Chinatown in Kuala Terengganu: from rot to a riot of colour, as murals give old town on Malaysian coast new life

The ‘five foot alleys’ of the historic Chinatown on Malaysia’s east coast, a cultural melting pot for centuries, have been transformed by themed murals celebrating the settlement’s history and its great and good

The car stops beside the coastal highway to Kuala Terengganu. Ismail jumps out and trots up to a tree. He scrapes at the bark and jogs back with a strip of it.

“This is gelam bark,” my guide announces. “It’s used to join the planks in boat making here.” The off-white substance has a curious springy texture.

Within the hour we have rumbled onto a wooded island at the mouth of the Terengganu River and stopped at a boatyard. In an open-sided shed stands a hull under construction, its chestnut-coloured wooden panels tightly fixed and beautifully curving towards a high prow.

“You see those white lines between the planks?” asks Ismail, clambering to a spot where he can touch one. “That’s the gelam bark. They don’t use anything else, not caulking or glue, just that stuff to fix the hull together. They make the boats without any plans, just using knowledge passed down from father to son.”

The image of the finished boat, the bending of the planks, the carving of the dowels, the pounding with mallets, all are etched into muscle and brain.

Now a base for just a handful of builders, with wealthy foreign customers keeping the best artisanry afloat, Duyong Island was once the vigorous hub of boatbuilding on peninsular Malaysia’s east coast, blessed with rich fishing grounds and busy trading links.

The fishermen and traders needed seagoing craft and there were 100 or so boatyards on the island. To ancient Malay designs the craftsmen added innovations from the distinctive vessels of the traders from China, the Indonesian islands, Indochina and Siam who landed on these shores, as well as those of the Arabs, Indians and Europeans who visited.

Chinese chronicles record regular trade with the Terengganu coast from as early as the 10th century, and undoubtedly the most impressive visit was that of Admiral Zheng He’s fleet in the early 15th century.

Some time after that, Chinese traders began to settle in Kuala Terengganu; by the early 18th century, there was a well-established Chinese community in the port, recorded by a British trader in 1719: “[...] about one thousand houses in it [...] above half peopled with Chinese, who have a good trade for three to four Junks yearly”, with pepper as the main export.

The five-foot ways lead on to facades ranging from brilliant renovationsto crumbling masonry with weeds sprouting from the cracks, the odd faceless modern block rudely muscling its way in.

At one point there is a burst of “digital batik” gown shops, the ankle-length dresses – computer-designed and industrially printed – clinging to serried ranks of headless mannequins. In this kaleidoscopic stretch, ladies swaddled in more modest robes peruse the dazzling goods with a view to making a big splash at their next social event.

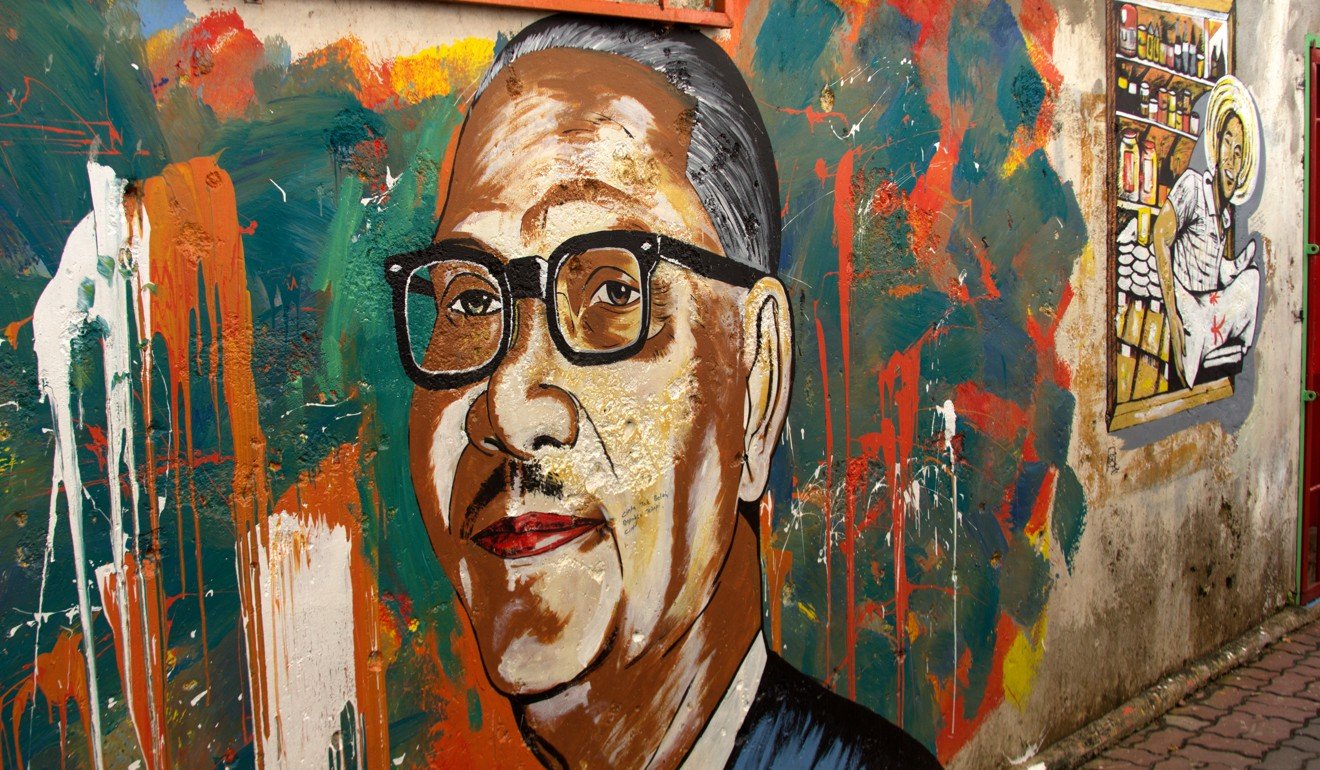

Perhaps the most compelling is an alley adorned with portraits, ranging from evil-looking cartoon characters to the benign face of Tunku Abdul Rahman, the well-loved first prime minister of the Republic of Malaysia. Much simpler is boldly colourful Eco Lane, with its mini-jungle of potted plants and one building walled with corrugated iron panels painted in a patchwork of bright primary colours.

Tauke Wee Sin Hee Cultural Lane is named for the most successful trader of the early 20th century and is located beside his principal premises of old, where his granddaughter still lives.

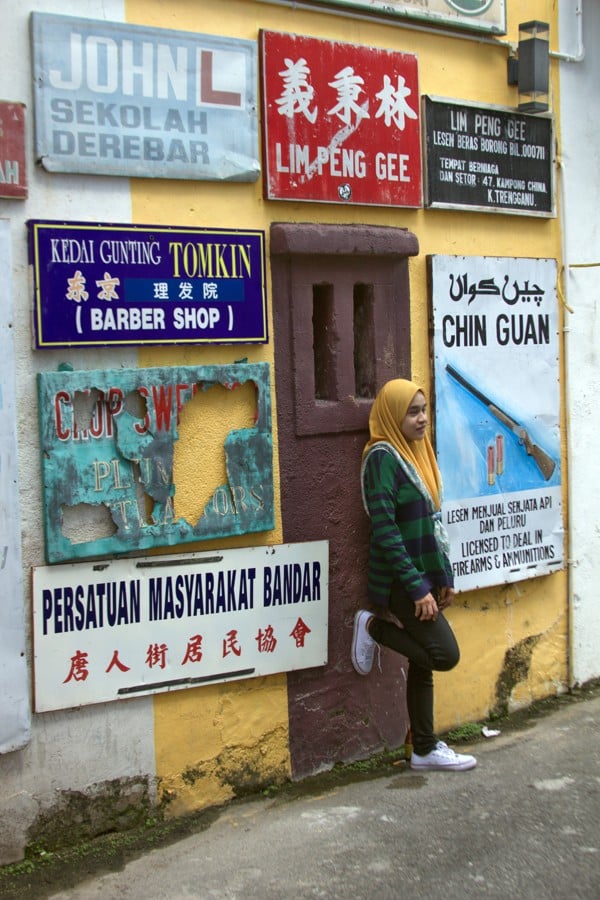

Wee Sin Hee owned 20 shophouses, seven trading ships and large rubber plantations, and was a distiller of liquor. The alley features a wall covered with vintage shop signs, a nod to the multi-faceted enterprise of local personalities such as Wee Sin Hee.

Narrow Turtle Alley honours a species that once visited Terengganu’s beaches in their thousands to lay eggs. Leatherback turtle numbers have since been decimated by harmful fishing methods, egg snatching and tourist harassment. Ceramic mosaic turtles dot the ground and walls of the alley and signs suggest ways in which the species can be protected: don’t eat their eggs, for example, and don’t throw plastic bags into the sea, where turtles mistake them for jellyfish and choke on them.

Red, yellow and blue umbrellas float above Payang Memory Lane, symbolising unity in diversity, a message constantly driven home to Malaysia’s conflicting ethnic groups. And above Malay-themed Haji Awang Besar Lane hang intricately painted wau bulan kites, emblematic of Malaysia’s east coast.

Lovers’ Lane has a wall where the enamoured fix padlocks scrawled with their names: Yasmin has the hots for Amir, apparently – or at least she did, when she left her lock of love.

Local author Awang Goneng, in a paean to his home state titled A Map of Terengganu (2011), has a message for any local developers intending to do away with this last vestige of the old city.

“Why hold onto our past? Well, because the past is us, for one thing, and it is our history and our story and you will not get the same resonance and hear the same sounds rebounding from the readimix mortar that you pour and shape into your gleaming shopping malls.”