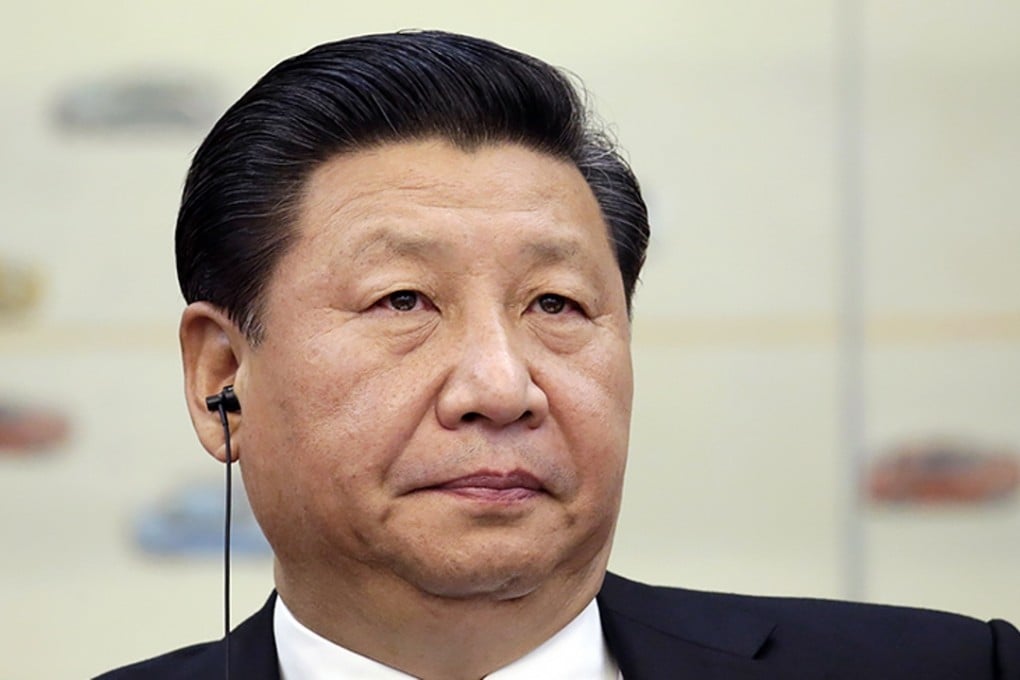

Update | China’s President Xi Jinping sends warning to influential top cadres standing in his way

President says nobody is immune from anti-graft drive, but analysts differ on who he is cautioning

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) remark in a book published on Friday, that no one will be immune from punishment for corruption, is a warning to influential retired leaders or princelings who may be standing in his way, analysts say.

While the analysts agreed that Xi was using his massive anti-corruption campaign to consolidate his power, they had different opinions on exactly which former leaders were being targeted.

Xi had, in an internal meeting in February, said no one was immune from punishment, unlike in ancient times when emperors often granted their family members or favoured officials exemptions from legal penalties.

READ MORE: In hot pursuit of China’s princelings

“Under the rule of law, no one should have the wishful thinking of being pardoned, as there is no such thing as ‘dan shu tie quan’ or ‘tie mao zi wang’,” Xi said.

His remarks were published last week in a collection of the president’s previously undisclosed internal speeches. The book was edited by the top anti-graft watchdog, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection.

The phrase “dan shu tie quan” refers to an iron certificate granting its holder immunity from punishment. “Tie mao zi wang” translates literally to mean an “iron-capped king”, referring to those who enjoyed such privileges.

Xigen Li, associate professor of the City University of Hong Kong’s department of media and communication, said different interest groups would interpret the president’s message differently.

“[But] no matter how people interpret it, it implies the power of the speaker. The tone is set for things to come in China,” Li said.