Opinion | Dark legacy of Britain’s opium wars still felt today amid fight against drug addiction and trafficking

Greedy traders backed by military supremacy had built a global trade in addictive drugs by the turn of the 19th century, the effects of which countries worldwide continue to battle

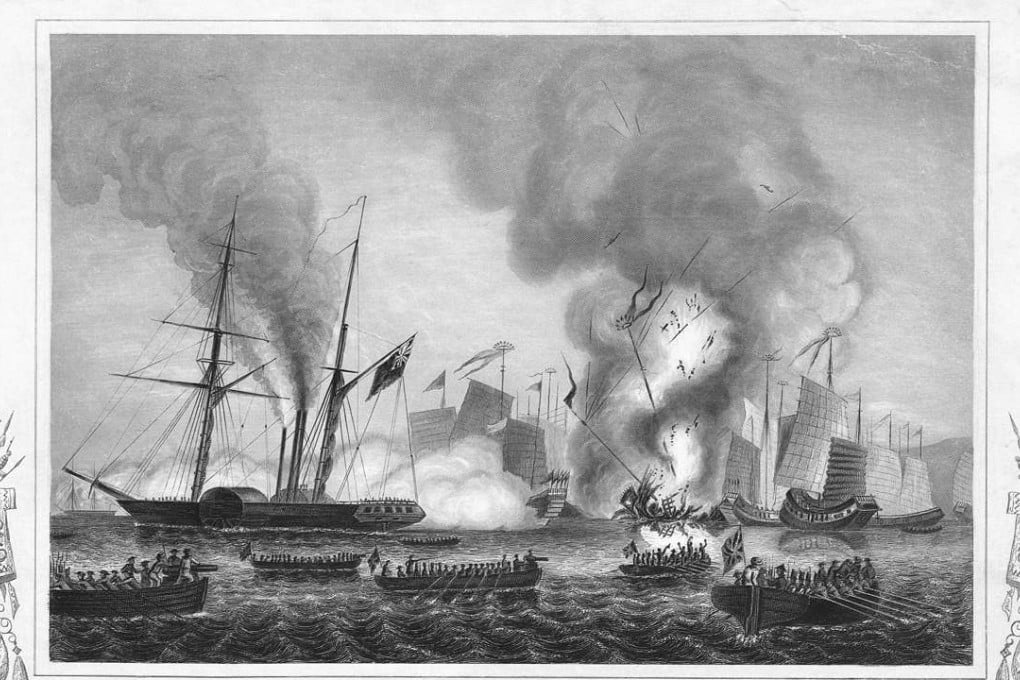

In the year 1857, on March 3, the opposition party in the British parliament, together with the progressive wing of the ruling party, successfully blocked a government attempt to escalate military action in China in order to pressurise the Qing government to open all of the country to British traders. Prime minister Lord Palmerston quickly called a national election and won a sufficient majority to reopen the war in China, this time in alliance with the French. Labelled the Second Opium War, it ended with the occupation of Beijing by joint Anglo-French forces. The Xianfeng Emperor fled the capital. The magnificent Summer Palace was burned to the ground in retaliation for the Qing army’s stiff resistance at the Taku Forts outside Tianjin which brought considerable casualties to the British invaders.

By October 1860, the Qing emperor had no choice but to accept the humiliating terms of the Tianjin treaties, which included legalisation of the opium trade in China. The large potential market had to open up to the highly addictive drug, with no legal bar at all.

William Gladstone, who came from the same Liberal Party as Palmerston, became prime minister in 1865. Gladstone had been a staunch critic of Britain’s involvement in the opium trade, calling it “most infamous and atrocious”. He also lambasted the two Opium Wars as “Palmerston’s war”. But the profit from the drug trade was lucrative and irresistible. Britain did not restrict the opium trade to China until 1906.

The outcome was that China soon turned itself into the biggest producer of opium in order to satisfy the rapidly growing demand from its addicted people. Heroin and morphine, addictive drugs manufactured directly from opium, spread to the rest of the world quickly because of the huge quantity of opium being produced. The addictive drug trade became a global problem as early as the turn of the 19th century.