Are K-pop girl groups like Blackpink too objectified? Park Jin-young and Orange Caramel put out sexy music videos while GFriend went for an innocent look – but both approaches have problems

- In her new book Is Being Called Goddess a Compliment? pop music critic Choi Ji-sun takes a deep dive into how K-pop idol girl groups are produced and consumed

- Miss A and Loona were more progressive with the ‘girl crush’ image and showcases of diverse womanhood – but the whole industry needs to help create real change

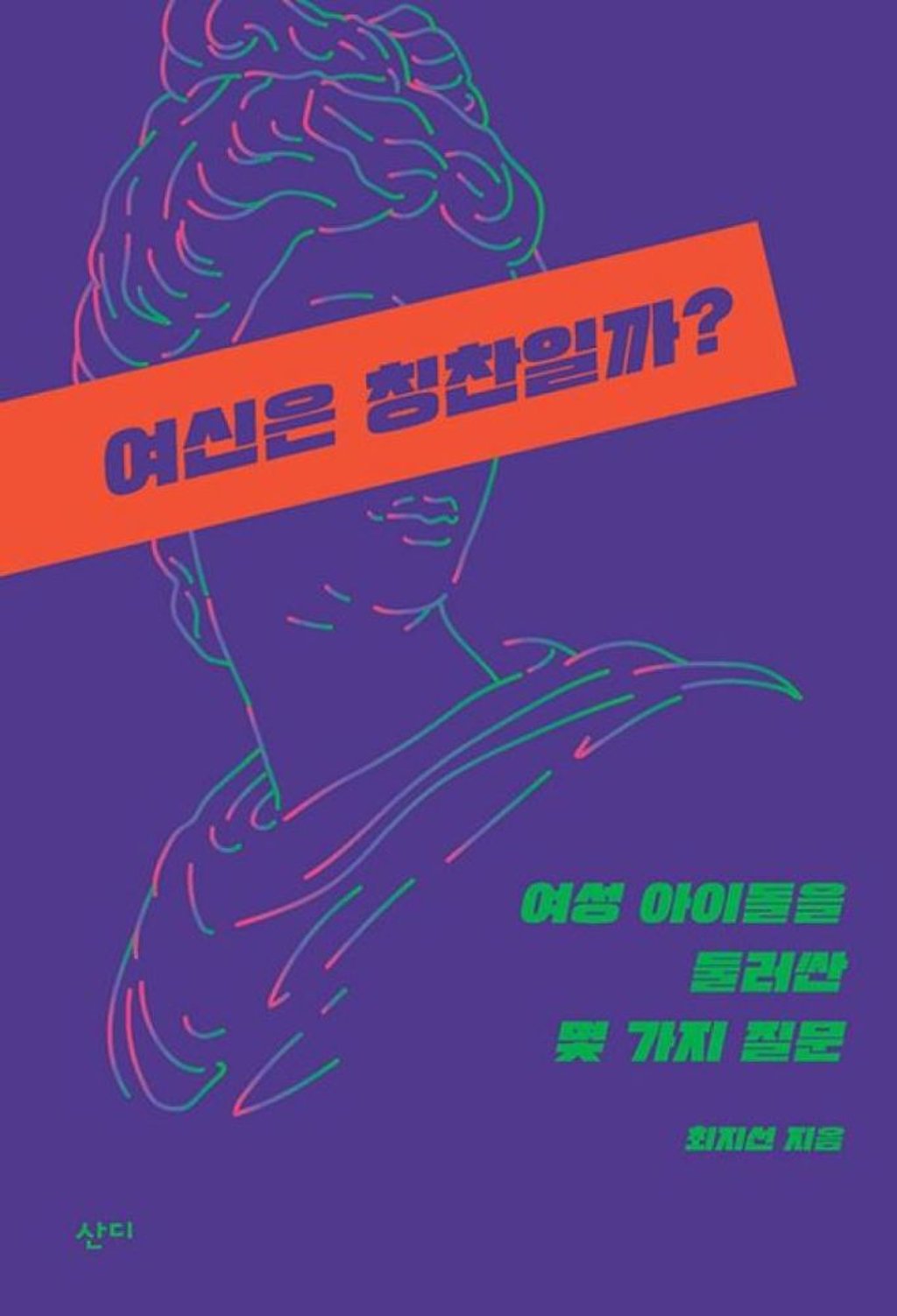

How do female K-pop idols typically appear on camera? What are some of the archetypal looks associated with girl groups? Why is it rarer for female idols to produce their own songs? And is being called an “elf” or “goddess” really a compliment for female idols?

These are some of the questions address in a new book, entitled Is Being Called Goddess a Compliment?, in which South Korean scholar Choi Ji-sun carries out a thorough examination of the way K-pop idol groups – especially girl groups – are produced and consumed, delving into the unseen gender dynamics within the music industry along the way.

Based on her 20 years of experience analysing popular music, Choi raises dozens of questions regarding topics that range from colour schemes, adjectives and costumes typically associated with female idols to their relationship with the idea of femininity.

“Studying and writing about the theory and history of pop music, I naturally came to pay attention to the K-pop idol business. As a woman myself, my interest in looking into the lives and music of female artists was also reflected in the process,” she says, explaining her motive for writing the book.

By both the media and fans they are built up into idols, and sometimes objects of romance, perceived by many as an ideal human beings with no apparent moral flaws.

But Choi stresses a clear difference between male and female idol groups in terms of the images they seek to achieve and their positions within the industry.

“I wanted to examine how those elements present themselves differently, and whether they act as a mechanism of discrimination rather than a simple matter of difference,” she says.

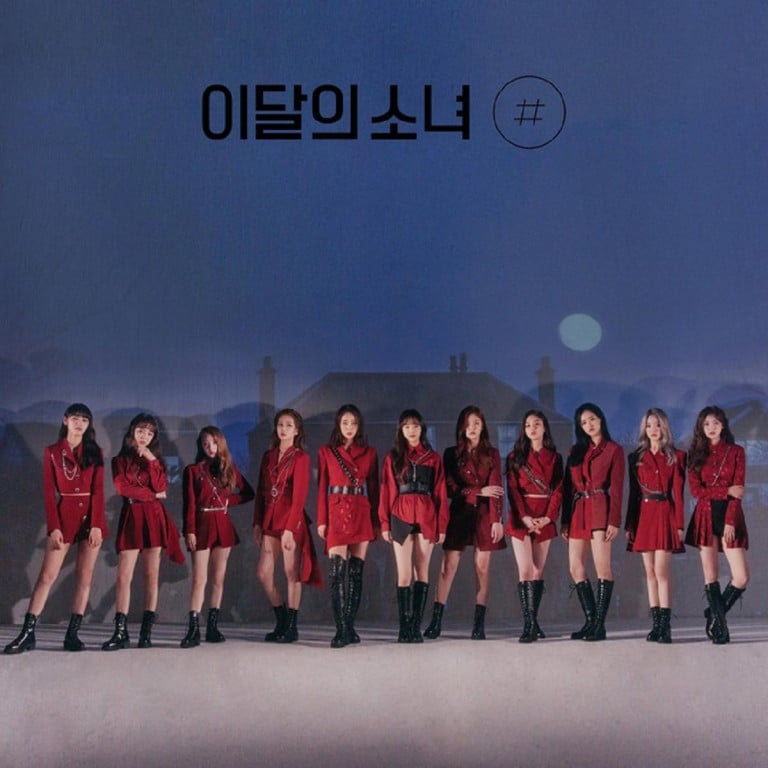

The most typical and deep-seated problem is the sexual objectification of girl group members in music videos and performance clips.

In those videos, each part of a woman’s body – from her legs and breasts to lips and hips – often appear separated from their whole, highlighted at a granular level and consumed independently of the woman they belong to. The music videos of Park Jin-young’s Who’s Your Mama? and Orange Caramel’s Catallena are some examples that take the male gaze’s objectification to the extreme, according to the book.

But female idols are constantly objectified even beyond sexually charged contexts, with the most representative images being those of a young schoolgirl, elf or goddess. These three labels have been visually associated with traditional Korean feminine ideals of purity, naivety and harmlessness.

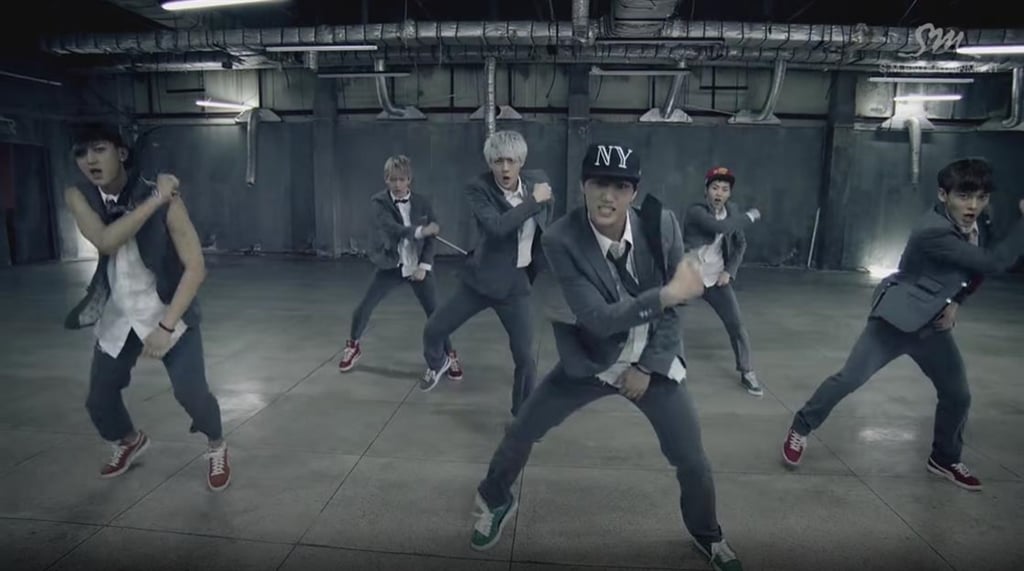

Girl groups promote the image of innocence and youth often by wearing school uniforms as stage outfits. Whereas boy bands like Exo and BTS might use uniforms to re-enact angsty teenagers’ spirit of defiance and highlight their power and adulthood through casually worn shirts and ties, female idols are portrayed in a highly romanticised, nostalgic setting that focuses on their everyday activities and love life at school, the book explains.

“While boy bands’ uniforms can serve as a tool to criticise society and its system, girl groups’ uniforms are usually limited to being a metaphor for distant memories of puppy love and bygone innocence,” Choi writes.