Summits and good vibes for Xi, Trump, Moon and Kim, but why is Japan still so wary of North Korea detente?

Shinzo Abe wants to chime in on the high-stakes diplomacy, but his concerns are the same as others’ and the US has again taken the lead for its key Asian ally

Asia’s most powerful players Xi Jinping, Donald Trump and Moon Jae-in have been jostling for poll position in the high-stakes negotiations with North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un. By the end of the month, all three leaders – and even some of their subordinates – would have sat face-to-face with the young dictator at least once.

But with so many meetings popping up, one cannot help but wonder where Shinzo Abe has been and what the Japanese are feeling?

Kim has met China’s President Xi twice in recent weeks and had a historic summit with South Korean leader Moon last month. He met US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo for the second time on Wednesday and is poised to sit down with Trump in the coming weeks.

But Japan’s Prime Minister Abe – a treasured ally of the US – has been cast to the sidelines despite repeated calls to be included and his country being one of the closest neighbours to the nuclear-armed North.

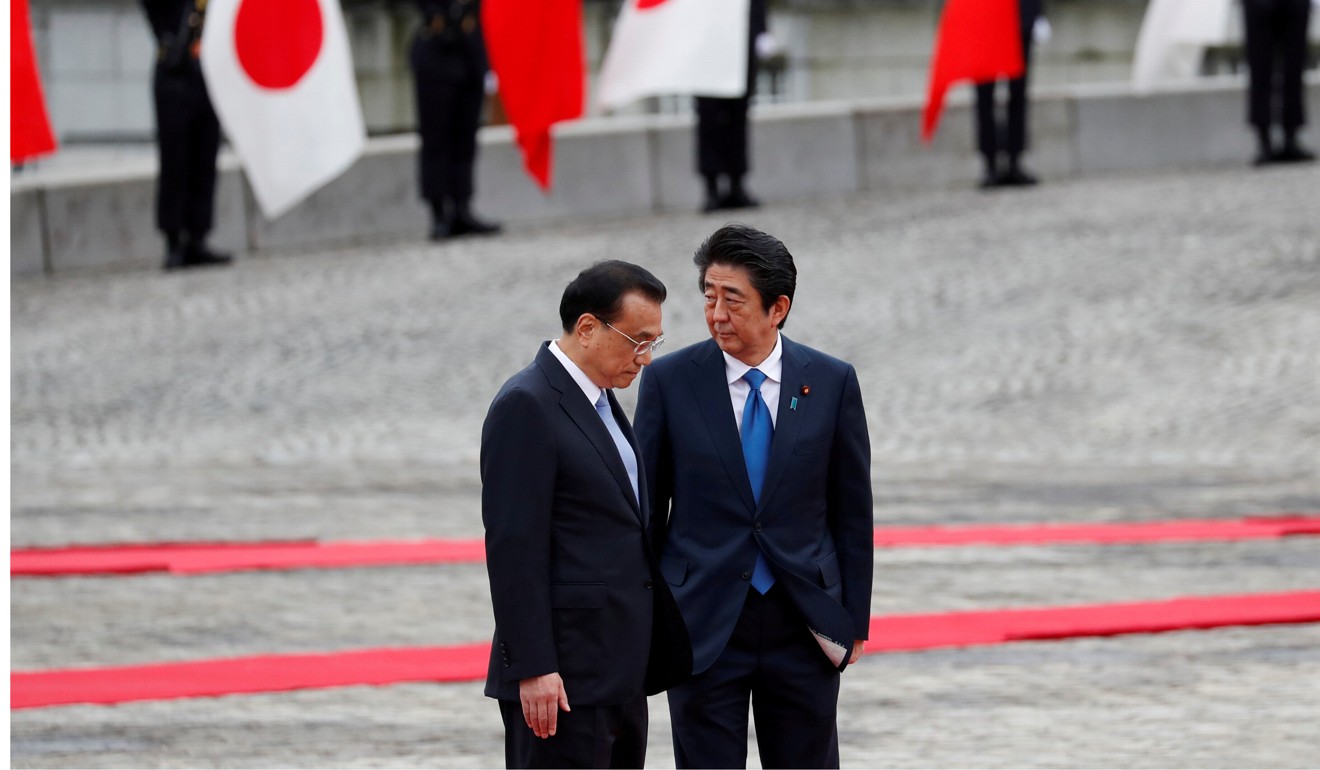

Domestically some media have suggested Wednesday’s trilateral summit in Tokyo between Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, Abe and Moon was hastily arranged to demonstrate Japan’s relevance in the Korean Peninsula situation. And Abe has not been shy about charming his way into further cooperation.

On Wednesday, he praised Moon and China’s efforts to engage North Korea. And after his working lunch with the South’s leader, Abe presented Moon with a cake to mark his first anniversary since taking office.

“We must take the recent momentum towards denuclearisation on the Korean peninsula and towards peace and security in Northeast Asia, and, cooperating even further with international society, make sure this is linked to concrete action by North Korea,” Abe said after the meeting.

Watch: China wants to stay relevant in Korean Peninsula affairs

Abe is a staunch supporter of keeping maximum pressure on Pyongyang and opposes “rewards” for the regime until there is clear evidence of it scrapping its nuclear arsenal and programme. He is a reluctant supporter of engaging with Pyongyang, largely because he believes it will not lead to the return of 17 Japanese citizens who, the government says, were abducted by North Korean agents between 1977 and 1983 to train future generations of its spies.

Jun Okumura, a political analyst at the Meiji Institute for Global Affairs, said Abe built his early political base on the issue of the abductees and will not abandon his convictions, but he must balance that with other matters of similarly pressing urgency.

“I am certain the abductions will be on the agenda and in the final communique, but I expect that will be largely for show and that the South Koreans and Chinese will be willing to accommodate that position as long as it does not jeopardise the bigger picture,” he said.

Japan is also calling for the elimination of the North’s arsenal of ballistic missiles, including shorter range weapons capable of striking targets in Japan, and its stockpiles of chemical and biological weapons. And Moon Jae-in, the South Korean president, will have sympathy with that position, Okumura said.

Stephen Nagy, an associate professor of international relations at Tokyo’s International Christian University, agreed that while the narrative in the domestic media has been that Japan has been bypassed in diplomatic developments, that is not the case.

“Tokyo may not have been front and centre in discussions, but when you look at all of Japan’s concerns it is clear that they have been gradually worked into Washington’s position in the last few weeks.”

“The abductions are on the agenda, so are short-range missiles, chemical and biological

weapons and so on. So once again, we see the US acting effectively as Japan’s proxy because they have the political, economic and military capital to do that.”

Yet there is far less belief in Japan that discussions between Pyongyang and the rest of the international community will pan out as well as the optimists anticipate.

The sense is that North Korea is playing its diplomatic hand masterfully and it will ultimately decline to scrap its nuclear arsenal. With that, the North will recover the support of a Chinese government and, sooner or later, the region will return to a hostile stalemate across the demilitarised zone with a better armed Pyongyang.

While Okumura said there is a definite scepticism among Japanese people that this ongoing bout of feel-good diplomacy will develop into detente, friendship and even reunification, Nagy went further. He said Japan has reason to fear two of the possible scenarios.

Nagy said the likely scenarios are the North Koreans getting caught concealing nuclear weapons capabilities and a sudden return to hostility on the border, albeit with Pyongyang better armed because it has bought itself more time and is potentially closely aligned with China again. President Donald Trump may also decide to wash America’s hands of the region.

That, in turn, would permit China to seize the initiative as a virtually unchecked power and either encourage or coerce both North and South into its sphere to create an additional military and economic counterweight to rival Japan.

“For Japan, the best outcome would be a confederation on the Korean Peninsula that would see Seoul remaining pro-US and Pyongyang close to China, but with nuclear weapons removed from both sides,” Nagy said.

“That, for Japan, would be tolerable.”