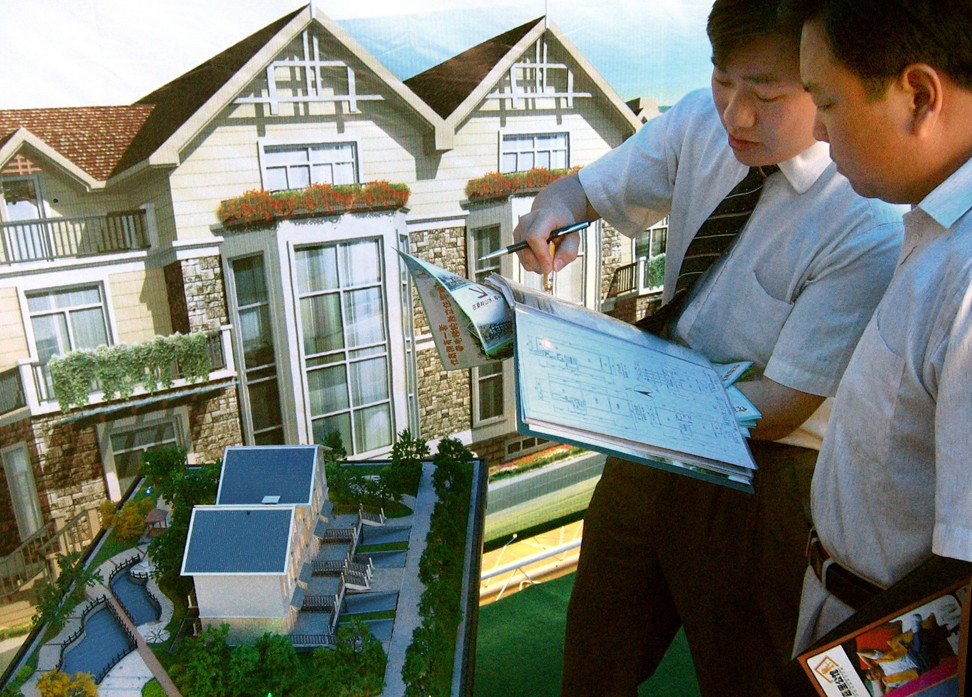

Xian in grip of housing boom after aggressive growth plan brings in hundreds of thousands of new residents

Despite central government efforts to curb property speculation, Xian’s strategy of lowering the barriers to securing residency have seen the northwestern city’s property prices soar

It came as little surprise to the young civil servant that almost as soon as he had put down the deposit for a second-hand flat in Xian, the real estate agency cancelled the transaction.

It was the third time this had happened and the 28-year-old, surnamed Yan, viewed each cancellation as an omen.

After each of his attempts to complete a housing purchase, the price of the property had jumped, and the price is now 30 per cent higher than it was three months earlier.

“The sellers just want to wait for the price to rise further,” Yan said. “They have seen that hundreds of thousands of new qualified buyers are heating up the property market.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping has repeatedly called for houses that “are for living in, not for speculation”, and during a meeting at the end of July, the Politburo, China’s top decision-making body, said it was determined to resolve the housing problem and “firmly” curb rises in property prices.

But local government have come up with increasingly creative ways to circumvent central government policy prescriptions, often leading to the opposite result to the one Beijing wants to achieve.

Xian has found a particularly clever way to bypass Beijing’s crackdown on property fever by sharply lowering the barrier to new city residents.

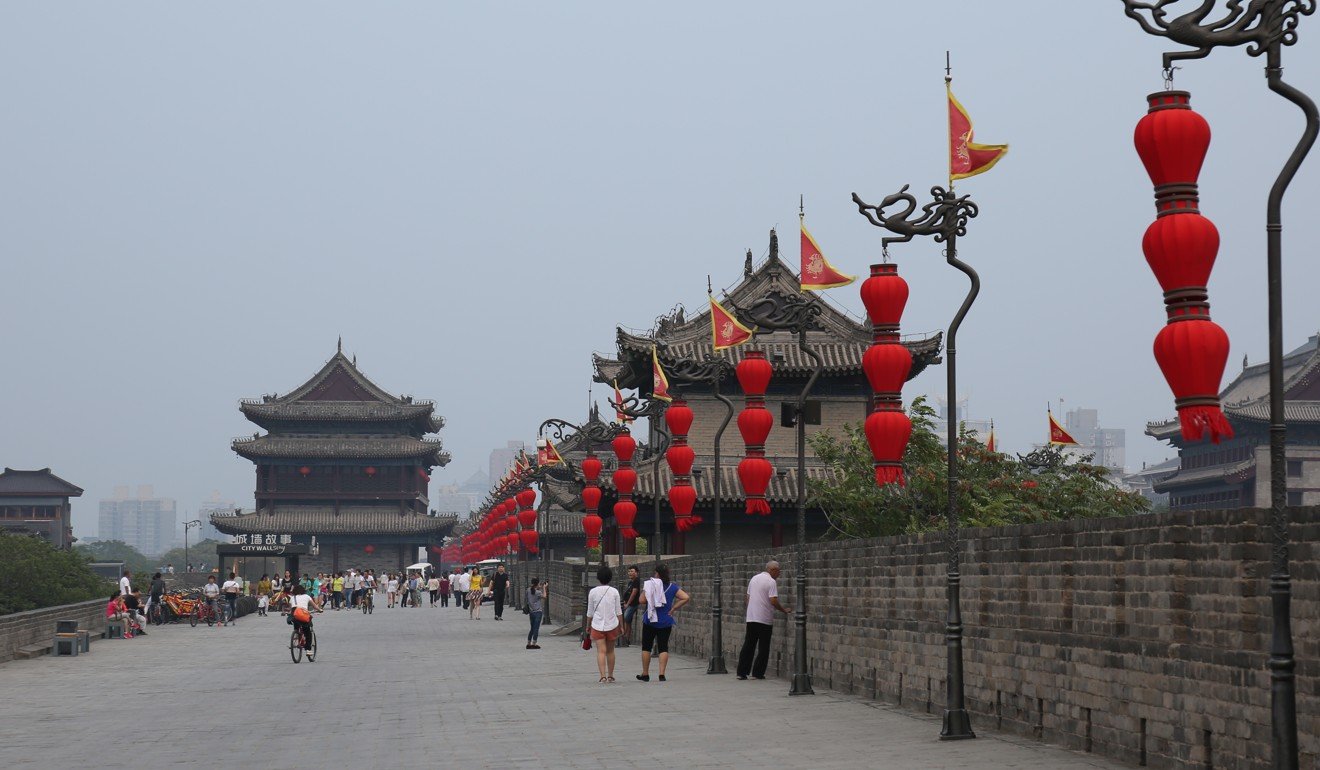

The ancient imperial capital has aggressively eased restrictions on getting a local hukou, the household registration for mainland citizens that is also the entry permit to the local housing market.

Now people will only need a technical secondary school diploma, rather than a university degree, to secure residence rights.

The resulting influx of new residents has increased housing demand and therefore prices.

Since March last year, when the city lowered the barrier, the number of registered residents has jumped by 800,000, more than the rise in the city’s population from 2005 to 2015, and equivalent to the population living within the Boston city limits, according to government data.

The move has also helped boost the city’s economy, which is highly dependent on the property market. Last year, real estate investments accounted for 31 per cent of the city’s GDP, the fourth highest ratio among the 30 largest Chinese cities, according to a report by state-run China Real Estate News.

Nowadays the Xian natives are just watching us outsiders scrambling for houses

The ancient capital has felt the vitality of fresh demand.

On the first Saturday of June, around 2,000 prospective buyers flooded into the sales centre of “Flower City,” a new residential project on the east side of Xian and beside the main route to a big landfill, to bid on fewer than 600 units for sale.

The number of customers would continue to climb as time went on given that this was the very first day of the application period.

“Nowadays the Xian natives are just watching us outsiders scrambling for houses,” joked a male buyer, who was originally from Tianshui, in Gansu province, but now holds a Xian hukou. “I chatted with some buyers, few of them are natives.”

According to a study published in March by CRIC, a real estate consultancy, three in four homebuyers in Xian were new residents, and so far this year the supply of new houses has not kept pace with demand.

As a result, the price of a second-hand home price is now higher than that for a new unit in Xian. Last month, the average price of a second-hand house was 15,200 yuan (US$2,230) per square metre, exceeding the average price of 12,500 yuan for a new home, according to real estate big data provider Cityhouse.

In June, the average property price in Xian was 101 per cent higher than it had been a year earlier, a growth rate much faster than any other first or second-tier cities, according to the latest statistics from the China Academy of Social Sciences.

“The additional registered population increased demand, which was the major cause of soaring property prices,” a Xian statistics bureau spokesman said during a press briefing in April.

But the city has not reversed the policies that keep increasing the number of new residents.

As of May, the municipal government had relaxed its residency rules four times this year. Under the new policies, once a person is registered as a Xian resident, the rest of his or her family can move into the city.

Applying for a new hukou is almost effortless. College students anywhere in the country can simply submit photos of their national ID and student cards to the official account of the Xian police on social media app WeChat and get their new hukou by express delivery a few days later.

Last week, a video went viral on China’s internet showing a police officer using a megaphone to urge shoppers at a market in the city to get a local hukou.

The Public Security Bureau confirmed the authenticity of the clip, adding that some police officers have gone door-to-door to promote the residency policy.

“The increase in registered residents has become an indicator for our performance evaluation,” Yan, who works for the local government, explained. “So every district official is under pressure to find more people to apply for a Xian hukou, no matter who they are.”

During a mobilisation meeting in February, the Xian police set a clear a target to increase the number of permanent residents to over 15 million in three years, meaning the city would have to add nearly 6 million people.

A banner in the hall clearly revealed the objectives of the campaign: “The Battle for Talent and Population”.

Xian Housing Authority launches probe into alleged rigged sales lottery at major development

In the same month, the National Development and Reform Commission approved a plan to develop Xian, the starting point for the ancient Silk Road, as the ninth national central city, the highest urban ranking, which allows Xian to get more resources from the central government as well as giving the city more political clout.

Zhao Xinzheng, associate professor at the school of urban and environmental sciences at Northwest University in Xian, has experienced first-hand the local government’s enthusiasm for a larger population.

“The police station only took five minutes to approve my son’s hukou in Xian,” he said. “Four years ago, they refused to do it.”

Without a hukou, residents are denied access to a range of public services, including – in the case of children – local schools.

“Becoming a national central city requires the population reach a certain size,” Zhao said, “so the incentive for loosening hukou rules has more to do with the city’s economic vision.”

The local authority’s efforts to expand the population have been given an extra impetus by the local economy’s recent travails.

Through the end of 2016, investment in the city had declined for 16 straight months, according to the municipal government work report. During 2015, total fixed asset investment slumped by 12.5 per cent, official figures show.

And over the decade to 2017, the population of Xian, the largest city in northwest China stagnated.

But the tide began to turn when Wang Yongkang was named municipal party secretary in December 2016.

In January 2017, Wang set a goal of increasing local gross domestic product to 1 trillion yuan (US$150 billion) by 2020, 253 billion yuan more than the 2017 figure.

In the same month, he also announced that Xian had taken over all of the Xixian New Area, three-quarters of which had originally been part of the city of Xianyang. Annexing 658 square kilometres of territory from its neighbour gave the provincial capital 605,900 more residents.

It is rare in China for a national level new area – an urban district that gets special support from the central or local government – to be put under the administration of a city and speaks to the national support for Xian’s development plans.

According to the Shaanxi government work report, establishing a “Great Xian” is one of the province’s top missions.

With the province’s support, investment in Xian rose 12.9 per cent last year to 755.6 billion yuan, the government figures showed.

In the first quarter of this year, actual year-on-year GDP growth in the ancient city rose above 8 per cent.

The economy of Xian now accounts for 36 per cent of provincial GDP, a ratio that has been increasing over the past decade.

China’s Xian chokes on smog specks ‘harder than steel’

But Xian’s population-based growth strategy is having a devastating effect on smaller cities and towns in surrounding areas.

Of the 11 biggest cities in Shaanxi, seven have suffered a net outflow of population in the last year, according to a report by financial services firm Zhongtai Securities.

After handing over Xixian New Area to Xian, Xianyang’s economy shrank 2.3 per cent in 2017 as the number of permanent residents fell by 600,600, according to the local government data.

Some cities in the other provinces have experienced similar problems.

The population of Qingyang, a Gansu city which has China’s largest oilfield, had a net outflow of 457,800 people in 2016 and saw its GDP drop by 1.9 per cent that year.

The population of Tianshui, the hometown of the male Flower City buyer, had a net outflow of 383,000 people in 2016, accelerating from 360,000 people the previous year, according to the government data.

As the city’s population shank, the city’s growth rate tumbled to 4.5 per cent last year, only half of the 9.2 per cent recorded two years earlier, official data showed.

In October 2016, Tianshui’s average property price was 7,109 yuan per square metre, higher the 7,005 yuan rate in Xian at that time, according to market research firm AskiCI Consulting.

“Property prices in Tianshui were even more crazy than Xian,” the male buyer said. “Even though Tianshui is only a fifth-tier city and Xian is a capital.”

But the picture has changed radically. Last month, Tianshui’s average new house price hovered around 7,300 yuan per square metre, little changed from two years earlier, while the average price in Xian has jumped to nearly 13,000 yuan, according to data from Jiwu, a real estate consultancy.

It would be hard to attract investment if housing and land values do not rise

Zhu Yu, general manager of CRIC’s Xian office, said the city was relying on a population-oriented growth strategy to ensure a quick success.

“Manpower is the cornerstone of development potential,” said Zhu, “so the city is leveraging the prospect of a larger population to woo more enterprises and investments.”

“The aggressive economic strategy offers the prospect of asset appreciation in the future,” he added, “pushing up expectations for house prices in Xian.”

Xian is not alone in its hunt for new residents. Since last year a group of second-tier cities – such as Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, and Hangzhou, capital of Zhejiang province – began implementing a series of measures to lure people to the city such as streamlining the process of obtaining a hukou and granting subsidies to new residents.

Property prices in the two cities had risen by more than 40 per cent year-on-year, according to the figures for April.

Although Beijing has repeatedly tried to curb housing speculation, CRIC’s Zhu said that local governments had little incentive to halt price rises given the cities’ development ambitions.

“It would be hard to attract investment if housing and land values do not rise,” said Zhu. “The only thing the government can do is to prevent the prices from rising too fast.”

“The central government’s guidelines for ‘targeted policies’ [to combat rising housing prices] also give regional governments the space for manipulation,” he said.

Ma Ji, general manager at an architectural design firm in Xian, said he was now receiving fewer orders for factory projects, but demand for residential buildings and commercial complex designs have become the dominant portion of his business.

“Surging housing prices have awakened the land market,” Ma said.

“A larger registered population means more social welfare expenditure, but where will the money come from? From selling land or additional borrowing,” he added.

During the first five month this year, the city sold 84 parcels of land, a total of 3.26 million square kilometres (1.3 square miles), more than double the acreage over the same period last year.

This week, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, China’s top property regulator, held a meeting in which it repeated its warning to local governments to curb ballooning property prices. The ministry had delivered the same warning to local governments in May to little effect.

China reminds city officials of need for property price curbs in sign they may not be working

Just after the conclusion of that first meeting, large numbers of buyers queued outside the sales centre of Avenue One, a new property development in the Changan district of Xian, to submit their applications for a housing lottery that was held on the evening of May 24.

The same night, a leaked document revealed that dozens of local officials, who worked in housing, planning, construction and land bureaus, had already reserved parts of the units.

At 116 West Avenue in the city, many people sat on the stone steps outdoors on the first Friday of June. On the other side of the gate behind them, hundreds of customers occupied all the seats of the Xian Second-Hand Houses Trading Market; the speakers continuously broadcast calls for buyers to come to the counter.

Across the street was the newly renovated Lianhu police station, where an office for receiving residents’ complaints had disappeared, replaced by an expanded hall for household registrations.

“The fever in the Xian property market is unstoppable now,” Zhu said.

When asked whether he thought housing prices in Xian would ever drop, Yan, who is still looking for somewhere to buy, said curtly: “No.”