Exhibition sheds light on origins of modern Korean art

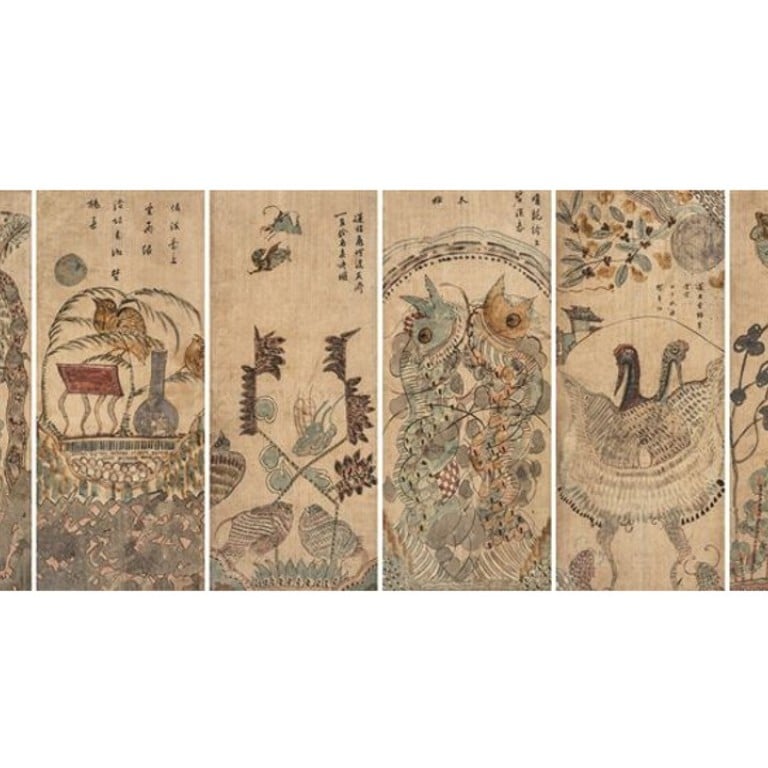

Flowers and birds are the main subjects of minhwa, or folk paintings from the 19th century

An exhibition at Gallery Hyundai sheds light on the flower paintings from last century of the Joseon Kingdom (1392-1910) as the origin of Korean modern art.

Flowers and birds were the most popular subjects of “minhwa” (Korean folk painting) in the 19th century as they symbolised wealth, honour and marital harmony. Despite their artistic value, these paintings were considered to have originated from the lower class and hardly researched.

Do Hyung-teh, CEO of Gallery Hyundai, said he found the answer to one of the most frequent questions when he promoted Korean art overseas – what is the root of Korean abstract art – from the flower and animal paintings.

Many modern Korean artists, including Lee U-fan, Chang Uc-chin, Kim Chong-hak and Kim Gi-chang, loved minhwa and collected these flower paintings and this hints at the influence of Korean minhwa on modern Korean painting, especially abstract art.

Gallery Hyundai will display minhwa, antique furniture pieces and Korean porcelain with modern Korean abstract paintings during the Frieze Masters art fair in London in October.

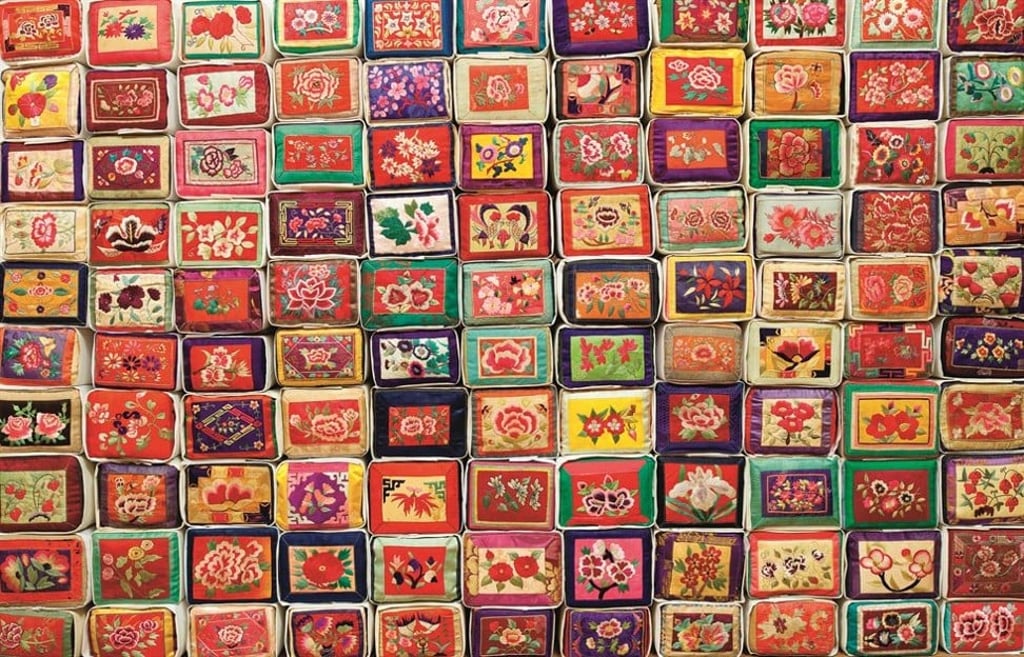

Titled “Flower Paintings from the Joseon Dynasty”, the exhibition features flower paintings mainly from the 19th century. The exhibit is held at three venues of Gallery Hyundai – Flowers and Small Animal paintings in the Main Space, Peony and other Flower paintings in the New Space and works of embroidery in the Dugahun Gallery.

Though the Korean title of the exhibit indicates these paintings are minhwa, often translated as folk art, Professor Kho Youen-hee of Sungkyunkwan University, who co-curated the exhibition, pointed out that the paintings originated from the court and were popular among “yangban” or noblemen, during Joseon Kingdom, differentiating them from other folk paintings.

“Most of the existing flower paintings were created by court painters or aristocrats. Though they are called ‘folk painting’, few of them were actually made by ordinary people,” Kho said. “But such an art-loving culture was passed down from above and each Korean household had paintings of flowers and books of the past. Many of the artworks, though, were destroyed during the Korean war (1950-53) and taken away during the Saemaul Undong in the 1970s because they were considered old and outdated.”

Kho said most of the paintings on view, borrowed from private collectors such as the late renowned painter Kim Gi-chang and private museums including the OCI Museum of Art and Onyang Folk Museum, are likely to have originally been displayed at homes of high ranking officials or even the palace.