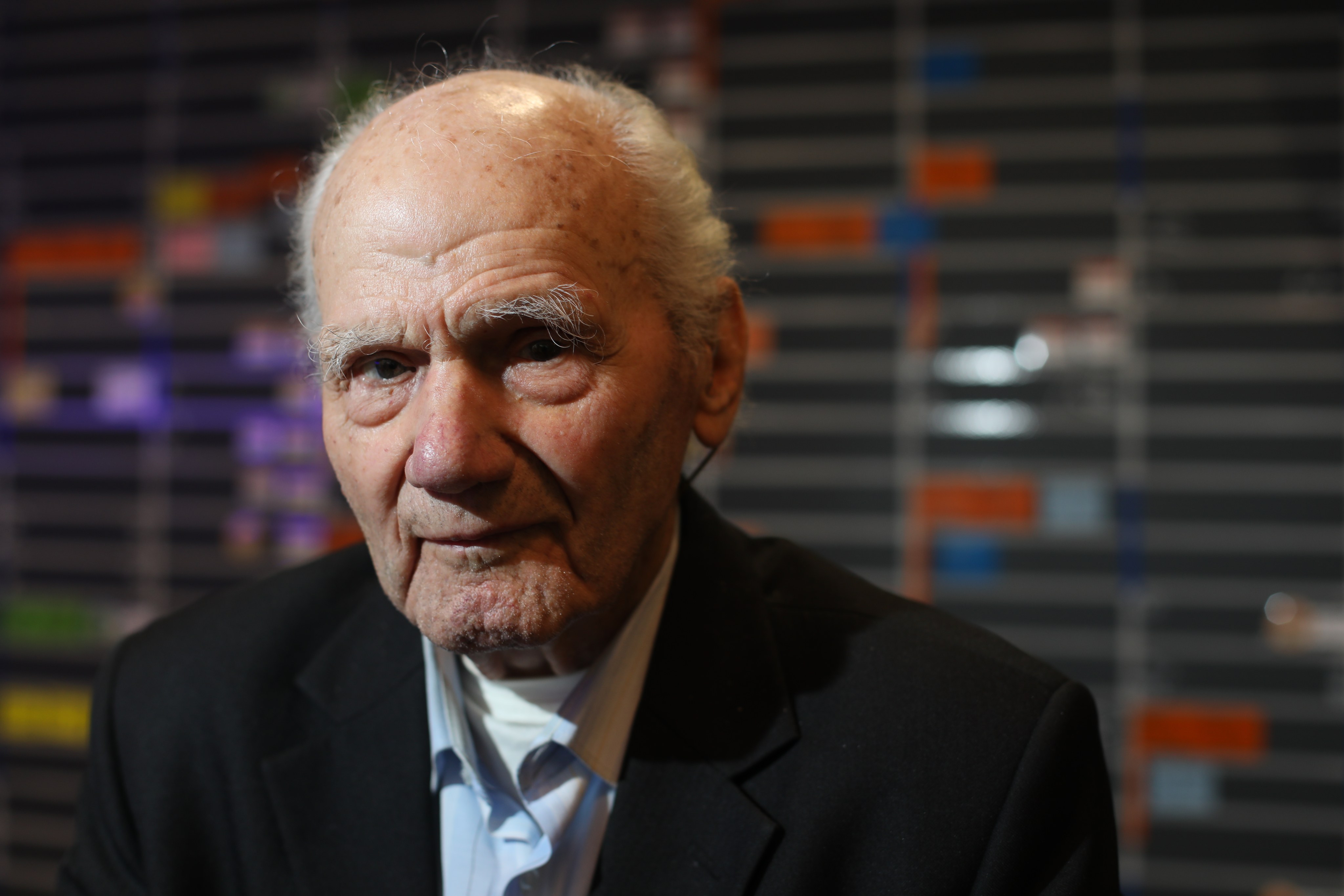

- Andrei Iwanowitsch, 98, a survivor of the Nazi Buchenwald concentration camp, talks about nearly dying, and how in old age travel opened up his ‘narrow’ world

I was born in 1926 in a small village called Budionovka, in northern Ukraine. I was the eldest of four children.

When I was six, my mother died of typhus. My father remarried and had two more sons.

My parents worked on a collective farm. Everyone worked at least 100 days a year on the farm and in return we were given food in the autumn and winter. Every family had a small strip of land to grow vegetables.

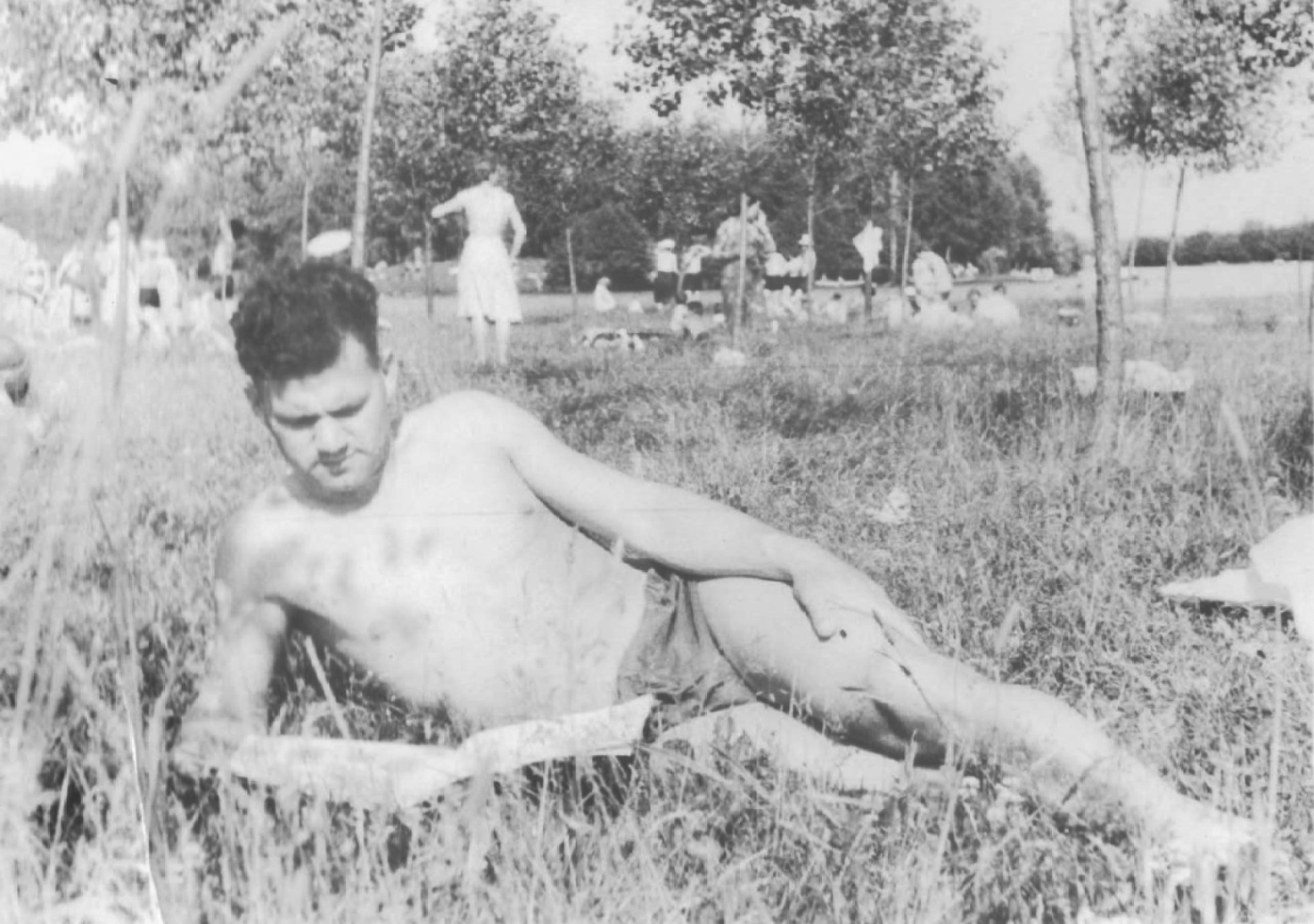

We all worked, regardless of our age. My job was to take care of the horses. I went to a village school. It was a simple, barefoot life.

Nazi invasion

In 1941, the Germans invaded Ukraine and my father was drafted into the army. He died on the front lines. Not long after, my stepmother was caught in German gunfire and was killed on the spot.

Soon our neighbourhood fell under German occupation. I was 16 and as the eldest I was responsible for us children. I got a backpack and walked to the nearby villages to ask for food.

The other villagers were also poor, but they gave what they could, sometimes just potato peelings.

I was on the way home to my siblings when I was stopped by the local police. They checked my backpack and said, “We know you want to feed your siblings. We’ll send you to Germany where you can earn money and send it back to them.”

Forced labour

I was taken with others even younger than me to the train station and we were forced onto carriages. The wagons were packed, and we were all very afraid.

They only spoke the truth: anti-Nazi resistance an example of moral courage

When we arrived in Leipzig, we were taken to a market where farmers picked the people they wanted to work on their farms as forced labour.

I was in a group that was taken to a transit camp. There were only about a dozen kids like me, the rest were all adults. In the mornings, we were given breakfast and then put on a tram and taken to an ammunitions factory called Hasag.

At Buchenwald … Many of us were skin and bones. … I don’t know how I survived, but I did.Andrei Iwanowitsch

The kids mostly did the cleaning up and the adults worked on the machinery. We kids stuck together and would sing the Soviet songs that we knew. There was no lunch.

At the end of the day, they took us back to the camp and gave us soup made from rotten cabbage. We slept on three-deck bunk beds. I had to climb to the top bunk and the adults were on the lower bunks.

From the camp to the factory and back to the camp – that’s how I lived for one-and-a-half years.

Under interrogation

The Germans had a record of who was literate. I’d done seven years of school and it may have been because of this that I was moved to work in the spare-parts department.

I had learned some German at school and after a year at the camp I could make out what they were saying. Although I could understand a lot, I spoke very little German.

I had friends working in the ammunition factory where there were a lot of accidents because of sabotage, putting nails in the machinery and things like that.

The children were suspected and were gathered together for an interrogation. Because they sometimes visited me at lunchtime, I was also under suspicion.

We were gathered to go on a death march. We walked towards the quarry where we would be shot and then buried. We marched for two days.Andrei Iwanowitsch

I quickly realised that the Polish translator wasn’t accurately translating what we said to the German officers. I spoke directly to the German officer and he understood what I was saying, and we were released.

After that, the interrogation continued, but only with me. At one point, the Gestapo officer left his pistol on the table and walked to the window. I was sure it was an empty pistol and it was a test to see if I would take it. I didn’t.

After that, I was sent to a Gestapo prison in Leipzig for two months. To this day, I’ve no idea why I was sent.

Deadly beatings

After two months in prison, I was moved to another prison briefly and then sent to Buchenwald (concentration camp) at the end of 1943. My prison number was 19852.

We worked in the day, sometimes in the quarry carrying stones. On the way to work, we had to pass through a gate. The SS officers standing on either side of the gate beat us, so we passed through as a group, with the adults protecting the younger ones.

If someone was struck directly, they’d fall down dead. If I’d been hit, I wouldn’t have survived.

The food at Buchenwald was even worse than at Hasag. The European prisoners received packages from the Red Cross, but not the Soviet prisoners. Many of us were skin and bones.

Uncovering the truth behind a Chinese-American soldier’s World War II death

When I had a chance to walk through the camp and pass the barracks of the Czech and French prisoners, they’d sometimes give me a little bread and butter. I don’t know how I survived, but I did.

Death march

On April 12, 1945, when the allies began approaching, we were gathered to go on a death march. We walked towards the quarry where we would be shot and then buried.

We marched for two days. The SS guards were accompanied by vehicles and they walked in shifts. After three or four hours, we’d have a break and sit down and wait for the guards to finish eating.

I ran towards a small bush, but I saw someone was already hiding there. There was a spray of machine gun fire. The person was killed. That could have been me.Andrei Iwanowitsch on a close call

They’d toss bones and bits of bread aside as they ate. Sometimes one of the adults, crazy with hunger, would try to snatch a bit of discarded food, but before they could reach it a guard would shoot them.

The adults kept to themselves, but we children stuck together. We walked in groups of about four and supported each other.

At one point I saw stars in front of me and fainted. My friends took me on either side and helped me keep going. After about five minutes, I was OK.

When one of the adults collapsed, everyone walked over them and then there would be the sound of gunfire. After they were shot, their body was loaded onto the vehicle so as not to leave a trace.

Americans, Americans

We suddenly changed direction, probably because the allies were approaching, and they marched us towards another quarry. We saw low-flying aeroplanes approach and dropped to the ground.

On the left, I saw grass and on the right were meadows. From behind us came a tank with a machine gun loaded on the front. As it started shooting at us, people jumped up and shouted, “Americans, Americans!”

A wave of euphoria spread through us and we were all on our feet. The SS guys threw their guns to the ground and ran towards the fields.

It’s hard to describe the scene. People were crying, shouting, laughing and hugging, there was a huge emotional outburst.

Some people jumped on the SS guys and tried to beat them while other SS guys were caught by the Americans.

Close call

The Americans told us to walk to the next town, which was 2km (1.3 miles) away. On the way there, German planes passed overhead, and they fired at us with machines guns.

We ran for cover. Some people hid under the tanks. I ran towards a small bush, but just before I reached it, I saw someone was already hiding there. There was a spray of machine gun fire and the bullets kicked up dust as they hit the dry ground.

The person hiding under the bush was killed. That could have been me. I was just a few metres from death.

We watched the aeroplanes fly off and carried on towards the city. When we got there, it was deserted. We went into the houses and salvaged pickled food.

I quickly realised it was impossible to get a job if I told people I’d been in Buchenwald, so I kept silent.Andrei Iwanowitsch on looking for work after his discharge from the Soviet Army

The adults got drunk with the American soldiers. They couldn’t speak English, the only thing they could say was, “Roosevelt, Stalin!”

During the two weeks we were there, the Americans encouraged us to emigrate to America, the UK and even Australia. I didn’t want to emigrate.

On May 1, I turned 18, and four days later I was drawn into the Soviet Army. Those who were younger or a lot older were sent home.

There weren’t enough soldiers, so instead of just two years’ service, I served six years in the 120th Guard Unit in Minsk, Belarus.

Finding love

I was released from the army in November 1950. I had no family, so I decided to stay in Minsk. I quickly realised it was impossible to get a job if I told people I’d been in Buchenwald, so I kept silent.

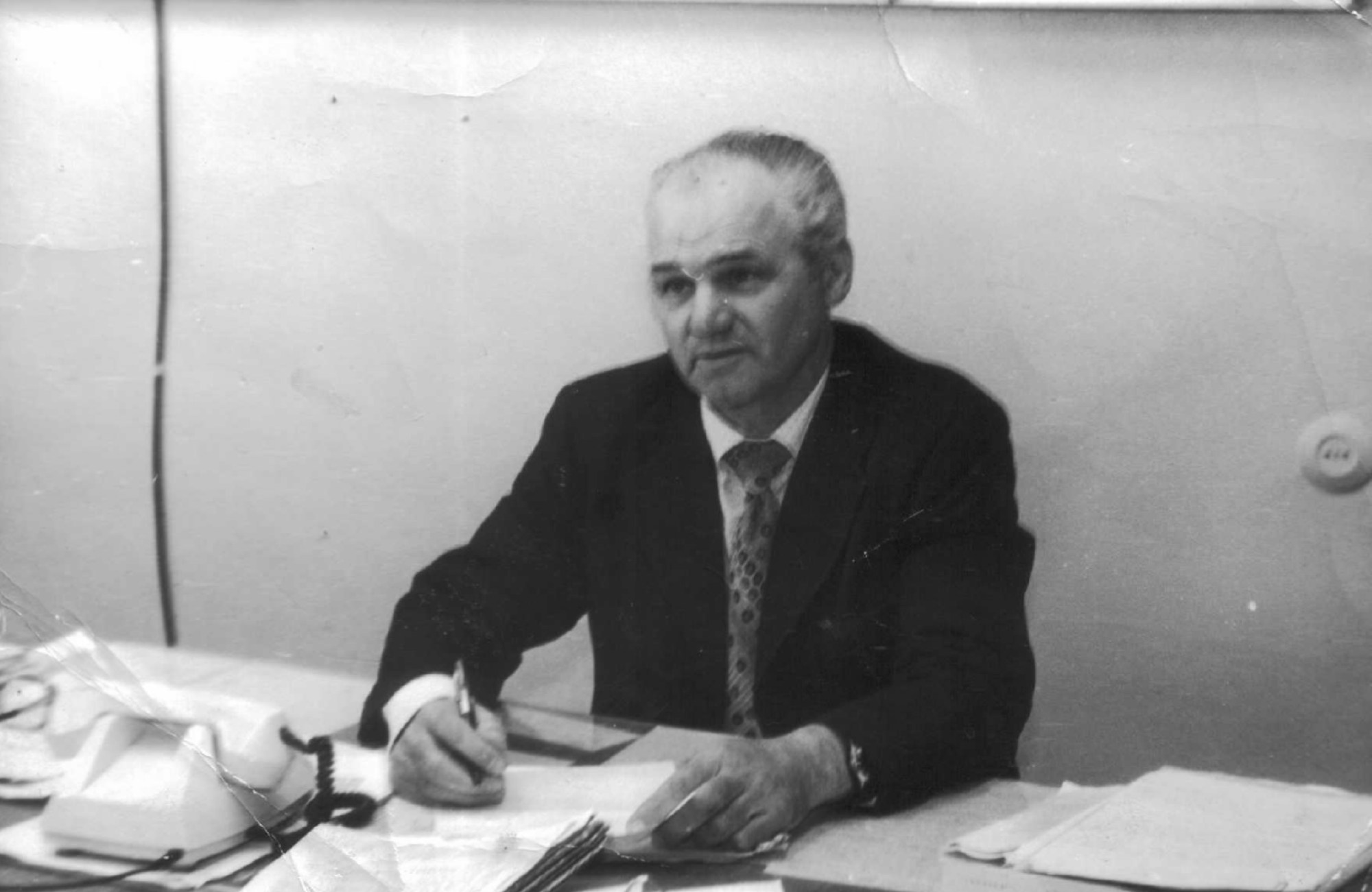

I got a job at an engineering company called Amkodor and four times a week I went to evening school. I met my wife, Claudia, in the summer of 1953 and we married three months later. She was the love of my life, we had two sons.

When I finished my schooling, I went to the Belarusian National Technical University for evening classes. I graduated in 1960 and got a job in an engineering company where I worked for 35 years until I retired.

My wife died in the 1980s. Later, I had a girlfriend, Galya, but she has also died now.

Opening up

In 2005, I was invited by the German government to the Buchenwald Commemoration Day.

I had spent my life not talking about Buchenwald, but the invitation meant that I could speak about what had happened more openly.

Aside from two years during the pandemic, I’ve been to the commemoration day every year. Each year fewer people attend – from 500 people, it’s now just me left. I will go this April.

When I’m there, they treat me well and show that they care about me. I’m very glad that there has been this reconciliation.

Captured on film

My life has been very narrow. I went from Buchenwald to the army and after that I worked, learned and studied hard. I didn’t see anything of the world.

In 2012, I met (Hong Kong-based German business representative) Hannes Farlock. We became friends and he made a documentary about me, Ja, Andrei Iwanowitsch. Hannes invited me to Hong Kong in February. It is incredible to see this super city. Even in 150 years, Belarus will be nothing like this city.

My wife, children and siblings have all died. I’m the only one who is still alive. I’m grateful for every day that I have. I feel very content that in my later years I have this possibility to see the world.