Sort your rubbish properly, Hong Kong’s glass recyclers tell residents amid supply and waste management woes

- Materials such as ceramics and porcelain end up in collection points meant only for glass

- Delay in waste charging law means people have less pressure to manage what they throw out

The stench of stale liquor lingers in the air at a dusty recycling yard in Hong Kong’s Lung Kwu Tan in the New Territories. Tonnes of waste glass are being pulverised into grains of sand by high-frequency shock waves, and piled neatly into high mounds.

Delvin Cheng Chung-wang, project manager at Baguio, which operates the plant, said their biggest challenge was in sifting through waste glass and sorting processable items from others.

“People think anything that looks like glass is glass, so there’s everything in here. Ceramics, porcelain, crystal, full bottles of ketchup, wine or soy sauce and, of course, just everyday trash like aluminium cans and plastics,” he said.

“If people really sort through their rubbish properly before disposal, recycling can be done so much better. Public education must really be strengthened.”

Baguio is one of two glass management contractors hired by the government through open tenders in 2017 and last year to provide effective collection and proper reuse or treatment of glass containers. The waste is then turned into reusable materials.

China’s waste ban has rocked the recycling world and revealed Hong Kong’s dire record

Hong Kong sent 10,733 tonnes of municipal waste to landfills every day in 2017, with glass – mostly bottles – comprising about 300 tonnes. The government wants contractors to help increase the recovery rate of such items to 50,000 tonnes a year, or about half of the amount generated locally.

Following commencement of the services, more than 13,000 tonnes of waste glass containers were collected by the two contractors in 2018, a 60 per cent rise compared with 2017, according to the Environmental Protection Department.

Financial support for such operations is part of a string of coordinated efforts by authorities to ramp up the city’s dismal recycling network before mandatory volume-based waste charging comes into effect.

Baguio’s facility now handles about 40 tonnes – roughly 120,000 bottles – between Hong Kong Island and the New Territories. But even if the plant has the capacity to take in up to 100 tonnes per day, the company is not collecting enough supply.

Frustrated with government’s recycling services, residents take matters into own hands

A “producer responsibility scheme” mandating producers to take on the costs for collection, recycling, treatment or proper disposal of glass drink containers is pending final stages of legislation.

Once this is passed, manufacturers and importers will have to pay the government HK$1 (US$0.13) for every 1 litre bottle. The idea is to pool funds to subsidise recycling operations such as those run by Baguio.

The department said the proposed HK$1-per-litre level reflected collection and treatment expenditures, as well as administrative costs.

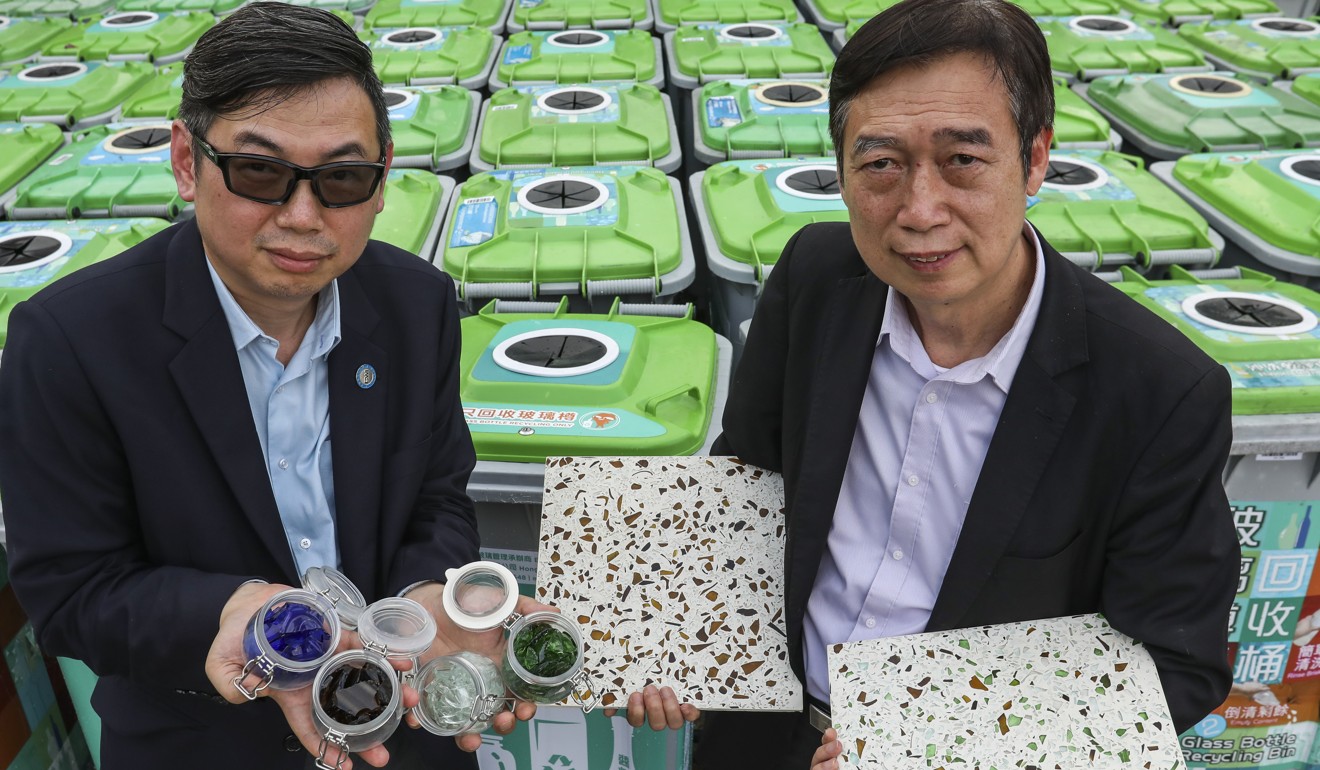

But this amount was not enough, said Simon Chu Ping-kwong, director of Glass Reborn, the government’s other contractor, which collects glass in Kowloon.

“It would really help us more if the fee was set higher … maybe about HK$2.50 a litre,” he said.

Glass Reborn processes about 20 tonnes of glass per day, which adds up to more than 7,000 tonnes in a year.

Green groups say new waste charge law lacks clarity on exemptions

The glass is crushed into sand for local use or shipped off as cullets to Southeast Asia.

As part of their five-year contract, they must meet a first-year target of 5,500 tonnes and supply 250 tonnes of sand to the government’s public fill banks. This mark is raised exponentially each year.

While sorting and logistics costs are the highest, Chu said a more pertinent issue was supply. “The hardest part is collection.

“We are actually suffering from the late implementation of the waste charging scheme. The government expected much more supply.”

We are actually suffering from the late implementation of the waste charging scheme. The government expected much more supply

The plant, Chu said, needed to collect and process at least 600 to 700 tonnes of glass bottles per month to break even. At the current rate, it is only able to eke out a tiny profit, if any at all.

Angus Wong Chun-yin, head of policy advocacy and campaigns at the World Green Organisation, an NGO, said the absence of a volume waste charge on households meant there was less pressure on people to recycle and reduce the waste they throw out.

Waste disposal charge will cost a typical Hong Kong family HK$51 a month

“The government can still consider providing more incentives to encourage residents and businesses to recycle or promote such behaviour,” he said, citing more deposit schemes for bottles as one example, or handing out small gifts or rewards to collectors who meet targets.

The implementation of mandatory waste charging was initially planned for 2019, but has since been delayed for a year.

For now, recyclers will have to get creative.

“We’ve actually launched a scheme to give out free bags of rice to those that help collect at least 40 bottles a day,” Baguio’s Cheng said. “It’s been really popular with the grannies.”