Fake story about US tycoon removed from Chinese school textbook

Move comes amid greater scrutiny of textbooks on the mainland from parents wary of propaganda being taught to their children

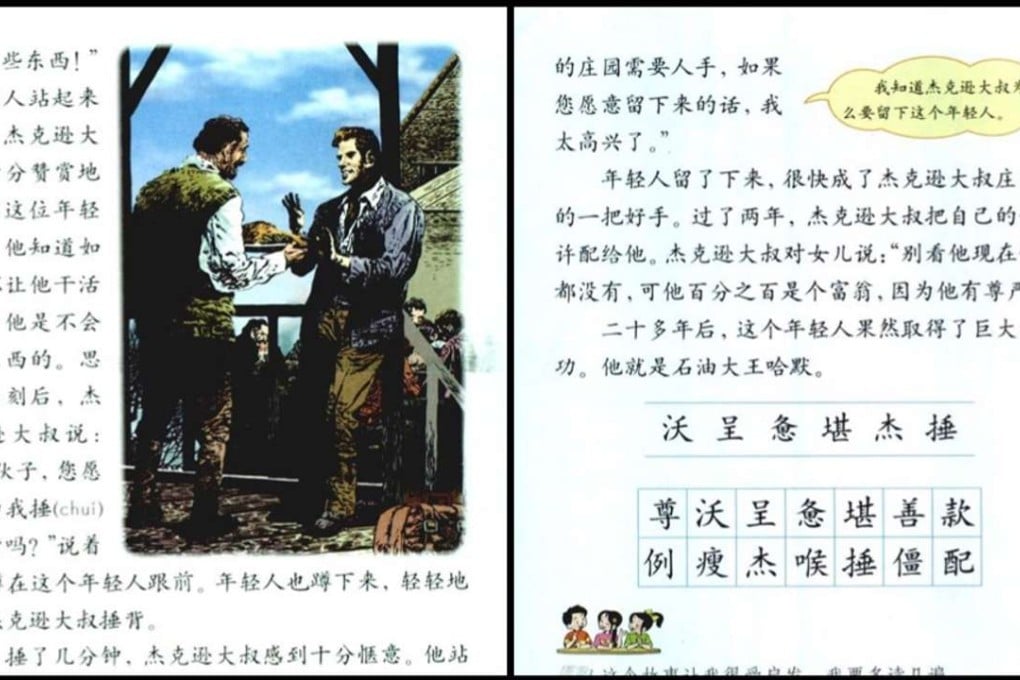

A fake story about the American oil businessman Armand Hammer has been removed from a Chinese primary school textbook, its publisher said, after parents and teachers expressed anger over the fabricated information.

A passage in the textbook said Hammer was a refugee in California as a young man who refused to take food from a town official for free. The official was touched by the young man’s dignity and independent spirit and decided to let his daughter marry him, the article said.

The story about the tycoon born at the end of the 19th century was later found to be false.

Beijing-based People’s Education Press said in a statement on its website that the passage had been taken out and it was also excluding other “controversial” articles from updated versions of textbooks.

The publisher, which has a near monopoly in producing textbooks for China’s primary and middle schools, said the story about Hammer was originally reported in a Chinese magazine in 1998 and it was later picked up by other periodicals.

The statement gave no details about the other articles that would be corrected.