The Sinophile driving Italy’s hopes of a New Silk Road deal with China

- Italian trade and investment tsar Michele Geraci aims to reach agreement with Beijing during Xi Jinping’s visit next week

- Italy could become the first G7 country to join the flagship Chinese strategy

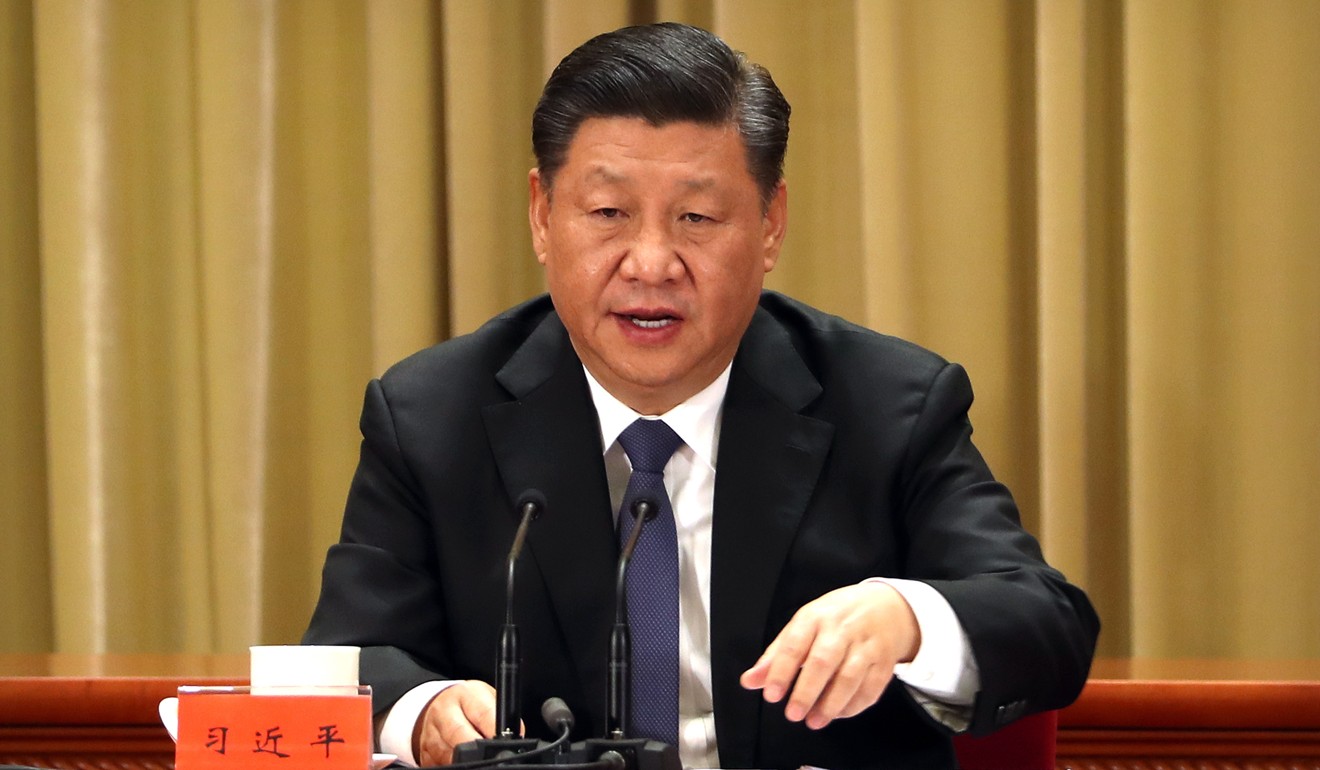

When Xi Jinping visits Italy next week, Rome’s hopes of joining China’s global trade and infrastructure plan will rest heavily on the shoulders of a powerful Sinophile who has ignored international warnings not to put too much trust in China.

Michele Geraci, the undersecretary of state for economic development in Italy’s populist coalition government, has been tasked by Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte to reach a memorandum of understanding with Beijing – for Italy to take part in the “Belt and Road Initiative” – during Xi’s March 22-24 visit.

Geraci, 53, has been helping to plan Xi’s trip, part of which will cover the Sicilian port city of Palermo, Geraci’s birthplace, the minister told Italian newspaper La Stampa last week.

“I would like to convince President Xi that it is worth investing in Sicily,” said Geraci, who speaks Chinese fluently and spent the last decade in China as a part-time professor in the eastern coastal province of Zhejiang and in neighbouring Shanghai.

An avowed Eurosceptic who opposes increasing the powers of the European Union, Geraci has also poured his China-friendly opinions into columns for Caixin, a leading Chinese financial magazine.

Geraci’s rise into a role that gives him the power to influence the euro zone’s third-biggest economy has been stunning, given his lack of political or diplomatic credentials.

In his brief tenure as the official in Italy responsible for international trade and foreign direct investment, he has proven himself possibly even more important to the cause of landing a belt and road deal than Italy’s foreign minister, having already made four official visits to China.

Noting Geraci’s value to the Conte administration, Lucrezia Poggetti, of the Germany-based think tank Mercator Institute for China Studies, wrote that the Italian government “so far lacks a balanced assessment of its cooperation with Beijing. It mainly relies on the newly appointed … Geraci”.

As Italian media question the government’s cosy ties with China, Geraci has been giving interviews playing down the geopolitical significance of Italy possibly becoming the first country among the Group of Seven – and the first founding EU member – to agree to a belt and road deal.

He has also blamed the European Union for failing to reach a better trade deal with China.

“We are acting in the interest of our companies, which have always had trouble winning contracts abroad. We are now helping them,” Geraci told La Stampa.

“Italy will be able to export its products, conclude contracts and receive orders with greater freedom,” he said. “Closer cooperation with China is an advantage for investors.”

Italy lining up Chinese deals despite deputy premier’s security warnings

Geraci’s China-friendly stance should come as no surprise to those who have read his reverential writing on China in numerous publications. In his last Caixin article, published in August 2017, Geraci’s focus was the initiative that he now wants Italy to join.

“The Belt and Road Initiative has probably become the new thinking for China to convince international partners about its true, genuine intention to open up trade and investment,” he wrote.

In another column, earlier that year, Geraci bluntly outlined how Italy and China would mutually benefit from cooperation. “A win-win situation has emerged: what China needs is to improve its own image, and what Italy needs is capital,” he wrote.

Italy should take back the Mona Lisa, deputy PM jokes

Much of the last decade saw Geraci working in and out of eastern China as an academic. From 2009 to 2018 he was an adjunct finance professor at Zhejiang University in Hangzhou. He also held professorships at the Ningbo campus of the University of Nottingham, also in Zhejiang province, and New York University’s campus in Shanghai.

Those career stops helped him to see the opportunities for Italy in joining the belt and road scheme – better thought of there as the “New Silk Road”, a nostalgic evocation of Marco Polo, the 13th century Italian explorer whose writings made Europeans aware of the wealth and vastness of China.

But Geraci’s investment-first approach to managing Italy’s relations with the Asian superpower has drawn criticism at home, with parliamentarians demanding to know why the government did not let them vote on a potential deal before Xi’s visit.

German opposition to Italy’s belt and road deal with China ‘unfair’

“What does promotion of export have to do with a [memorandum] that has no legal value and serves only to take sides politically?” asked Ivan Scalfarotto, a member of parliament from the major opposition faction, the Democratic Party.

“The problem is that you [Geraci] are not dealing. You are bowing,” Scalfarotto said.

Ivan Franceschini, a Venice-based China watcher who last year mobilised academics to criticise Geraci’s China-friendly stance in a joint letter, said that “to blindly provide the Chinese authorities with such a powerful endorsement [of the belt and road] is wrong”.

It was misguided, he said, “not only politically, but also ethically”, especially considering “the increasingly authoritarian tendencies shown by the Chinese leadership in the past few years”.

Italy signs up for belt and road infrastructure summit in China

Opposition to an Italian belt and road deal has also been voiced from abroad. Like the EU, the United States has characterised the initiative as a debt trap at best, and a neocolonial project at worst.

White House National Security Council spokesman Garrett Marquis warned that joining the belt and road scheme was unlikely to help Italy economically and could significantly damage the country’s international image.

The Conte government is understood to be planning to give Chinese companies greater access to the port of Trieste – one of the region’s busiest, with access to the Mediterranean – as well as further cooperation between the leading electricity providers of both countries.

Geraci, however, said the international alarm mystified him. “Honestly, I’m a little surprised,” he told Italy’s main finance newspaper, Il Sole 24 Ore, last week. “I wonder where so much concern comes from.”

China tells US to mind its own business over Italy’s belt and road plan

Geraci’s embrace of China dovetails with his Euroscepticism – an attitude that is a headache for some EU members.

For instance, when Germany’s leading airline, Lufthansa, was considering buying Italy’s struggling flagship carrier, Alitalia, last year, Geraci scoffed at the idea. He said he would rather sell part of the Italian airline to Chinese investors.

But Geraci insists he has been a China critic, too.

When asked if his personal connection with China could have swayed his policymaking decisions in the Asian country’s favour, he told La Stampa:

“I ask you to look at my posts on the internet in which I have explained how to limit Chinese acquisitions in Italy, even from the time I worked over there and was paid by the Chinese.

“I have been saying that we need to halt predatory attitudes for years.”