Xiao Zhan scandal – why millions of Chinese shoppers boycotted Piaget and Estée Lauder because of homoerotic idol fan fiction

How an irrational cyberwar against fans of Chinese idol Xiao Zhan sparked a boycott of luxury brands associated with him, including Piaget and Estée Lauder

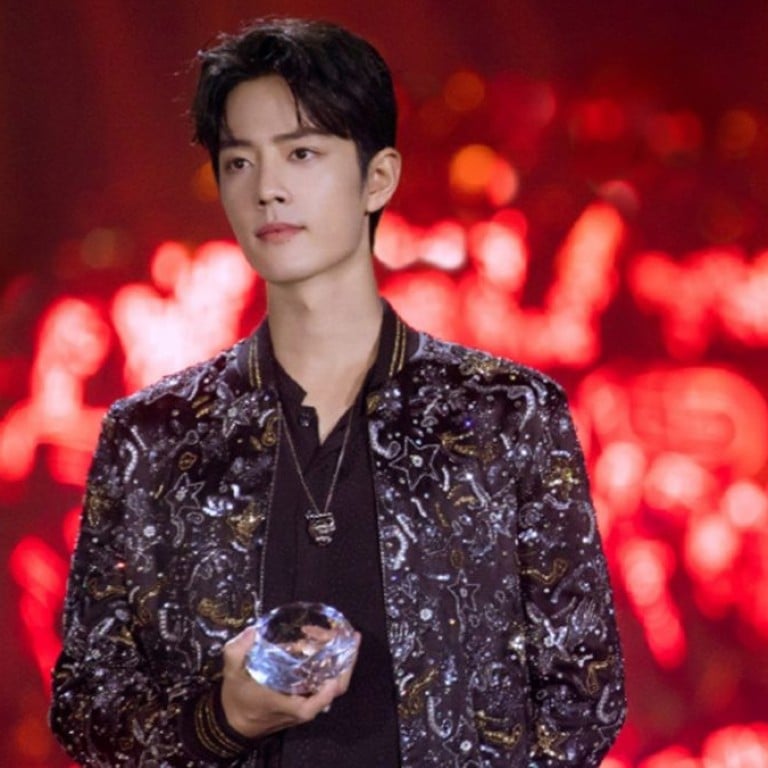

Chinese pop idol Xiao Zhan was embroiled in a controversy over the weekend that rocked Gen Zers all across China’s internet. A cyberwar against Xiao fans eventually led to a boycott of the brands the idol campaigns for, including Estée Lauder, Piaget and Cartier. While China’s idol economy remains a lucrative territory for international brands, this incident has revealed its dark side, and an intensified culture of cyberviolence, irrational fandom, and digital censorship are all risk factors that brands now have to face in this increasingly volatile market.

On February 24, a Weibo user published two article links to a piece of fan fiction titled Falling, which depicts the male idol Xiao Zhan as a cross-dressing teen falling in love with another well-known idol named Wang Yibo. Xiao’s fans were unhappy about having their favourite idol’s identity used in homoerotic literature and viewed it as “tarnishing Xiao’s image”. Many fans then decided to report the fictional content to Chinese authorities as “underage pornography”, hoping it would get it censored.

Things escalated quickly after A03’s takedown. Enraged by Xiao fans’ censorship plot, millions of free speech activists began boycotting the dozens of brands Xiao campaigns for, including Estée Lauder, Piaget and Qeelin. But they’ve gone further than the usual boycott by promoting competitors of Xiao-promoted brands, crashing Xiao-sponsored brands’ customer service lines, and pressuring those brands to end their collaborations with Xiao. So far, the Chinese Weibo hashtag #BoycottXiaoZhan has exceeded 3,450,000 posts and 260 million views.

Though Xiao’s PR team apologised on Weibo and urged fans to “be more rational”, the damage has been done. The idol’s public image has gone from pop-culture sweetheart to “lowbrow” celebrity with crazed fans in a matter of days.

As of today, Estée Lauder and Piaget’s Weibo profiles have been invaded with thousands of comments like “change the idol, or we boycott you”. And though no brand has taken the step of terminating their collaboration with Xiao yet, brands like Olay and Crest have taken product campaigns that use the idol’s image completely off their e-commerce sites.

Before this incident, China’s idol economies were known as a key growth engine that drives big spending on luxury brands. A collaboration with idol Kris Wu reportedly contributed 20 per cent growth to Burberry’s second-quarter performance in 2016. And over last year’s 11.11 shopping fest, Estée Lauder sold out US$1.22 million (8.52 million yuan) worth of Xiao Zhan-themed products on its Tmall store in only one hour.

Chinese idols have hard core fan bases with highly organised operating systems in place. But unlike Western fans who look up to idols, fan communities in China see themselves as “mother figures” who nurture their idols and their careers. This desire to nurture leads Chinese fans to have unusually frank attitudes about their idol’s commercial collaborations.