an artist. His second wife was Camilla Gray (a British art historian), who he met in Moscow but had to wait seven years for permission (from the Soviet government) to marry. She moved to Russia and they had a daughter, Anastasia, but a year later Gray fell ill with hepatitis and died.

My father came to England for her funeral and never went back to Russia. He got a fellowship as a resident artist at Leeds University and met my mother (Frances), who was a student there and an artist. They started a family and I was born in London, in 1975. There were five of us kids growing up in Blackheath. It was a lively, creative household. My father was always working on his art and playing loud minimalist music, like Philip Glass, or jazz or Bach.

Striking a chord: When I was 10 years old, I began writing pop songs with a friend, Nathan Cooper. We would get together at the weekend, sit down at the keyboard with a blank page and an hour later we’d have a melody and some chords. We performed a song in school assembly and everyone liked it. We were hooked. By the time we were 12, we’d formed a band with some friends, and by 13 we were doing concerts around Blackheath.

Then there came the chance to write classical pieces at school. I wrote a piano piece and the teachers were impressed. For the first time, I thought maybe I could do classical music. It was so far removed from what my grandfather had done that I didn’t compare it to him, didn’t feel any pressure. As I got older, I felt self-conscious about the Prokofiev name and wanting to do music and shied away from composing for several years.