Raising a star: is the Hong Kong fame game good for children?

Talent schools for kids are a hit with parents in the city, and some want fame for their little ones while others just hope for a dose of confidence

At Momo Casting Talent School in Ngau Tau Kok, bundles of energy zip around the room, their playful shrieks bouncing off the walls. Meanwhile a boy with a bowl cut sits obediently while an adult applies make-up to his face.

The school has students from three to the age of 15. All want a shot at the international fame that pint-sized Tam has gained from her America’s Got Talent performances.

Hong Kong singing sensation Celine Tam to take on fellow youngsters on America’s Got Talent live shows

Founder Momo Mo Lai-yee said: “We are more than a school for extracurricular activities. Our students have to put what they have learned to work.”

Since she started her company in July last year, Mo has helped 200 students enter showbiz, teaching children singing, dancing and acting. Before that, she worked as a booking agent for six years.

But not all children are suited for the training. Mo said it depended on a child’s personality.

Talent comes second – a child star must have a natural gift for being a people person, according to Mo.

“It’s all about how you can connect with people in the industry,” she said.

A four-session performing arts course at her school costs HK$2,500. During the course, the children are taught how casting works, including how to act and pose for photos.

Those who are “outstanding” in class may be signed as a star under the school, meaning they are given priority for movie auditions and other opportunities for shoots.

But Mo said not all parents wanted their children to become stars – some just sought to boost their son or daughter’s confidence by putting them on a stage or in front of a screen.

“I’d be lying to you if I say I didn’t want my kid to be a star,” Anna Lee Sin-ching, whose five-year-old daughter joined Momo one year ago, said.

“But I don’t need her to be a superstar. I just want to save the experience as a memento.”

A push to perform

Momo Casting Talent School is one of a number of performing arts academies in Hong Kong benefiting from a growing interest in stardom from children and parents alike, according to industry experts.

But the government doesn’t keep figures on the number of schools specialising in such training.

Private dance tutor Cony Lam Yuen-fan, who teaches children and teenagers aged two to 16, said the number of her students had grown significantly, from 10 to 50.

“Parents want their kids to do similar things to other kids. They post videos of their kids performing on social media, and other parents will then ask where their children learned to dance,” she said.

Lam said many parents who came to her hoped that their children could perform. “Parents expect their kids will have a chance to perform. They usually ask how long it will take for the kids to be on stage.”

Hong Kong-born Krystal Diaz, founder of Happy Little Singers singing school which offers classes for children aged three to six, said the increased interest from parents was partly related to the popularity of singing contests, both on television and in schools.

In June, Tam won fans around the world after performing Canadian diva Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On during the audition stages of the show. A YouTube video of her performance has now been viewed over 33 million times.

“Now parents are more open to the idea of performing arts,” Diaz said, adding that there was a sense in the past that people could get to the top without training their voices.

“In general, the influx of all these talent shows has definitely encouraged people to learn how to sing, because the exposure is there,” she said.

Diaz has heard of cases where children were under immense pressure from their parents to get on stage. But she said at her school, there was less focus placed on performance.

“We want people to sing for a lifetime, and to enjoy singing for a lifetime, and not because they want to be famous.”

A need to stand out

Another reason behind the increasing number of children heading to performing arts schools was a desire to stand out in applications for mainstream schools and universities, said Sandra Tsang Kit-man, an associate professor at the University of Hong Kong’s department of social work and social administration.

“The more exotic you are, the more interesting you become,” she said, adding that playing the piano was no longer enough.

Sharing Tsang’s views, dance tutor Lam said more parents were pushing their children to learn ballet, as “they needed the certificate to get into a better school”.

But the flip side of this trend was that young people were often burned out by the time they entered a university, and this affected their motivation to study, Tsang said.

“They get so fed up that when they join the university, they try not to study. They hate studying; they want to enjoy a new freedom,” she said.

Hong Kong’s child prodigies: three other child stars to watch out for

Tsang urged schools and parents to be “more realistic and less demanding” on their children.

Michael Eason, a psychologist at a private practice in Hong Kong, cautioned that exposure to stress might affect the development of children’s brains.

They might develop depression, anxiety issues or become more prone to substance abuse later in life, possibly even in their 20s or 30s, he said.

The level of public scrutiny on a child star like Celine Tam could have a “dangerous” side, Eason added.

“It can make her feel that her identity or self worth is dependant on that, and she will start to need validation or praise to feel that she’s worthy.”

He also cautioned against parents living vicariously through their children.

“They’re trying to realise their own dreams, maybe because they weren’t able to achieve what they wanted,” he said.

From child star to politician

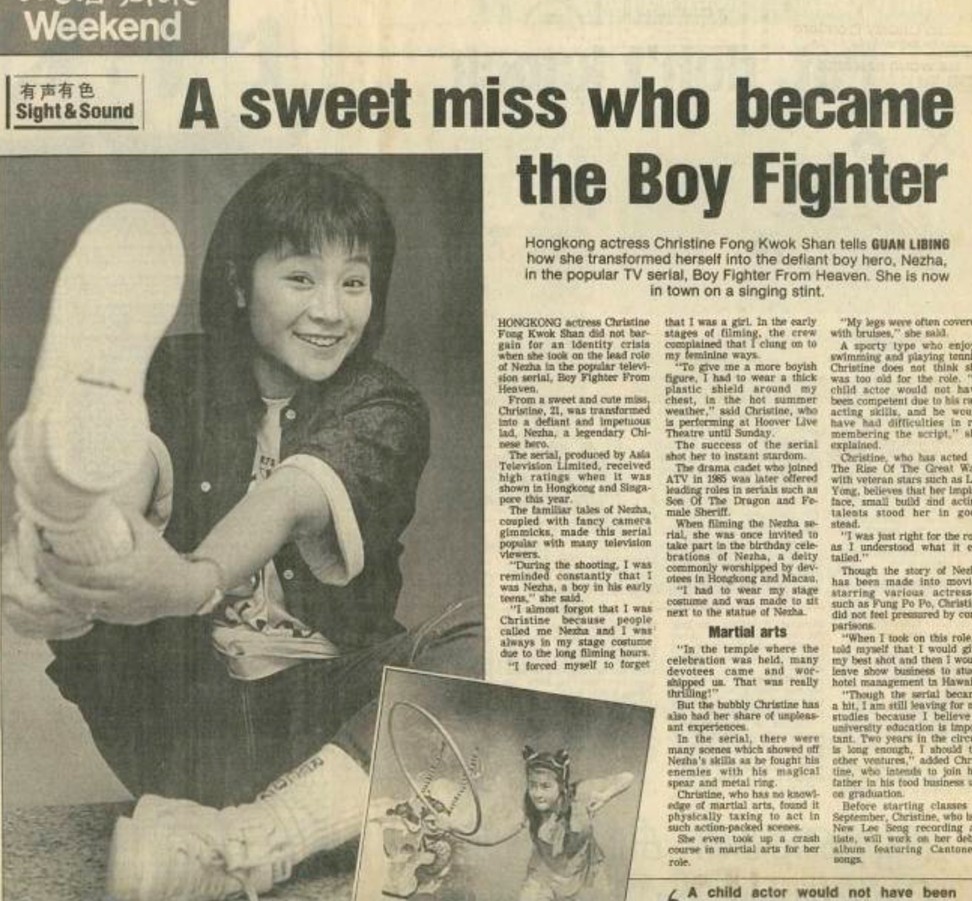

The pressure of being a young star is something Christine Fong Kwok-shan, now 51, is familiar with.

Nowadays she attracts public attention as an elected member of the Sai Kung District Council, but as a teenager, Fong shot to fame as the boy deity Nezha in the 1986 television series The Boy Fighter from Heaven.

Fong said she felt “amazing” as a star and “enjoyed the fame”, including when fans chased her down the road, and newspapers wrote gushing pieces about her boyish look.

“Life was very easy,” she said. “I consider this sort of thing as a souvenir, as a milestone for myself to look back on.”

Fong counts herself lucky – she was able to train with local television station ATV rather than being catapulted into the spotlight from the start.

She had no pressure from her parents, and she “escaped” after only a few years to enter university, aware that her androgynous appeal would only be short-lived.

Fong said there were pros and cons when it came to childhood fame. While people were now familiar with her, they often had misconceptions, assuming she was wealthy and extremely capable in public speaking.

“I escaped. I left the industry early, so nothing really bad happened in my life,” Fong said, adding that other child actors she knew experienced mental health issues later in life.

For now though, the children at Momo just want to enjoy their time in the spotlight.

After playing up for the camera with his classmates, five-year-old Fan Lok-tung said: “I want to be a TV star because the footage can last forever.”