Over 40 years of diplomatic drama, a rising China opens up to, and transforms, the world

- When the inner circle of China’s Communist Party endorsed a new direction for the country in December, 1978, few would have imagined the immense changes that would be unleashed. Deng Xiaoping’s push for ‘reform and opening up’ launched China’s rise from the wreckage of the Cultural Revolution to the world’s second-biggest economy

- To mark the 40th anniversary of the start of the process, the South China Morning Post takes an in-depth look at the forces that shaped that transformation. In the first part of our series, Cary Huang examines the new era of diplomacy that Deng ushered in to allow China to focus on economic development

On the blustery, cold morning of January 29, 1979, the red flag of China was flying over the South Lawn of the White House when US President Jimmy Carter welcomed Deng Xiaoping, the first Chinese leader to visit the United States since the communists took control of China in 1949.

The visit by the then vice-premier not only symbolised an end to what 74-year-old Deng described as the “period of unpleasantness between us for 30 years”, it also ushered in a new era in global geopolitics, as well as China’s development ever since.

In Washington, Deng and Carter signed accords switching the United States’ diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China in Taipei to the People’s Republic of China in Beijing.

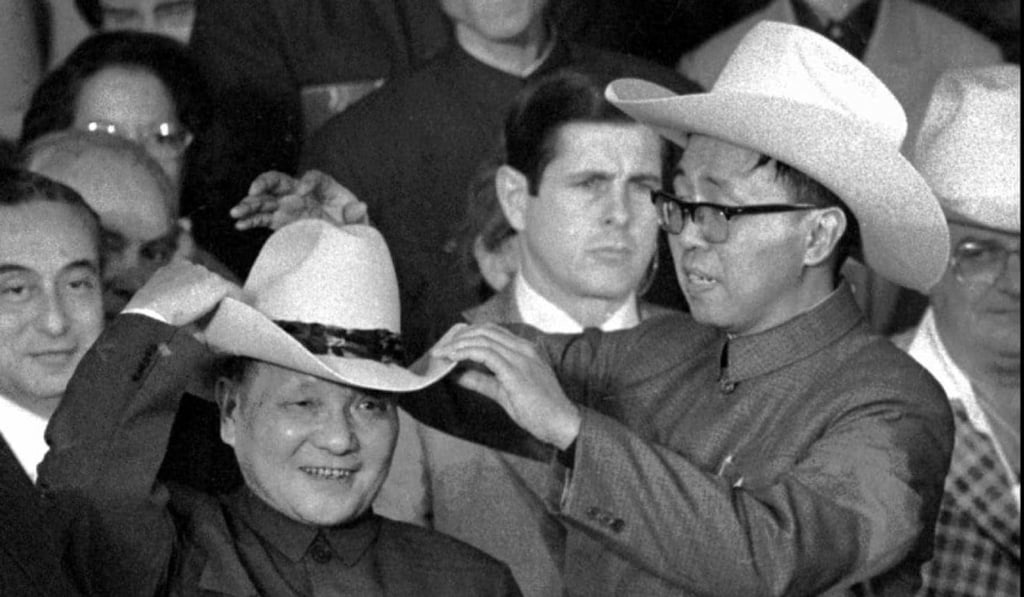

Deng was also eager to learn from the US about ways to modernise China, making stops at Coca-Cola in Atlanta, Boeing in Seattle and Nasa’s Johnson Space Centre in Texas – where during a side visit to a rodeo he captured the American public’s imagination by donning a cowboy hat.

The events both formal and spontaneous signalled an end of China’s isolation from the world, as well as Beijing’s determination to open its doors to the capitalist West.