Born in Stanley’s POW camp, George Cautherley is a true Hongkonger

- George Cautherley, former vice-chairman of the Hong Kong Democratic Foundation, was born in a prisoner-of-war camp and recalls a bomb landing near his play area

- Thanks to a DNA test and a sleuthing PhD student, he recently discovered he is a descendant of the prominent Heard family of Hong Kong

Losing everything: My mother was born and raised in Shanghai and my father went to Shanghai in 1926 to work for the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. They met briefly in 1931, when my mother joined the bank, but they didn’t get together until 1937, when they were both living in Hong Kong. My father was still with the bank and my mother had been evacuated because of the Japanese hostilities in China. They married and lived on Peak Road (now Mount Austin Road), which is where I was conceived.

In 1940, women and children were evacuated to Australia, but my mother didn’t go as she’d signed up as a volunteer nurse and was considered part of the essential services. When the hostilities broke out, the British mounted guns just below Mount Davis Road and pointed them out to sea because they expected the Japanese invasion to come by sea.

When the Japanese invaded from the New Territories, they turned their guns around to fire over Mount Davis and Mount Austin into the New Territories, but they’d forgotten to install a concrete base and the guns had sunk and clipped off the corner of my parents’ apartment building. The British Army gave them seven minutes to clear the building, and then blew it up, so my parents lost everything.

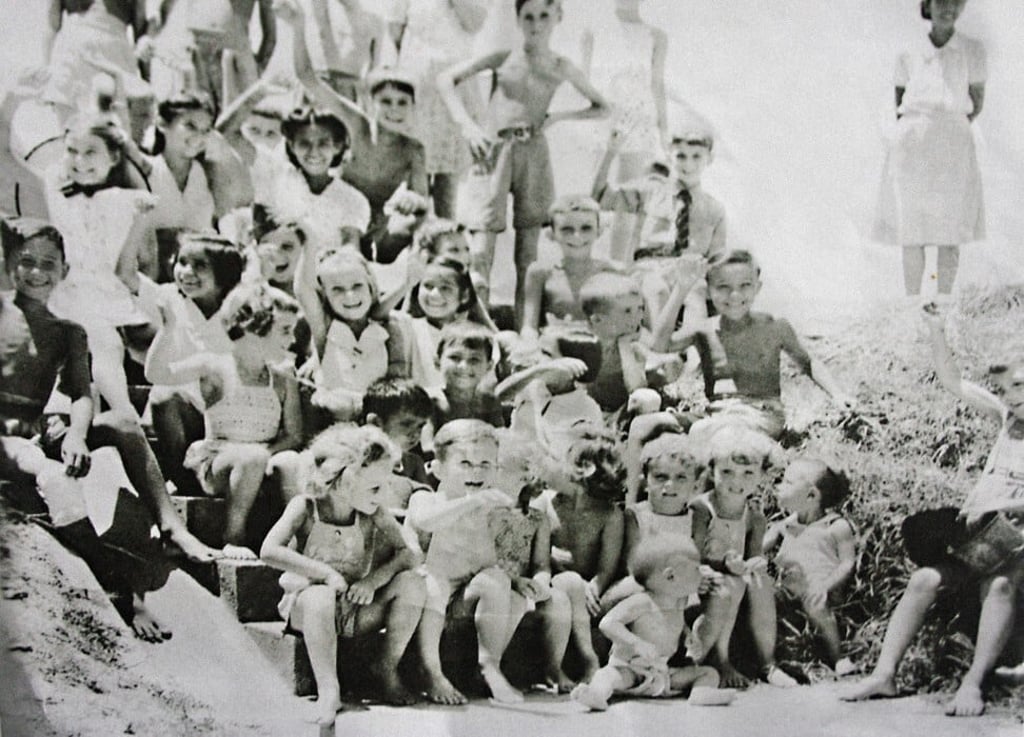

Camp life: HSBC was asked to keep operating, so half their staff were retained and the rest went to fight. My father was among those retained and was at the bank when war broke out. My mother was at Bowen Road British Military Hospital. They were sent to Stanley internment camp, which is where I was born in September 1942. My father was ill much of the three years we were there.

We used to be allowed to go down to Tweed Bay in Stanley to paddle in the water. The steps down to the beach were very hot and as I didn’t have shoes some poor skeleton of a man had to carry me on his back. I remember playing outside one day and my mother grabbing me and taking me inside. I later learned that was when the Americans bombed and missed and hit a bungalow not far from where we were.