Exclusive | Relocating Hong Kong brownfield businesses inside buildings is a possibility officials will finish studying before mid-July

But who would develop and operate the buildings – and how that might affect rents – still needs to be discussed

Consolidating businesses spread across large tracts of Hong Kong’s damaged farmland into specially designed industrial buildings is a possibility officials expect to finish studying before mid-July, the Post has learned.

The feasibility studies are widely viewed as vital to releasing land for development and would suggest practicable designs for such buildings. But who would develop and operate the buildings would affect how expensive the rents would be, and still needs to be discussed.

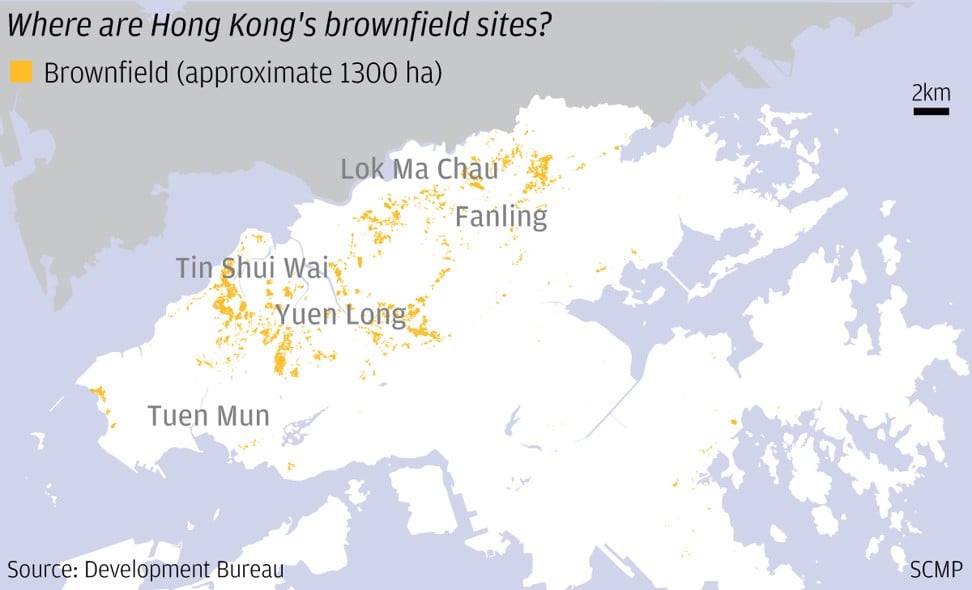

Releasing the development potential of some 1,300 hectares of brownfield sites in the New Territories, mostly privately owned agricultural land often rented to polluting businesses, is one of the 18 options. And it is one of four options that can yield results in 10 years.

“The studies will provide more information to the public on the option,” said Stanley Wong Yuen-fai, chairman of the government-appointed Task Force on Land Supply. The panel is charged with conducting and summarising the five-month consultation, which will end in September.

“It will make the debate more meaningful and focused.”

Wong said consolidating brownfield operations could provide better planning for such sites, which would enhance the surrounding environment.

A major difficulty in developing brownfield sites is relocating the businesses occupying them, such as those involved in container storage, heavy industrial-scale parking spaces, vehicle repairs, scrapyards and recycling workshops.

In mid-2016, the Civil Engineering and Development Department commissioned two feasibility studies on moving brownfield operations into industrial buildings. A 24-hectare site in the northern part of the proposed Hung Shui Kiu new town in Yuen Long and a 3.8-hectare site nearby were identified.

The studies addressed issues such as building design, environmental and financial assessments, and possible modes of operation and management.

Three development modes are likely to be proposed. One is to sell the sites to private developers via tenders to develop the dedicated buildings. The second is similar, but the government would set restrictions on land leases such as stipulating that certain spaces be rented to specific industries. And the third is that officials would pay for and develop the buildings.

The government should build these industrial buildings and rent spaces to us at reasonable prices

The government will consult stakeholders such as brownfield operator representatives and affected district councils.

Industry leaders believed the three modes would result in different rental rates, with spaces developed by the government being most affordable.

Stanley Chiang Chi-wai, chairman of the Lok Ma Chau China-Hong Kong Freight Association, said businesses had chosen brownfields for their operations because of the low rent.

As an example, he explained that rents for privately developed multi-storey logistics centres in Kwai Chung went for about HK$20 (US$2.50) per sq ft, while brownfield sites often charged less than HK$10 per sq ft.

“If the government ends up selling the sites to developers, it might as well not start the whole thing in the first place,” Chiang said. “The government should build these industrial buildings and rent spaces to us at reasonable prices, and operators affected by brownfield development plans should get the spaces first.”

But he acknowledged a public backlash could ensue against this model, as some would ask why public money should be spent to help the businesses.

Ho Chin-kong, 44, who works in Wang Toi Shan for a business offering parking spaces to construction site vehicles, thinks the answer is easy.

“Unless Hong Kong stops building altogether, there should be spaces to park large vehicles working in construction sites,” Ho said.

According to a study by land concern group Liber Research Community, there are some 70 hectares of brownfield sites in Wang Toi Shan, which is among 760 hectares not yet included in any official development plan.

Ho agreed the government should group similar businesses in a dedicated area. But he argued the area must be affordable. He said his employer had moved three times due to rent increases.

Industrial buildings would not be a solution for his sector, he added, asking: “How would any floor accommodate all these cranes?”

Yau Chi-wo, 54, who operates a car parts recycling yard, also in Wang Toi Shan, likewise believed an open-air area designated and managed by officials would be ideal for businesses like his. Yau said heavy vehicle parts bundled together would be difficult and costly to move up and down a building.

A Development Bureau spokeswoman said it had been separately exploring the possibility of suitable open-air sites for operations that could not practically move into buildings.

She added the government would formulate relocation measures based on “overall planning perspectives” of the different industries the brownfield businesses represented.

However, not every affected individual operator would receive a relocation arrangement, she said.

Liber’s Brian Wong Shiu-hung said he supported moving brownfield operations into buildings “in principle”. Yet he believed officials should not have kicked off the land supply consultation before the release of the studies.

Hong Kong rural body chief calls for calls for shift in land use policy to allow for more housing

A separate government study on where Hong Kong’s brownfields are and how they are used is expected to be completed towards the end of the year.

Wong believed these findings would be even more important, but the consultation might already be finished before that study concludes.

“Residents are asked to decide how Hong Kong should develop in the future, but they can’t even get this important information at such a critical time,” he said. “It makes people wonder whether the government really wants to handle brownfields at all.”