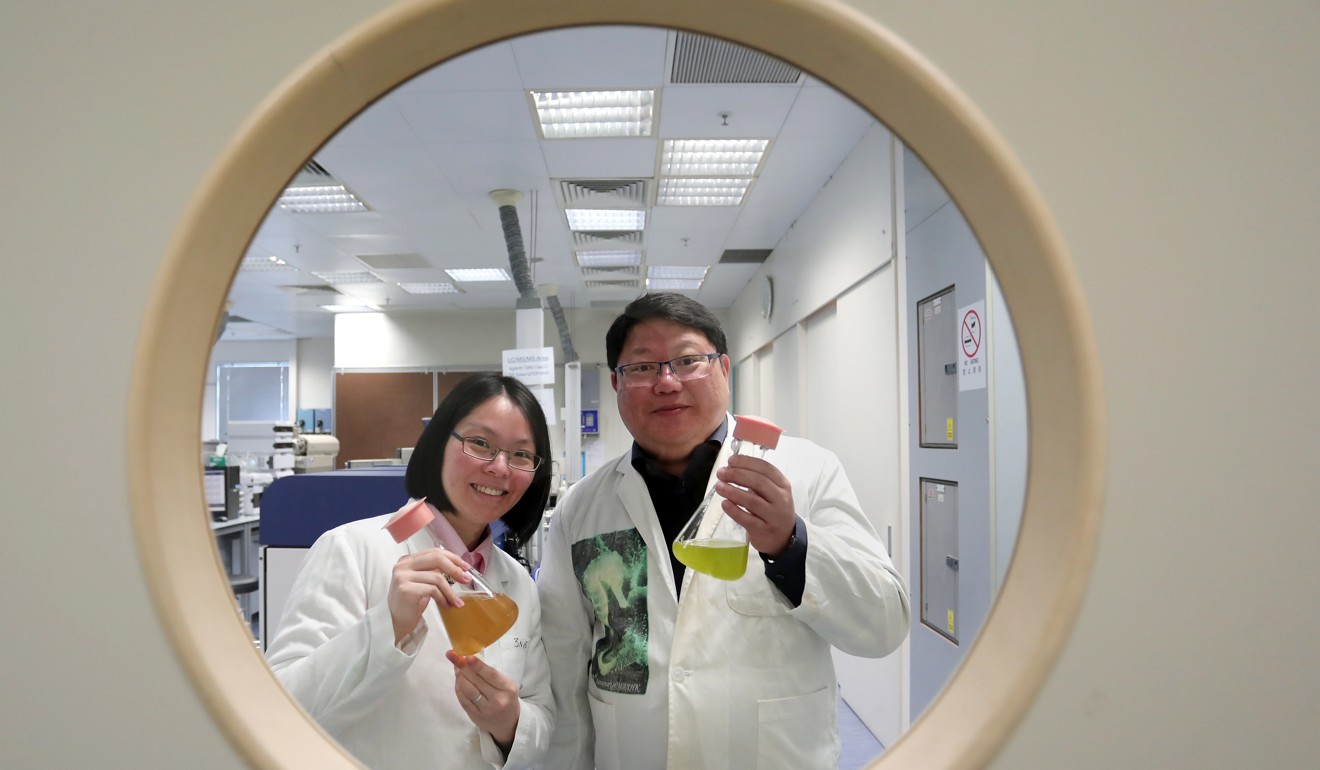

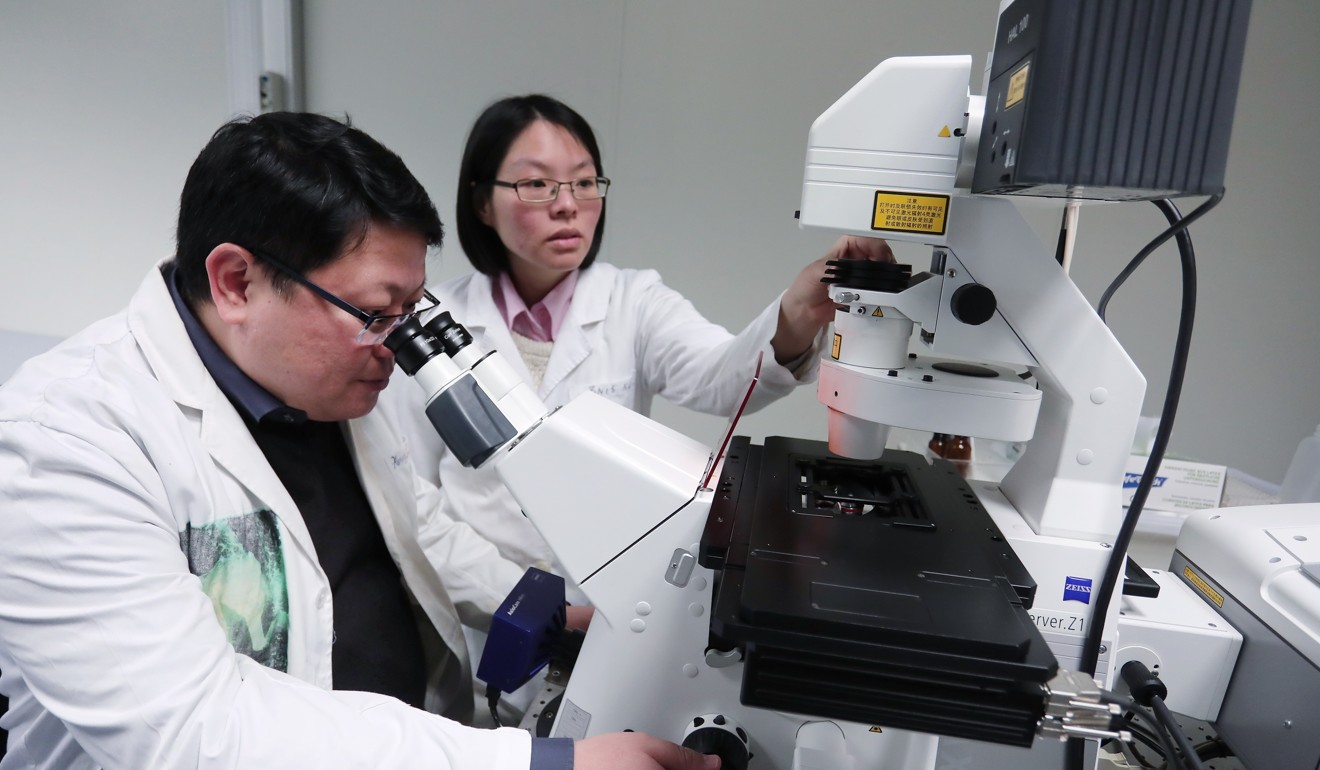

Your sunscreen may be killing marine life, Hong Kong study finds

Nanoparticles in products are found to affect algae and researchers say this can disrupt ecosystem in high concentrations

Slapping on sunscreen or sunblock at the beach may offer protection from harmful ultraviolet rays of the sun, but it could also be hurting marine life, scientists from the University of Hong Kong have found.

A new study by HKU researchers showed that tiny chemical particles in some lotions could be “silent killers” of microscopic algae, a crucial food source in the marine ecosystem.

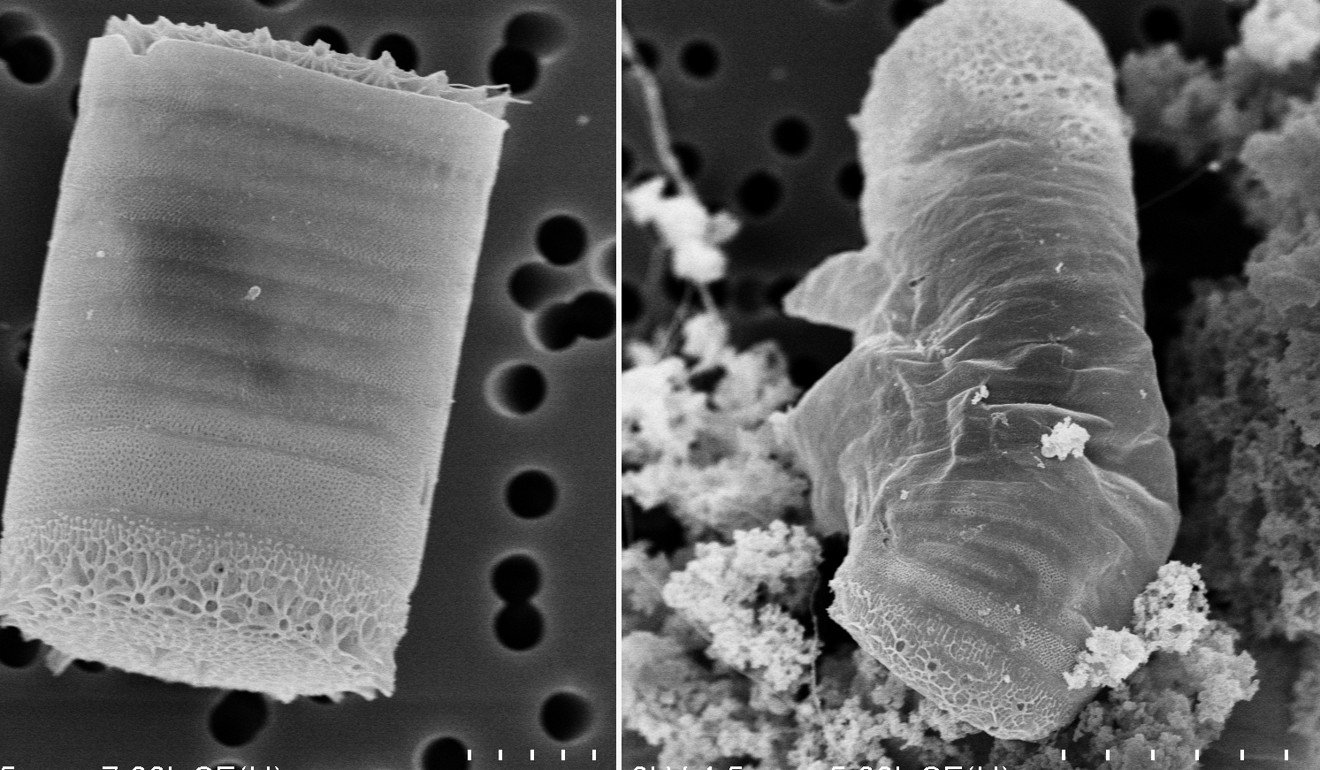

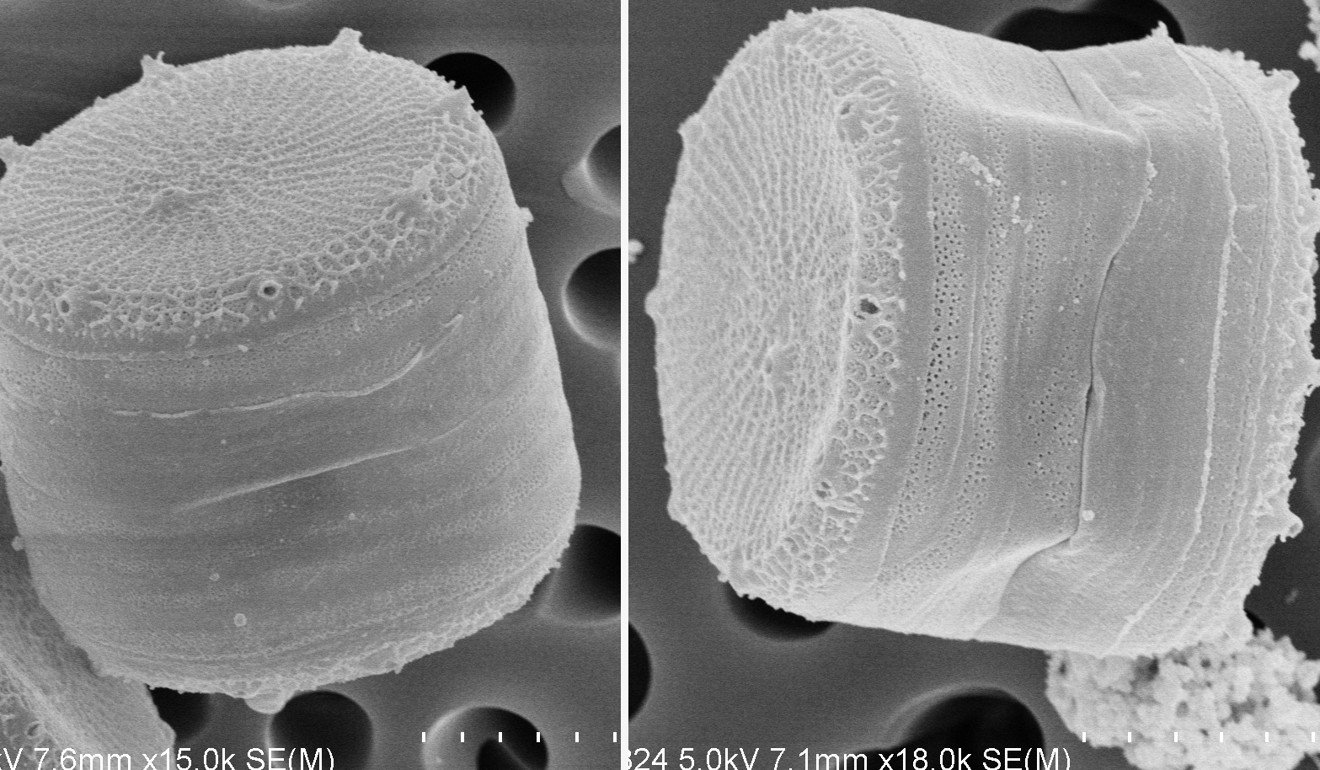

Sunscreens containing nano-zinc oxides, an increasingly popular ingredient to reduce chalkiness and tackiness in products, were found to shorten the lifespans of both freshwater and marine microalgae by between 40 and 70 per cent. The organisms were exposed to high concentrations for four days.

Half of the sample population in tests died, according to the research. The team’s findings were recently presented in paper Scientific Reports, under the publisher for leading international journal Nature Research.

The nanoparticles release a group of chemicals called reactive oxygen species, damaging the microalgae and disrupting growth.

“If there are thousands of people swimming during the summer and high concentrations are released at Hong Kong beaches, it could pose a threat to the population size of coastal microalgae,” study co-author Professor Kenneth Leung Mei-yee said.

“Microalgae forms the bottom of the food chain in the ecosystem, providing a primary food source for other marine organisms. This might cause a cascading effect, meaning other members higher up in the food chain could be affected if they have less to eat,” Leung said.

The findings back previous research that showed nano materials – 100,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair – were affecting marine creatures such as sea urchin embryos, making them more vulnerable and prone to dying.

Could tiny robots made from algae be the next big break in the fight against cancer?

Although such nano materials, widely used in sunscreens and other cosmetic products, are relatively safe for humans to use, the toxicity and impact on marine organisms are still largely unknown.

There is currently no known data on the concentration levels of such particles discharged into the natural environment.

Researchers estimated it would take some 5,700 people with sunscreen swimming in an Olympic-sized pool to bring about similarly disastrous effects. According to the team, the study’s results, the first of its kind, are not easily applicable to the real environment as other natural factors such as waves and currents come into play.

The scientists warned that local coastal waters could be at risk, especially in areas where the chemicals could travel to fish nursery grounds or nearby coral reefs already struggling to survive.

“People aren’t even aware that putting on sunscreen could be harming marine life, and if manufacturers continue to produce more and consumers keep buying them, the consequences could become more serious,” Mana Yung Man-na, another co-author of the study, said.

What we still don’t know about the oil spill affecting Hong Kong beaches

But Robert Miller, an associate research biologist from Santa Barbara’s Marine Science Institute at the University of California, said it would be unlikely for such high chemical concentrations to be released from just sunscreen alone.

“You’d need a tremendous amount of sunscreen to reach those concentrations in the real world, and it’s not realistic. However, it is possible that zinc will build up in coastal ocean waters to problematic levels due to pollution, and sunscreen would contribute to this, although it would probably be a small part of the problem,” Miller, who was not involved in the HKU study, said.

He agreed that toxic concentrations could be problematic in small bays and other enclosed water bodies with a lot of swimmers, but the chemicals released from sunscreens would be diluted in the ocean.

Around 33,000 tonnes of zinc oxide nanoparticles were produced globally in 2014 and demand is growing, according to latest available data by consultancy Future Markets Inc, which specialises in the analysis of nano materials in commercial products.

All is not lost for avid beachgoers, however, as scientists said there could be a win-win option for consumers and environmentalists.

In their study, the team also found that the toxicity to marine life could be reduced if the nanoparticles were wrapped in a silicon-based coating.

Both Yung and Leung said more research was needed to determine how the coating would react with other nano materials and marine animals. Once that is achieved, they can make recommendations to manufacturers on how to produce more eco-friendly sunscreens.

Miller said the coating would only slow down the dissolution of the nanoparticles, but the particles would still ultimately dissolve and accumulate in the environment.

“The fact that a coating makes the nanoparticles less toxic in the first few days when they enter the water is not a significant fact, in my opinion,” he said.

Another problem was the scarcity of regulation for such nano materials, which only appeared on the commercial scene in past decades, said John Giesy a visiting professor of HKU’s school of biological sciences, and another co-author of the study.

Manufacturers are not required to disclose how much or how they use the materials, and toxicity tests for the nano materials have only been established in the United States and in Europe.

“Nobody’s really monitoring what’s out there. I call it the yin and yang of chemicals. Everybody wants the benefits and their useful properties, but they always have a negative side and that’s just generally not considered, until we get to the point where we have a real problem,” Giesy said.