Is China changing its LGBT views? Tmall campaigns and Weibo posts give us a hint

China has a long track record of repressing LGBTQ+ discourse, and with it, fashion brands’ opportunities to address them in their campaigns. However, at the start of 2020, sparks of hopes ignited across different aspects of Chinese society, sending a positive signal for a more progressive future. On December 20, 2019, for the first time in China’s modern history, a government law official spoke about having received a large number of petitions to include “legalisation of same-sex marriage” into the Civil Code during a press conference.

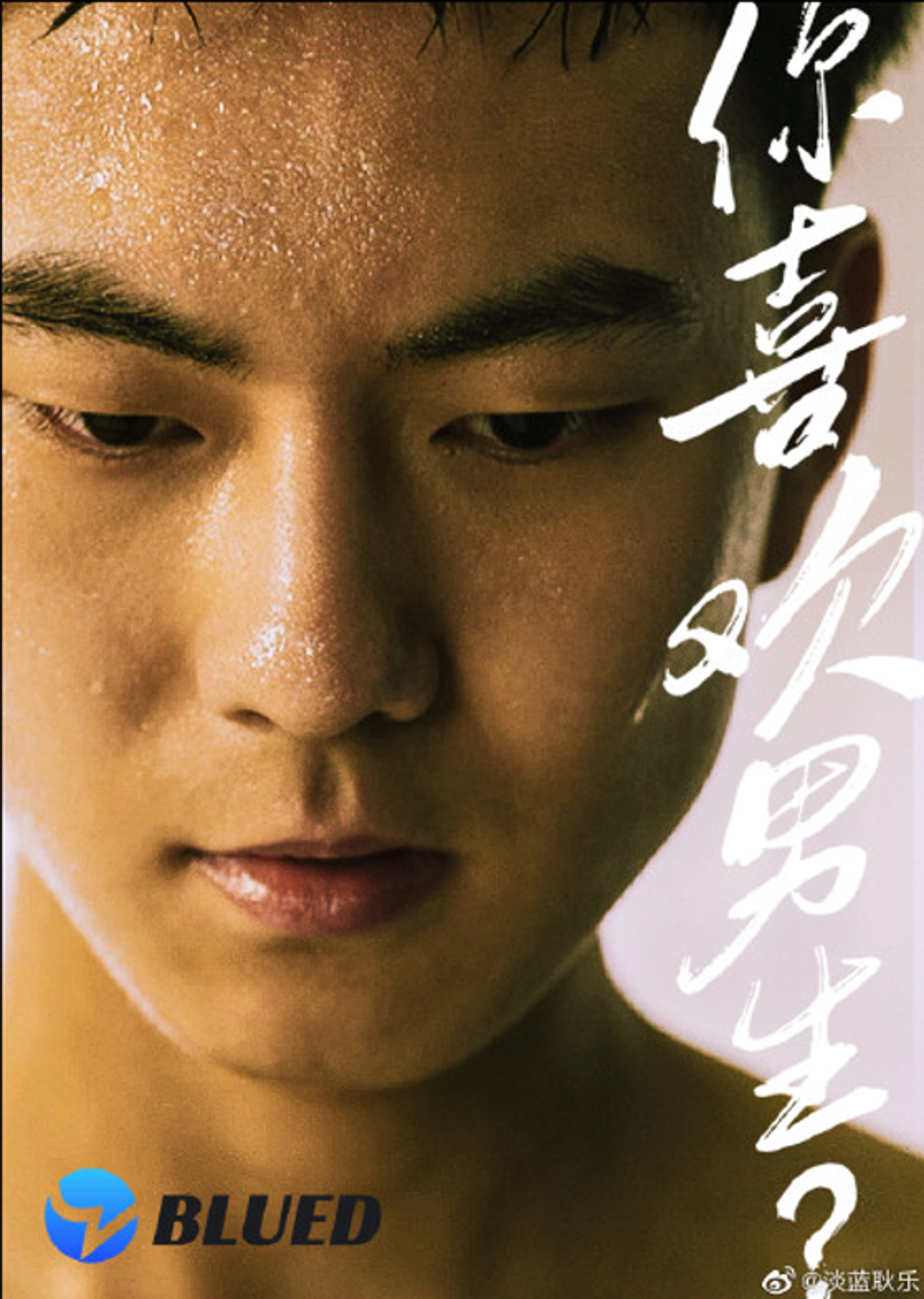

Then, on January 8, a Lunar New Year-themed campaign from Alibaba’s Tmall emerged as a top-trending search across social media. The campaign portrayed a gay couple joining a family reunion. At first, they are greeted with shock from the older parents but are eventually warmly accepted at the dinner table. The campaign received a site-wide applause on the microblogging site Weibo, as it was rare for a major company such as Alibaba to normalise a same-sex couple in a family context. In the same month, another campaign from the gay social app Blued (a local version of Grindr) aired on the internet, drawing more than 45.7 million views on Weibo. The increasing visibility of LGBTQ+ topics at the start of 2020 posed a sharp contrast to the country’s rigid silence of them during the past decades.

STYLE LGBTQ+ Series: Queer voices

Though these advertisements might seem like mild moves to the West, they signal a bold move for China given the historical contexts. China decriminalised homosexuality in 1997 and stopped classifying homosexuality as a “psychopathic disorder” in 2001. Though same-sex marriage is still far from sight, the rising volume of LGBTQ+ topics in public discourse is an encouraging sign.

It’s hard for fashion players to ignore the potential of LGBTQ+ marketing in China. After all, embracing individual expression is part of fashion’s DNA. Modern sexuality manifests itself across the industry’s products and marketing in such a profound way that it’d be untrue to take that out of a brand’s Chinese narrative. More importantly, China is home to a more than 90 million LGBTQ+ population, making it the world’s largest LGBTQ+ community. As of 2017, the annual purchasing power of this group amounted to US$938 billion. This figure does not include the vast number of straight progressives who would support brands that champion this cause.

Young, cash-rich Chinese consumers, who have contributed much to China’s luxury and fashion’s growth in recent years, are more than ready to receive progressive messages. Contrary to their state’s conservative stance, the vast majority of Chinese millennials and Gen Z are champions for shifting gender norms and modern relationships. Genderless dressing was the dominant theme at the most recent Shanghai Fashion Week and continues to gain momentum in China’s youth fashion. On the e-commerce site Taobao, businesses that cater to help LGBTQ+ couples marry abroad have mushroomed. The progressive youth has also taken this activism online. In April 2018, when Weibo started a gay content crack down as part of an initiative to clear lowbrow content, millions of young netizens boycotted the site so aggressively that Weibo had to withdraw the decision in three days.

6 LGBT hookups, break-ups and scandals that shocked Taiwan’s showbiz scene

Today, it’s both rightful and lucrative to talk LGBTQ+ in China, but it does take tactics.

1. Be bold with ideas, careful with posting

@Syl排排, a lesbian influencer with 82,000+ followers on the lifestyle platform Little Red Book, told Jing Daily that blunt wording would lead to a dead end. She said: “The description of a same-sex relationship [should] never be too blunt. For example, it’s better to use the word ‘friendship’ to describe a relationship between two women. Direct words like gay, coming out, lesbian and so on are very easy to be spotted, especially when you have a certain size of following.”

Raymond Phang, the co-founder of Shanghai Pride, also adopts “soft wording” to avoid censorship. “When posing about the Shanghai Pride Festival on various social media channels, over the years we use terms that are ‘adopted clichés’, such as ‘comrades 同志’ for ‘gay同性,’ and ‘movement运动’ for ‘promotion倡导,’” Phang said.

The same level of scrutiny goes for images. “Showing images of intimacy is risky. While most social platforms do allow kissing photos between a man a woman, intimate photos between same-sex couples risk being censored or blurred,” said @Syl排排.

2. Know your ideological battle (it isn’t religion)

In China, the biggest ideology challenge facing LGBTQ+ population isn’t about religion. It is traditional family norms, driven by the fear that homosexual couples can’t give birth to children. As a Chinese proverb goes: “There are three ways to be unfilial: the worst is not to produce offspring.” Under this belief, not having children or having a parent-approved partner makes LGBTQ+ population suffer harsh moral judgement from their own family.

Why did Ray Yeung direct the new LGBT movie Suk Suk?

According to @Syl排排, homosexual couples challenge China’s deeply entrenched family beliefs in so many ways. “Most LGBTQ+ people don’t live with their parents, which breaks the tradition of big families all living together. Some parents put a lot of pressure on men to reproduce for the family, which makes the lives of gay men especially hard,” she added.

Zeyi Yang (杨泽毅), an NYC-based journalist who covered China’s LGBT+ issues, said this population faces different struggles than in other societies. “In Western or Islamic states, LGBTQ+ people might face religious judgements from society as a whole. But in China, this population faces judgements from individual families. It’s about gaining acceptance from their own family,” Yang said. This emphasis on family acceptance was also the recurring theme of the two same-sex couple campaigns by Tmall and Blued.

3. Work on your angle

In China, homosexuality cannot be promoted or encouraged. But universal values such as inclusion, modern gender norms, diversity and cultural progress are widely accepted. It allows room for brands to address the issue without getting shunned.

“To avoid being misinterpreted as promoting homosexuality, some gay rights associations in China geared their communication towards resolving family conflicts. This makes them gain credits for building family harmony,” said journalist Zeyi Yang. Workplace inclusion is another angle to consider. On March 6, Bytedance, TikTok’s parent company, became the first major Chinese firm to call for “more inclusivity in our workplace” in an open letter to its employees, without mentioning a word of homosexuality. Similarly, brands would need to be nimble and agile to go along China’s censorship scheme.

Navigating China’s ambiguity towards LGBTQ+ issues will not be easy for international brands. But fashion, with its discretionary and progressive nature, has always been the agents of change. The industry is a vehicle for fantasies but also cultural progress. And now is the right time to talk to this long-ignored audience.

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter .

China has world’s largest LGBTQ+ community, and rich Chinese who spend on luxury fashion brands are more than happy see advertising reflecting positive images of those citizens