Obituary | Mao Zedong’s personal secretary and biggest critic Li Rui dies at 101

- As a lone dissenting voice among China’s ruling elite, Li spoke out against Xi Jinping and the cult of personality

- In the 1980s he pushed for measures to limit the power of party officials and protect free speech

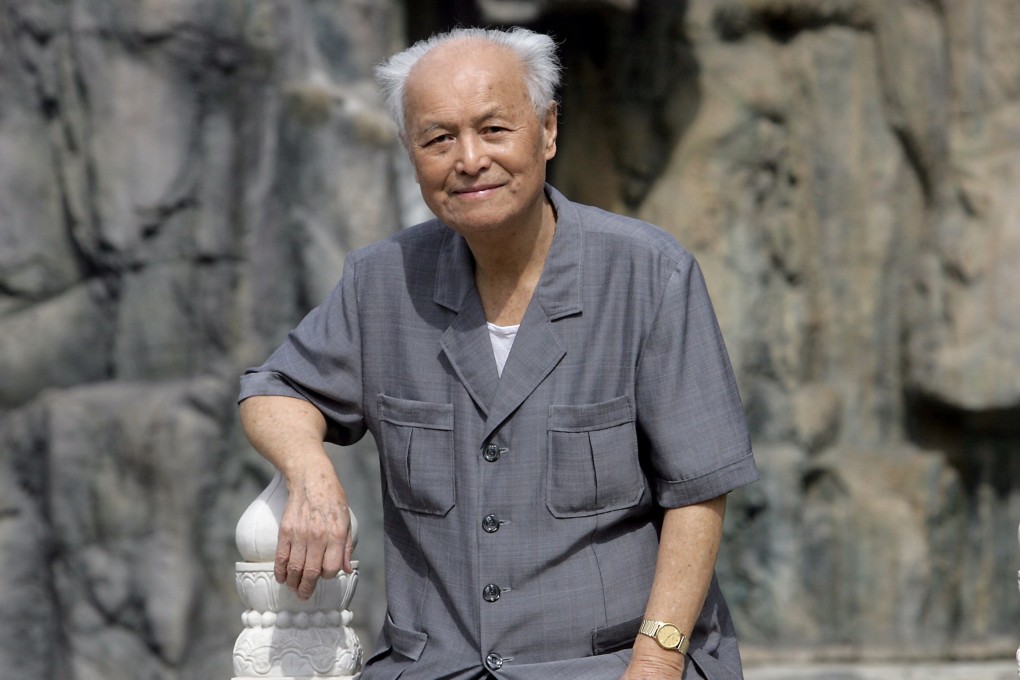

Mao Zedong’s personal secretary, Li Rui, who became one of the former Communist Party leader’s most vocal critics, died on Saturday at a hospital in Beijing. He was 101.

A bold and deeply respected figure, Li continued to fight for political reform to his final days and frequently warned of the dangers of one-party rule and unchecked power.

His death was announced in a statement released by his daughter, Li Nanyang, and confirmed by his former publisher and family friend, Wu Si. Li had been battling lung disease for several years. He is survived by his daughter and second wife, Zhang Yuzhen.

Li joined the party more than eight decades ago and helped establish the institutions of post-Mao collective leadership. But in the Xi Jinping era, he was perhaps the lone dissenting voice within the ruling elite, speaking out publicly against the campaign to promote a cult of personality around the president and some of his Maoist policies.

When the party changed China’s constitution last year to abolish term limits on the presidency – limits that were proposed by Li and put in place by Deng Xiaoping – Li suggested there were parallels between Xi and Mao.

“A country like China produced people like Mao Zedong. Now it gives birth to a Xi Jinping,” Li told Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao in March last year.