China’s Communist Party congress: all praise Xi Jinping but draw the line at Mao

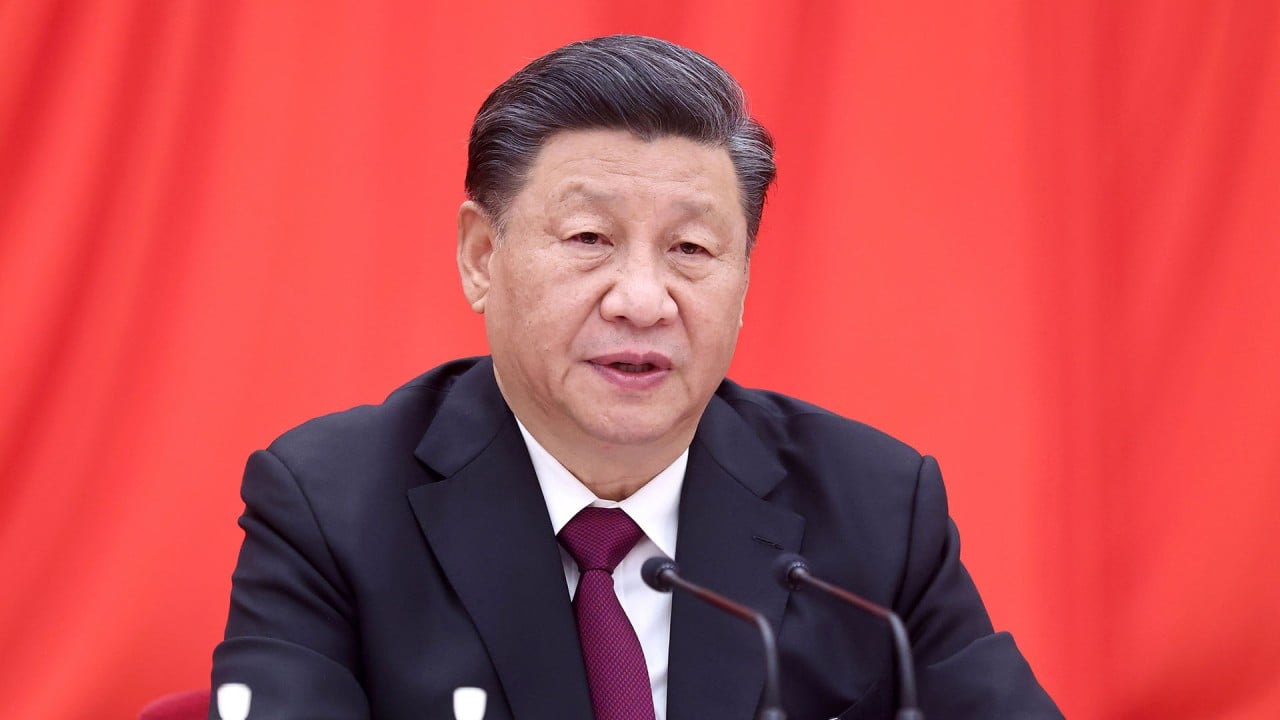

- Regional officials are stepping up displays of loyalty, with President Xi Jinping expected to stay on for third term

- But promotion of a Mao-like personality cult by over-eager officials may not always work in their favour

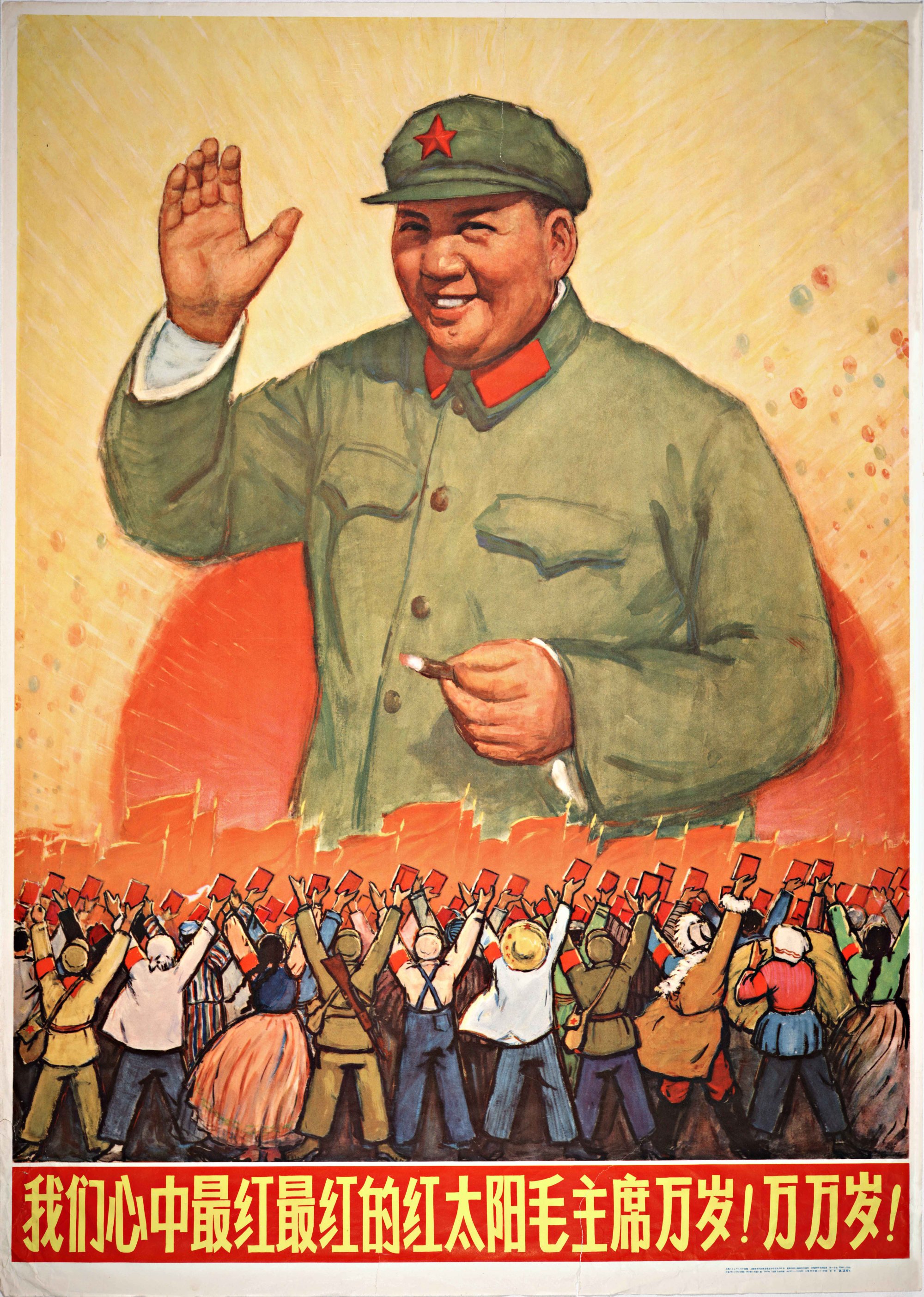

But one city’s attempt at innovative adulation ended up reminding many of the traumatic authoritarian years under Mao Zedong.

Since February, the city of Nanning, capital of Guangxi region in south China, has not only been handing out free copies of a pocket-sized book of Xi quotes, but also held multiple reading sessions on it.

The book, compiled by the propaganda department of the city’s municipal party committee, was praised by local officials and villagers as “vivid”, “easy to understand” and “easy to carry”.

However, local media reports about the campaign had mostly been scrapped by the end of April, as had happened before with some over-the-top praise for Xi recalling the Mao era.

Analysts say the distribution of the Xi pocket book and photos showing the populace – from peasants to students – engrossed in it, reflected more an opportunistic move by local officials than a genuine outpouring of public support.

Xi’s China is so different from Mao’s China ... maybe the political culture is not

“We have long passed the period during which official propaganda had a guaranteed buy-in from the public,” said Li Ling, lecturer for Chinese politics and law at the University of Vienna.

“The Nanning government stunt was meant to signal public support for the exalted party ideology.

“When the signal was badly received and recognised as fake, of course there is no point for the propaganda outlet to keep signalling it.”

Richard McGregor, senior fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, was of the same view.

“Xi’s China is so different from Mao’s China. But while the country might be different, maybe the political culture is not,” he said.

“I can’t imagine, though, that there are grass-roots demands for these books.

“It’s more a case of local officials performing for the leader, not so much to reinforce Xi’s position, but to secure their own, and future promotions.”

The pocket book campaign came as preparations entered the final phase for the Communist Party’s 20th national congress this autumn.

This edition of the five-yearly gathering of China’s political elites is likely to see a major power reshuffle involving hundreds of high-level public officers, top party cadres, ministers, generals, regional chiefs and state-owned enterprise bosses.

Xi will be joined at the event by more than 2,300 other delegates in voting on the Central Committee, the party’s top policymaking body. The committee’s 200 or so members will then decide on who sits on the Politburo and its Standing Committee, the party’s centre of power.

Meanwhile, provincial chiefs around the country have publicly showcased their loyalty to the party in various ways, often lavishing personal praise on Xi.

A communique at a Guangxi party conclave in April said officials must stay loyal to, defend and follow the leader “forever”.

China’s new generation of leaders will have to pass ‘the loyalty test’

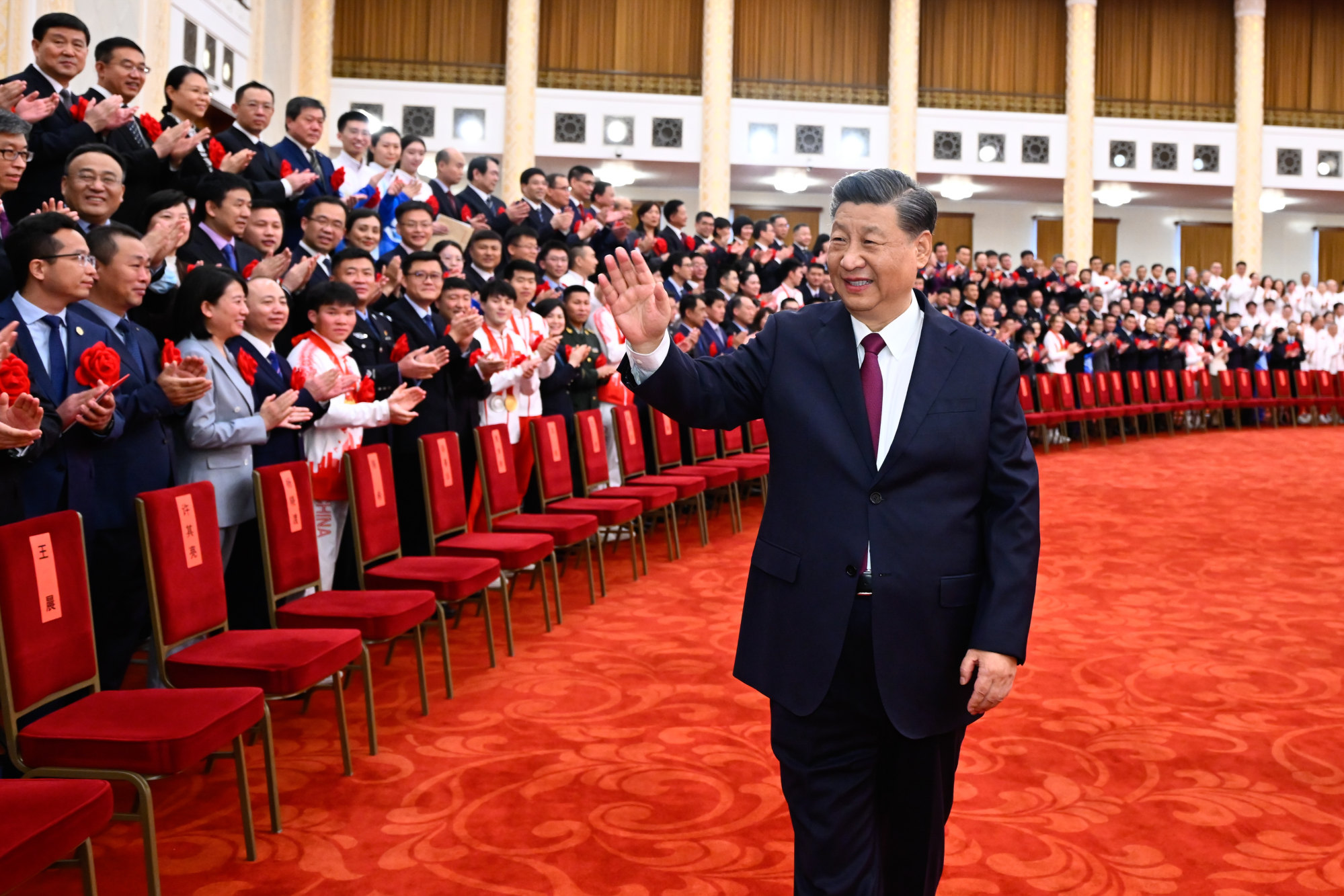

Even sporting achievements have been attributed to Xi’s guidance. Chinese athletes’ record medal haul at the Beijing Winter Olympics owed much to “a wise leader”, the delegation’s secretary general Ni Huizhong said during a ceremony to celebrate the feat in April, attended by Xi.

An increasingly emotional show of support for Xi has underlined the limit of the party’s constraints against the cult of personality, said Deng Yuwen, the former editor of a party newspaper who now lives in the United States.

“The party’s constitution did ban the cult of personality, but you don’t hear any senior officials talking about it,” he said. “The trend was so obvious since 2016 when he was anointed the core that everyone in China looked away. So things like the pocket book are no surprise at all.”

The same year, the top party leadership headed by Deng Xiaoping slapped a two-term constitutional limit on the state president’s time in office. That term limit was lifted by lawmakers in 2018, the same year Xi’s thought was enshrined in the constitution.

With no clear successor in the top echelons of the party, Xi is expected to stay on for a third term as party leader, the first to do so since Mao’s death in 1976.

“To a certain extent, Xi needs the public show that proves he has the support of the entire party for his new term before the 20th party congress,” Deng said. “But the show of loyalty won’t be the only quality Xi looks for when he promotes officials in the autumn. He would also look into their competence and connections.”

Also in 2016, Tianjin party chief Li Hongzhong famously declared that “non-absolute loyalty means absolute disloyalty” as he pledged support for Xi. Li, too, won a Politburo seat a year later.

But the path of Xu Shousheng, former party chief of Hunan province, turned out to be less exalted.

The presentation by Xu, two years shy of retirement age at the time, was covered in great detail by provincial state media.

Later that year, Xu was appointed to a semi-retired position in the NPC. He retired two years later, and died of ill health in 2020, aged 67.