Lure of the greasepaint: why academic chose life in spotlight as a Cantonese opera star

- Sam Chan Chak-lui knew what she wanted to do as a career when she was still a child and so began making plans to achieve it when she was only 10.

- Later she turned her back on her job as a university lecturer for a life on the stage – as a Cantonese opera artist, specialising in playing male protagonists.

“I wanted to work at the university so that I could earn a steady income to pay for my passion,” says Chan, 42, who began training her voice and improving her physical agility in order to perform Cantonese opera at the age of 10 – without her parents’ knowledge.

She was forced to borrow funds from a cousin to ensure what she was doing remained a secret – in the certain knowledge that, should her parents find out, they would disapprove of what she was doing.

“They wanted me to study something more academic,” says the former lecturer who has spent the entire academic career at Chinese University of Hong Kong from her bachelor studies. “And so I did, but my heart was still with opera.”

At this year’s 47th Hong Kong Arts Festival, Chan will perform in the legendary Tong Tik-sang’s Red Cherries and a Broken Heart, a classic story of self-reliance that flourished overseas among Chinese migrants in the early 20th century, on March 9, and the following day, in a series of vignettes from Pak Yuk-tong’s Three Big Trials, centred around legal justice.

Chan typically performs on Hong Kong stages more than 20 times a month – either at Yau Ma Tei Theatre, Ko Shan Theatre or Xiqu Centre, the US$346 million multi-theatre West Kowloon complex, which is the modern home for Chinese opera in the city.

The week leading up to a performance at Yau Ma Tei Theatre sees Chan spends her Monday morning with three hours of rehearsing by herself.

Performing in an empty theatre allows her to grow comfortable as her role while standing under the fluorescent lights. Chan spends about 30 minutes doing stretching to warm up her muscles and her voice before she starts.

The halls’ heavy black stage curtains help to dampen occasional sounds made by maintenance workers or security guards so that the room takes on an absorbing silence, which allows Chan to focus on practising her exacting movements and generating the precise pitch of her voice.

For more than 10 years, Chan lectured full-time in cultural and religious studies. Then in 2016, she gave up her stable lifestyle for Cantonese opera.

“There had been years in my life when I was completely separated from the arts,” Chan says. “At those times I felt I had no purpose in life.” With no one to distract her or pass judgment on her rehearsal, it is up to Chan to decide if the minutiae of her movements are too subtle, too dramatic or just right.

Her water sleeves – long silk cuffs on the traditional Cantonese opera garment Chan is wearing – accentuate her myriad hand movements as she practises – coaxing the fabric into folding and unfolding with little visible effort.

The movements of Chan’s slender figure mirror the essence of the sung and spoken acting role. “Every actor has to be very aware of how to adapt their physique and body shape to the part they are playing,” says Chan, whose near-1.83-metre (6-foot) frame gives her a distinct advantage when playing male characters — sometimes a scholar and sometimes a warrior.

Instructors typically choose a path for their apprentices early on, based on their strengths. Chan, who has a doctorate in gender studies, says she regards gender as a societal role, separate from sex – not unlike the roles that actors play onstage.

Despite her demanding training schedule, Chan makes an effort to take a break after the morning’s solo rehearsal and have lunch – of pasta and coffee – with some of her Cantonese opera friends in a Jordan cafe, near the Xiqu Centre.

The three friends speak about their characters, the movement and design of their plays and performing at Xiqu Centre. Chan says these friends and colleagues are of paramount importance in her being able to cope with any problems that arise behind the scenes and when on stage.

“I am very stubborn and get frustrated at times,” Chan says. “They help me to stay positive and flexible in difficult environments.”

On Tuesday morning Chan meets Zheng Fukang, who has been her martial arts teacher for nearly 12 years, in a practice room at the Ko Shan Theatre in Hung Hom.

The first 30 minutes of their two-hour session involves Chan carrying out highly physical drills, after which she is left breathing hard, with beads of sweat visible on her brow – and another 90 minutes still to go.

Zheng, who is a seasoned martial arts choreographer, started his career in Peking opera. Aside from coaching operatic performers, he has taught many film actors how to realistically perform kung fu in fight scenes.

His gentleness and expertise is met with the utmost respect; Chan refers to Zheng only as “teacher” – a role that she reveres and hopes to take on in the future.

“It is my responsibility to pass on this art form,” she says. “It’s now or never. Most of the masters are septuagenarians and there will be no more masters like them from whom I can learn.”

Cantonese opera is undoubtedly a labour of love for Chan and her fellow performers. There are four areas where every actor must hone their craft: singing, acting, reciting and acrobatic fighting.

Her dedication is obvious because of the audible whooshing sound she makes as she twirls her training sword through the air. Zheng says that Chan’s decision to focus on Cantonese opera full time was necessary in order for her to master her roles because the routines grow increasingly challenging. He then recites an old Chinese saying: “When you spend one minute on the stage, you spend 10 years to practice it.”

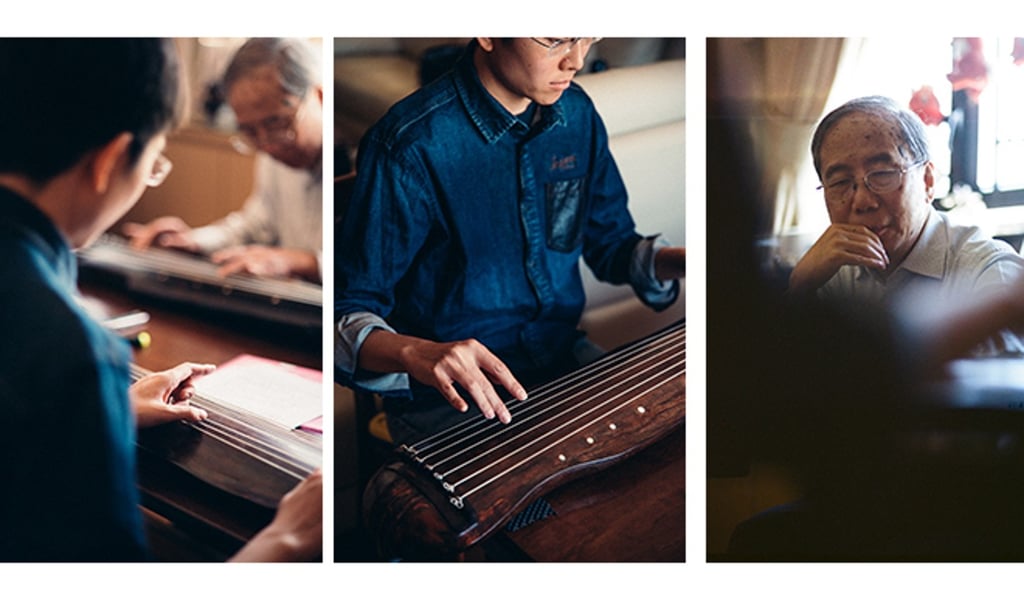

After a hasty lunch at the theatre, Chan goes directly to her next lesson, where the soft sounds of the guqin – a plucked seven-string Chinese musical instrument from the zither family – help to ease the anxieties that arise from her chosen career.

Speaking of the hardships she endured during her time away from the opera, Chan says she easily becomes emotional and agitated. She regards playing the guqin as an antidote to the stresses of Hong Kong life – and the loud, extroverted nature of operatic performance.

The strings of the traditional instrument, sometimes known as ‘the instrument of the sages’, are tuned in the bass register, in contrast with the high octaves of Cantonese opera.

“Playing the guqin is calming and quiet,” Chan says. “It makes me feel as if I am not [living] in a city.”

Tse Chun-yan, a retired doctor, who now has a second career as one of a handful of guqin masters in the region, has been teaching Chan to play the instrument for a decade.They practice together each week in the comfort of his family home, which is full of the signs of a long life well lived as a parent, grandfather – and musician.

“It is a long-term relationship,” says Chan, who also refers to Tse simply as “teacher” – the same term of unwavering respect and attentiveness she adopts with all the mentors in her life.

The force and attenuation of Chan’s fingers on the guqin’s strings resemble the same seamless alternation between grace and formality her hands display when performing Cantonese opera on stage.

With both of these once-beloved bastions of Chinese culture now threatened by non-succession, Chan regards her lessons as a form of cultural inheritance that must be approached with the utmost care.

On Friday, the day of her performance, Chan arrives backstage at the Yau Ma Tei Theatre nearly four hours before the three-hour show begins.

Other actors arrive as Chan is beginning to apply the third layer of her foundation: a bright shade of magenta surrounds her eyes, dramatising her expression. An acquired skill, Chan has been applying her own make-up backstage for more than 20 years.

In Cantonese opera make-up is indicative of the nature of each character: arrowlike shading between the eyebrows suggests a character is hot-tempered, whereas circular shading signals someone playing a more humorous role.

Chan has finished her simple dinner in her dressing station in silence long before the others have arrived. “I do not want to talk to anyone,” Chan, who will play one of two main characters, says. “I need to focus and think only of the role and keep all of my lines in my head.”

Deep in thought as she drinks tea from a porcelain teapot spout, to avoid smudging the lipstick on her meticulously painted lips, Chan’s backstage movements are deliberately slow and restrained to avoid any distraction.

After she finishes applying her make-up, she goes back to carefully studying her lengthy script, filled with handwritten notes and pink marks from a highlighter pen.

After an hour spent of putting on her make-up and layers of costumes, Chan is unrecognisable. She has successfully transformed herself into her character – a young man who has been separated from his wife, but has found her anew – and now, with the metamorphosis complete, Chan and her fellow actors take on the roles of their characters on stage.

Chan says the feeling of exhilaration generated from performing stay with her long after she has left the stage. “It is amazing to share my thoughts, feelings and the creation of the characters with other performers and the audience during the show,” she says.

“We can feel a real connection between us – it’s as if there is energy flowing around the theatre.”

Editor’s note:

In the lead up to the month-long Hong Kong Arts Festival from 21 February, there’s plenty to offer in addition to Chinese opera -- from jazz concert to musical and ballet show. Find out more on the programs and get your tickets on Hong Kong Arts Festival website.