The legacy of China’s low-key ‘people’s premier’ Li Keqiang

- Despite early promise, ‘Li’s star faded’ as Xi Jinping’s influence grew, analyst says

- China’s economic, political reforms stalled as ‘people’s premier’ was sidelined from decision-making

It was barely a farewell.

“We are still faced with a complicated and challenging environment,” Li said. “I am confident that under the strong leadership of the [Communist Party’s] Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core, with the strong support of various sectors, and especially with the joint hard work of the Chinese people, China’s economy will be able to overcome difficulties.”

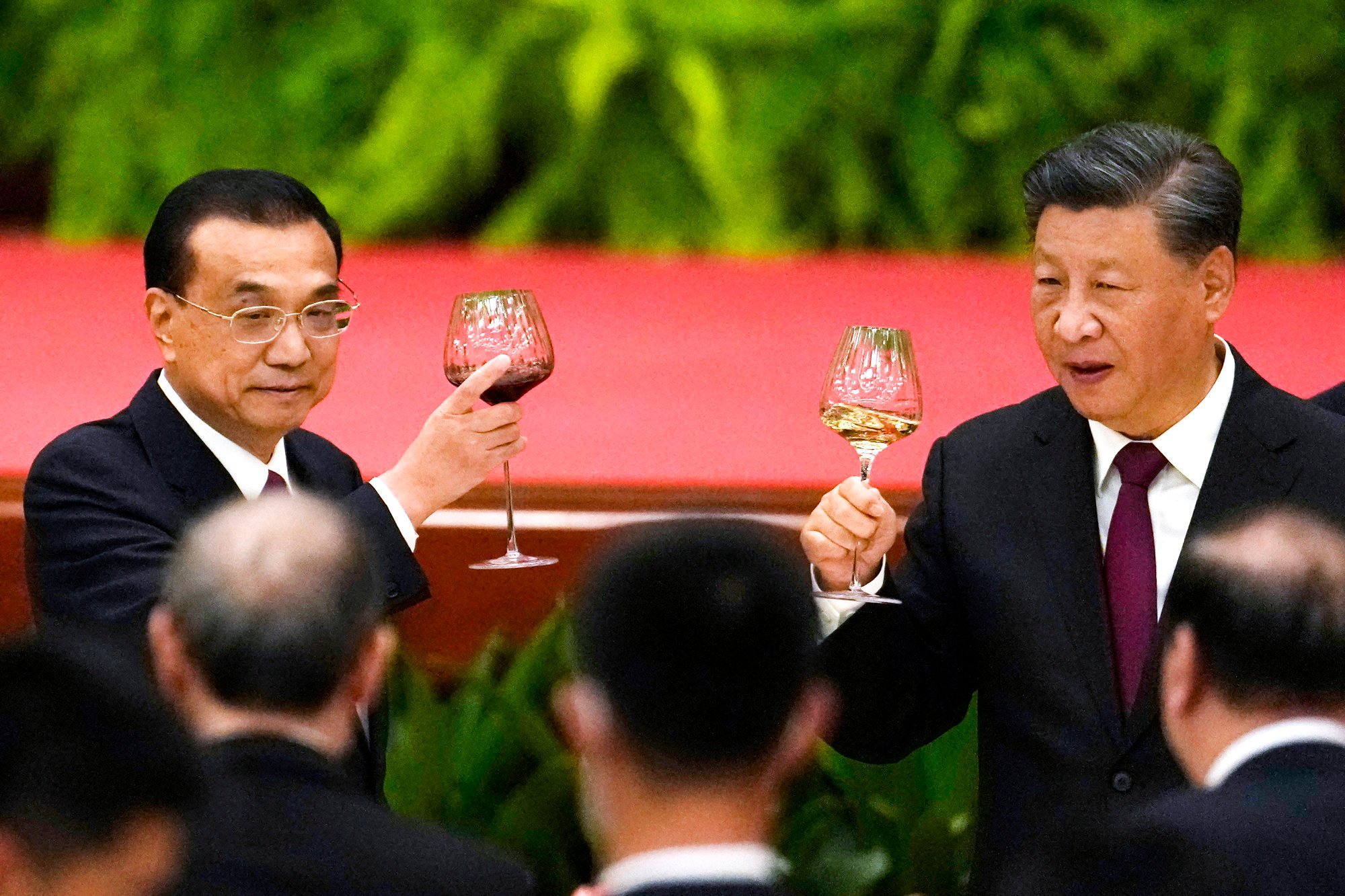

When Li became the second-highest ranking official in the party after Xi, public hopes were much higher.

In 2007, when he was the provincial party chief of Liaoning, Li told the US ambassador to China that he used more granular data, such as railway cargo volume, electricity consumption and bank loans, as gauges to defy the inflated official GDP figures for the rust-belt region.

Six years later, in the first year of his premiership, Li stepped up with what foreign media dubbed “Likonomics” – no stimulus, deleveraging and structural reform. The policy had been intended as therapy for an unbalanced economy with rising government debt and excessive infrastructure investments, after a 4 trillion yuan (US$553.8 billion) stimulus package flooded the financial system.

The idea was to trade the economy’s short-term pain for long-term gain. It was “exactly what China needs to put its economy on a sustainable path”, Barclays Capital economists wrote in a research note in 2013.

Following the pledge, the country released a national air quality action plan that required all urban areas to reduce concentrations of fine air particulate matter by at least 10 per cent. It was the first in a string of environmental campaigns.

“My overall impressions of Li Keqiang are that his heyday was at the start of Xi’s tenure while the latter was still driven by his agendas with respect to the party, internal security and the PLA [People’s Liberation Army],” said George Magnus, a research associate at the University of Oxford China Centre.

The party’s third plenum in November 2013 pledged a “decisive role” for markets in China’s economy. And for the first time, it said the private sector should be put on equal footing with state-owned enterprises.

The meeting also announced the launch of a leading party committee to oversee all aspects of comprehensive reform policies, with Xi as the team leader and Li as one of four deputy heads.

Since then, power has concentrated around Xi with the launch of dozens of central committees and leading groups that oversee activities in everything from finance to military and diplomacy.

“After 2015, I’d say, Li’s star faded and I cannot remember now anything with which I’d associate him that was either positive for the Chinese economy or different from what was expected,” Magnus said.

As Xi’s grip on decision-making tightened, Li’s economic influence began to dissipate. After Liu He – with Xi’s full support – became vice-premier in 2018 and was given control of several important portfolios and tasks, including trade negotiations with the United States, Li’s role was further diminished.

On a personal level, Li has maintained a reputation for integrity within the party’s inner circle, the Post has learned. Foreign business leaders in China who know him told the Post described Li as a genial, thoughtful person.

To the general public, Li is seen as a “people’s premier” – a role played and cultivated by predecessors from Zhou Enlai to Wen Jiabao. Li was the first central leader to visit the city of Wuhan in January 2020 when the coronavirus erupted.

In August last year, Li visited Zhengzhou after flooding killed hundreds in the city. Jobs, small companies and migrant workers were topics frequently discussed by Li, especially more recently, as China strengthened Covid-19 control measures.

At a press conference in 2020, he revealed that more than 40 per cent of China’s 1.4 billion people lived on less than 1,000 yuan, or US$5, a month, many of them without pensions or medical insurance, shining a light on the other side of China’s economic miracle.

While Li played a role more in execution in recent years, he still rolled out certain policy initiatives to reduce tax and fee burdens for small and micro enterprises. In March, he announced the government would facilitate slashing of taxes and fees by 2.5 trillion yuan for this year, after the government granted 1.1 trillion yuan in tax breaks for companies in 2021. The State Council has also introduced temporary subsidies to jobless migrant workers amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Over the past decade, China’s GDP more than doubled from 54 trillion yuan to 114 trillion yuan last year, with its share of the world’s economy rising by 7.2 percentage points to 18.5 per cent, according to Chinese government data. However, the economy has significantly underperformed recently as challenges mount, from Covid-19 to the troubled property sector.

The world’s second-largest economy also made environmental progress. The levels of the most harmful polluting air particles, PM2.5, have been cut by two-thirds in Beijing and most of the rest of northern China.

“China’s war on air pollution has yielded results beyond almost anyone’s expectations,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst with Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air.

“In terms of Li Keqiang’s personal role, my general reading of the beginning of the war on air pollution is that it gained such prominence precisely because the Standing Committee stepped in directly, with Xi assigning [then vice-premier] Zhang Gaoli the task of hammering together the first national air pollution action plan, while lending the powers of the [Central Commission for Discipline Inspection] to buttress enforcement,” Myllyvirta said.

“State Council targets as seen in the annual work plans of the government have been decidedly modest in comparison. Of course, there is very limited visibility to the role of individuals in these machinations.”

According to analysts, Zhu Rongji was known for pushing difficult reforms in the state sector. Wen Jiabao warned a decade ago that long overdue political reforms, which have become taboo in China, could not be stalled forever, or the country risked repeating historical tragedies like the Cultural Revolution. Analysts said that in both of these areas of reform, China had made limited or no progress over the past decade.

Chen Daoyin, an independent political scientist and former Shanghai-based professor, said Li should have fought for the administrative power of the State Council and defended the principle of “separation between party and government”, a concept coined by late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s to prevent party cadres meddling in government affairs.

“Unfortunately, he did not do so. Although ranked second in China’s political hierarchy, he turned out to be just an official, instead of a politician with vision,” Chen said. “Compared to his predecessors, apparently Li is the least influential.”