Beijing’s Forbidden City is 600 years old – 5 mind-blowing facts about the Chinese imperial palace brought to life in Qing dynasty period dramas like Story of Yanxi Palace

Beijing’s Forbidden City turns 600 years old in 2020, while the public Palace Museum opened to visitors 95 years ago – here are some fun facts about the Unesco World Heritage Site that was saved from the ravages of Mao’s Cultural Revolution

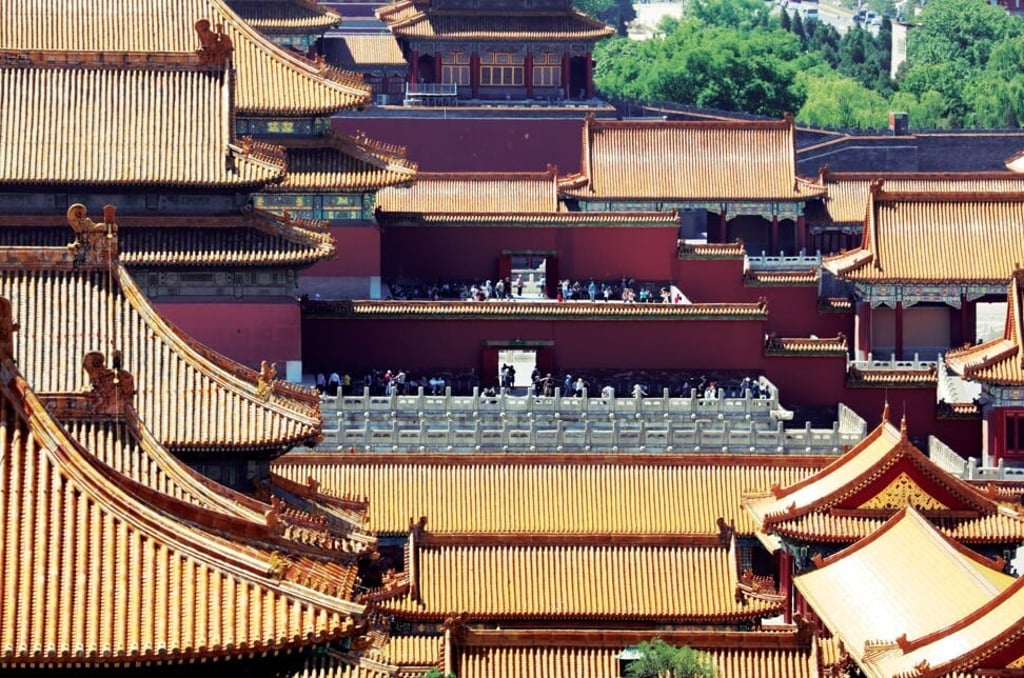

Under the watchful gaze of Mao Zedong’s portrait, hundreds of tourists hold up selfie sticks, snapping pictures as they queue to pass through The Gate of Heavenly Peace, aka Tiananmen, the imposing front entrance of Beijing’s imperial palace.

No one could have imagined this scene in the early 20th century when the palace, now a national museum, was still home to the emperor. The vast complex served as the Chinese royal residence for more than five centuries. And as the name Forbidden City implies, commoners were not allowed to enter or even dare to glance at what lay behind those high crimson walls.

According to data released by the Palace Museum, which is housed within the Forbidden City, the complex received 19 million visitors in 2019, making it one of the busiest museums in the world.

With construction completed in 1420, the Forbidden City turns 600 this year, which also marks the 95th anniversary of the opening of the Palace Museum, established a year after the final emperor, Puyi, was finally kicked out (12 years after the fall of the Qing dynasty).

We mark the occasion by taking a closer look at the imperial palace complex and weighing up some mind-blowing facts.

How many rooms does the palace hold?

The Forbidden City is the familiar backdrop of numerous TV series set in the Qing dynasty (1636-1912), most notably hit Mandarin-language dramas Empresses in the Palace, Story of Yanxi Palace, and the latter’s Netflix spin-off/sequel, Yanxi Palace: Princess Adventure. But, in fact, construction began in 1406 during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), under the reign of Emperor Yongle, and took 14 years to complete. Since then, 24 emperors took the throne over the course of the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Lying along the central axis of Beijing, the Forbidden City covers 7.75 million sq ft (720,000 square metres) and consists of 980 buildings with more than 9,000 rooms. It is home to the largest collection of preserved ancient wooden structures in the world, and was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1987.

How was the huge 200-tonne marble dragon slab transported to the palace 600 years ago?