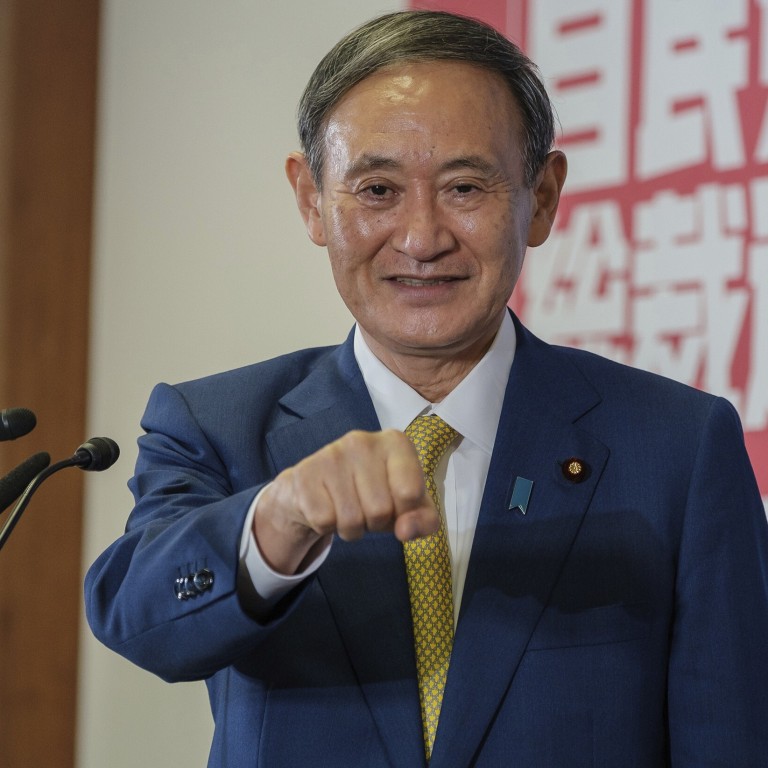

Will Yoshihide Suga break Japan’s ‘curse’ of quick turnover of prime ministers?

- Suga will replace Japan’s longest-serving PM Shinzo Abe on Wednesday, but before Abe, the country averaged a new premier about every two years

- Analysts say Suga’s ability to control the bureaucracy and a weak opposition mean he will retain LDP leadership and is likely to win the next election

“If anyone has a chance of breaking the ‘curse’ it’s Suga,” said Tobias Harris, an analyst at advisory firm Teneo Intelligence and author of a new biography of Abe. “His ability to control the bureaucracy, his relationships with the ruling coalition, and the public’s desire to avoid a return to the revolving door all suggest that he could be well positioned to win a term of his own next year and wield power for several years.”

Suga, 71, will initially serve the remaining year of Abe’s term in office, though some party members have raised the prospect he may soon call an election to get a fresh mandate while the opposition remains weak.

Can post-Abe Japan leave China’s shadow to lead Asia?

The ease of Suga’s victory is a good sign for his ability to manage the LDP factions. The party coalesced around him almost as soon as Abe announced his intent to step down over health issues in late August. Instead of a bruising fight, faction bosses opted for an election system that favoured Suga, and within two days had lined up enough support for him to win.

While Suga does not have his own formal faction, he has honed his skills as a pragmatic back room fixer during his time as Japan’s longest-serving chief cabinet secretary. His strong alliances with the likes of Toshihiro Nikai, an influential faction leader as well as LDP secretary general, underpinned his win on Monday.

In a sign of maintaining stability, Finance Minister Taro Aso, a faction boss who backed Suga, will retain his cabinet post in the new government, the Nikkei newspaper reported on Tuesday. Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi will also stay in his post when the new cabinet is announced on Wednesday, broadcaster NTV said.

Kyodo reported that Suga will retain Nikai as LDP secretary general while naming former education minister Hakubun Shimomura as policy chief. Suga also plans to appoint Tsutomu Sato, a former minister of internal affairs and communications, as chairman of the General Council while retaining Hiroshi Moriyama as head of the Diet Affairs Committee, party sources said. Seiko Noda, a female lawmaker who is unaffiliated, is expected to be appointed as the party’s executive acting secretary general.

Suga also has certain advantages over Abe’s predecessors who quickly lost public support due to policy stumbles or scandals. In the 50 years before Abe’s record run, Japan averaged a new prime minister about every two years.

For one, Suga’s blessed with an opposition that has largely failed to pose a threat in terms of voter support over the past eight years.

“I don’t think there’s a high probability of a quick turnover of prime ministers,” said Yu Uchiyama, a professor at the University of Tokyo. “The reasons why that happened before were weak standing within the party enabling powerful factions to oust a premier, or a ‘twisted parliament’ that hampered management.”

Shinzo Abe wanted Japanese women to ‘shine’. What happened?

Still, hurdles that have tripped up other leaders are in Suga’s path, including a campaign finance scandal and arrests for bribery related to opening casino resorts in Japan. Suga has not been directly implicated in any of these issues.

The new leader will also take charge of an economy that saw the biggest contraction on record in the April-June quarter while the cabinet’s handling of the pandemic has often come in for criticism.

One wild card is Suga’s skill in timing elections – a factor that helped Abe stay in power so long. In 2017, he and Abe cut off a bid for the top job by Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike by calling a snap election before her new group was prepared.

Suga said he does not think the country is in a situation to call an election now, but that could change as a second Covid-19 wave fades. Tokyo held a governor election in July.

Japan’s next PM: with Abe gone, could Suga hit China-US sweet spot?

With the LDP almost guaranteed victory whenever the vote is held, Suga could head into the 2021 party leadership election with a huge advantage as the incumbent prime minister, opening the way for another term at the top – and keeping the revolving door firmly shut.

“A long administration gives you more influence in the international community,” and Japan has learned there are merits to that from an economic point of view as well, said LDP lawmaker Shigeharu Aoyama, who sees Suga staying for at least three years.

“I don’t think we will return to the times when we had a new prime minister every year.”