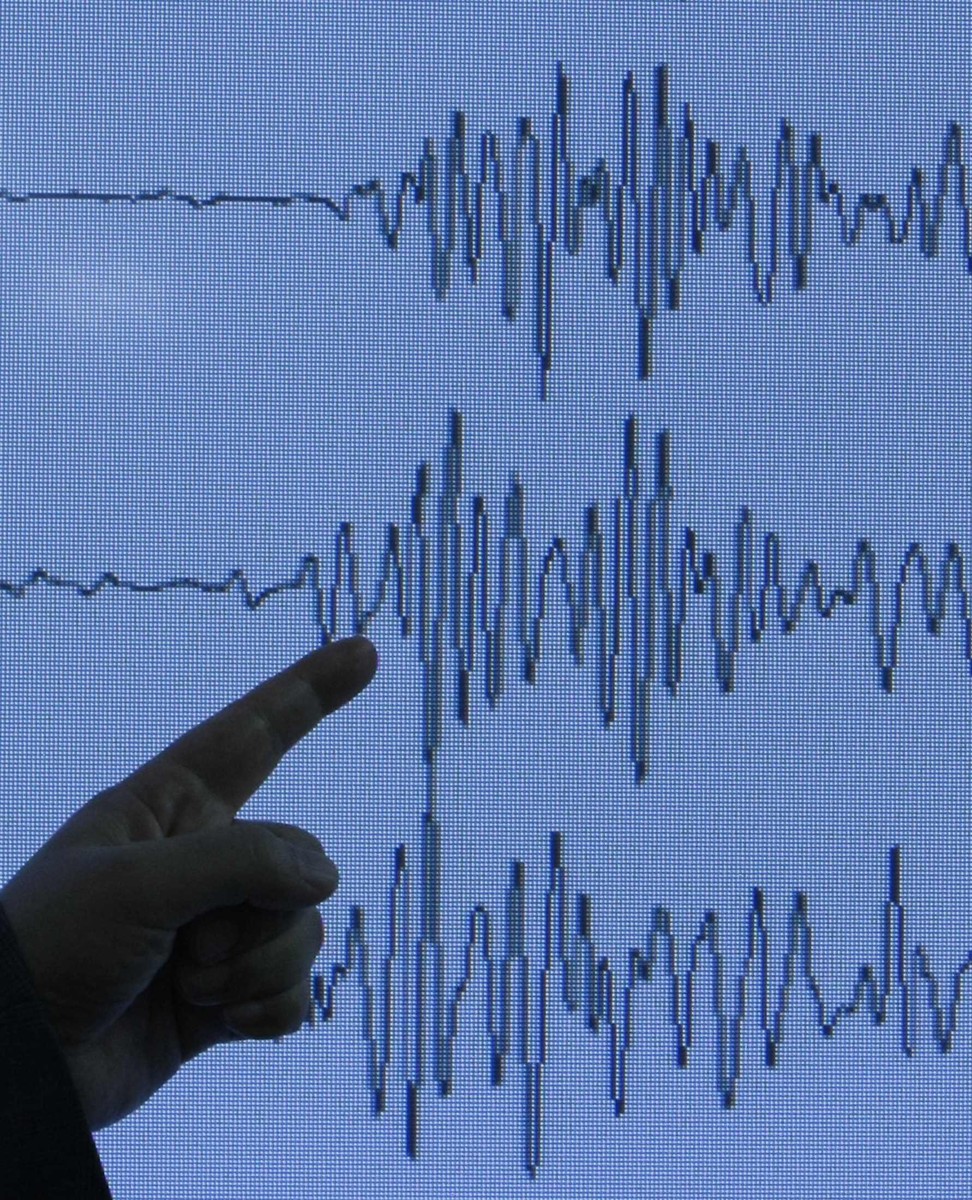

How prepared is Tokyo for giant earthquake that could kill 10,000 people and destroy 300,000 buildings?

- Experts say there is a 70 per cent chance of a magnitude-7 quake hitting Tokyo before 2050. It is no longer a question of if – but when – the big one will come

- A magnitude-7.3 quake striking northern Tokyo Bay could kill 9,700 people and injure almost 150,000, with an expected peak of 3.39 million evacuees the next day

Every day, at 5pm, the gentle melody of the children’s song Yuyake Koyake chimes across the Minato area of Tokyo from a loudspeaker – one of hundreds dotted across schools and parks throughout this megacity of 37 million people.

The last great quake to hit Tokyo was in 1923. Experts estimate the next one is due roughly a century on, with an estimated 70 per cent chance of a magnitude-7 quake hitting Tokyo before 2050. It is no longer a question of if – but when – the big one will come.

The impact would be devastating. According to an official estimate, a magnitude-7.3 quake striking northern Tokyo Bay could kill 9,700 people and injure almost 150,000. There would be an expected peak of 3.39 million evacuees the day after the disaster, with a further 5.2 million stranded, while more than 300,000 buildings could be destroyed by the earthquake itself or the ensuing fires.

It would be the most calamitous event to confront Tokyo since the US firebombing of March 1945 that killed 100,000 people and burned down more than 267,000 buildings.

When the magnitude-7.9 Great Kanto earthquake struck beneath Oshima Island, about 100km south of central Tokyo, around lunchtime on September 1, 1923, thousands of buildings collapsed. Fires broke out in homes as cooking stoves overturned, and people who escaped described the aftermath as hell on earth. The combined death and injury toll was officially estimated at 105,000 across Tokyo and the adjacent port city of Yokohama, although some reports said it was far higher.

In the chaotic aftermath of the disaster, false rumours about a “Korean revolt” and the alleged poisoning of wells also triggered outbreaks of deadly mob violence against Koreans.

Tokyo has come a long way since 1923. If any city is prepared for an earthquake, it is this one. The hi-tech skyscrapers are designed to sway, the parks feature hidden emergency toilets and benches that turn into cooking stoves, and the city has the world’s largest fire brigade, specifically trained to prevent the kind of flash blazes that spread after earthquakes.

“Japan is world famous for its resilient infrastructure and for its seismic technologies. If you look around the Tokyo skyscrapers it’s incredible how advanced a lot of technology here is, especially seismic resistance – but my concern is preparedness at the community and individual level,” says Robin Takashi Lewis, a Tokyo-based specialist in disaster preparedness and response.

“In the event of a big earthquake here … there would be significant damage to critical infrastructure such as electricity, gas, water,” Lewis says. After a major quake, the Tokyo metropolitan government says it aims to restore power within a week, water supply in a month and gas within two months.

Tokyo planners unfazed by quake threat to Olympics 2020

“When you have a city this big and your basic lifelines are out, that’s a very significant problem.”

Yes, Tokyo has the largest urban firefighting force in the world. “But in the case of the ‘big one’, the Tokyo inland earthquake, the emergency services would be overwhelmed.”

Tokyo householders are urged to secure furniture to the wall using L-shaped brackets, and place wedges under unstable cabinets and anti-slip pads to chair and table legs. Tokyoites are also advised to always store extra canned food and bottled water, as well emergency kits with flashlights, a radio, batteries and everyday medications. Shops sell “emergency toilet bags” that can be attached to a standard household toilet when the water supply is cut off. They are well-drilled to take shelter under tables or to hold cushions or pillows over their heads, to ward off falling objects.

Don’t worry. 634m Tokyo Skytree is earthquake proof. Maybe

Millions of people, however, could be travelling on Tokyo’s railway and subway network when the quake hits. The Tokyo Metro says its infrastructure has been seismically reinforced, and that trains will make an immediate emergency stop in strong shaking; it advises passengers to hold tightly to handrails and straps.

Naoshi Hirata, a professor of seismology at the University of Tokyo’s Earthquake Research Institute, says the city is at particular risk because two oceanic plates are pushing up against the area – and because Tokyo lies on the flat Kanto Plain, a geological formation that is easily shaken.

The Japanese are used to the concept of natural disasters. Schools and companies commonly hold emergency drills on September 1, the anniversary of the 1923 quake now known as Disaster Prevention Day. The Tokyo metropolitan government has published a 338-page manual, “Let’s Get Prepared”, outlining what people should expect from various disasters, and how to reduce their risk.

In the case of the ‘big one’, the Tokyo inland earthquake, the emergency services would be overwhelmed

Distributed to 7 million households and produced in multiple languages, it includes a short manga comic strip called Tokyo ‘X’ Day, starring an office worker navigating scenes of destruction: falling objects, derailed trains, crashed vehicles, damaged buildings and mobile network outages. The story concludes with the words: “This is not a ‘what if’ story. In the near future, this story is sure to become reality.”

The city is also working to update and improve its infrastructure. Although its international image is one of dizzying modern skyscrapers, experts are worried about the city’s traditional fabric: pockets of close-set, wooden houses where fire could spread quickly.

Hokkaido quake reveals how unprepared Japan is to help foreigners during disasters

“We still have about 13,000 hectares of concentrated wooden houses, which is about 7 per cent of the area of Tokyo prefecture,” Nobutada Tominaga, an official from the city’s urban development bureau, told an urban resilience forum in Tokyo last month. One recently completed project involved the installation of wide pedestrian zones to help create fire breaks in the older suburb of Nakanobu.

The city also reserves a network of major roads for fire trucks and rescue vehicles. These roads are marked with the sign of a large blue catfish, the Namazu – the giant creature that causes earthquakes in Japanese mythology.

The city has chosen 3,000 schools, community centres and other public facilities to operate as evacuation centres in the event of a major disaster, and there are about 1,200 centres for people who need special care.

Faced with the prospect of 5.2 million stranded people in a major quake, the Tokyo metropolitan government wants to avoid mass movements of workers returning home and advises people to stay where they are at their workplace or school if possible.

Japan earthquake, tsunami fears heighten after oarfish sightings

Accordingly, business operators are used to keep at least three days’ worth of drinking water, food, and other necessities so that their employees have access to adequate supplies in a disaster. The government has also designated temporary shelters for those people who have nowhere to go, where similar supplies will be available.

Meanwhile, more than 50 sites across Tokyo have been designated as disaster prevention parks. In normal times, they’re used for picnics and other leisure activities, and resemble standard parks in every way except for a grid of manholes in a fenced-off area. After a disaster, the manhole covers are removed and special seats and privacy tents are placed over them, turning them into emergency toilets. The park benches, meanwhile, can be converted into cooking stoves. Emergency response would be coordinated from the Tokyo Rinkai Disaster Prevention Park, a 13.2 hectare site to the north-west of Tokyo Bay.

Why giant quakes continue to devastate poorer Asian communities

A lot will come down to the magnitude of the quake and exactly where it strikes. And no matter how prepared Tokyo thinks it might be, it is hard to formally plan for chaos. After the huge earthquake that struck modern, supposedly quake-proof Kobe in 1995, killing 6,434 people and destroying nearly 400,000 buildings – including the elevated Hanshin Expressway, which collapsed – about four in five people requiring rescue were helped by other members of the public rather than the city’s official disaster responders.

When X Day finally arrives, it may be the people of Tokyo themselves who will be called upon to save their own city.